Today's GDP figures explained

GDP - 'Gross Domestic Product' - regularly finds its way into headlines. Economic and political fortunes can hinge on the decimals we see reported every three months and referred to all year round.

This morning, we were told that the economy grew in the last quarter by 0.7%, and grew by 1.9% over the course of 2013. That makes 2013 the best year since 2007 for growth.

So what exactly does it all mean?

Who knows?

Official GDP figures are always released by the Office for National Statistics (ONS), usually at 9:30am on the day of the release. However, some officials in government are given the figures 24 hours in advance. The thinking behind this is that it gives officials time to prepare responses and statements to go out shortly after the figures go public.

Most importantly, people with 'pre-release access' must not - by law - disclose either the numbers or hints as to what they show, until the figures go public via the ONS.

Last year, there were concerns over whether the Prime Minister hinted at the trend in GDP figures prior to their being made public.

This morning's Telegraph front page - printed hours in advance of the ONS's release of the figures - also might have given the impression that the official figures were being pre-empted:

"The economy is growing at the fastest pace since the financial crisis struck seven years ago, official figures will confirm today."

[Online] "Official figures to show UK economy grew by 1.9 per cent last year — the fastest pace since the financial crisis struck seven years ago."

There's no way the Telegraph should know for sure what the figures say in advance. It's probable the Telegraph were simply overstating what a number of commentators were already predicting but with an unwarranted degree of certainty (in fact, the paper predicted growth of 0.8%, a tenth of a percentage point above the official figure).

Banks and financial organisations regularly make predictions using their own models in advance of official figures. In fact many forecasters listed by the Treasury predicted the 1.9% annual rise two weeks ago. So it's not uncommon to see GDP predictions hitting the mark.

'Nowcasting'

The ONS measures GDP in three different ways, what's known as the output (what we produce), income (what we earn) and expenditure (what we spend) approaches.

But they don't measure all three at the same time. The quickest way is to measure output, which is done by sending out surveys to thousands of businesses who send back information about their turnover. From this, the ONS can make a 'preliminary' estimate for the whole economy about 25 days after the three-month period they're testing is over. That's what we see in releases like today's.

To an extent, this is 'nowcasting' (as the ONS themselves term it): an effort to get the best possible snapshot of the direction of travel for the economy by filling in the blanks for industries who haven't yet returned complete data with estimates.

For these reasons, the ONS needs to publish revisions to GDP on a regular basis. So along with preliminary estimates, there are second estimates, quarterly national accounts and the annual blue book, as well as occassional general changes, each of which uses progressively more data and better methods for estimating GDP, giving us a fuller and more accurate picture.

What you thought was true? Never really happened...

The obvious message to take away from this is that preliminary estimates are almost always revised later on as new information becomes available. And the data is there to prove it. Not counting the latest, there have been 83 quarters since the first three months of 1993. Of them, only six of the initial preliminary estimates still stand, and only 18 are still within 0.1%.

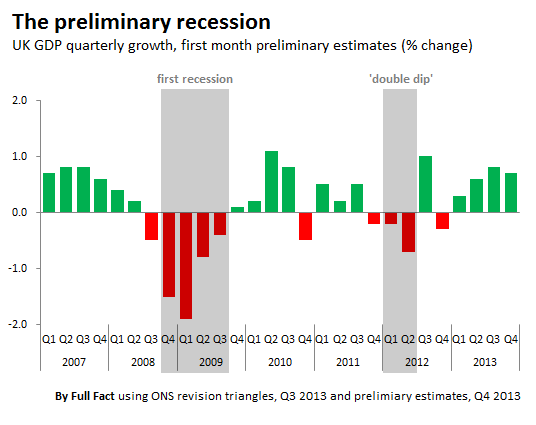

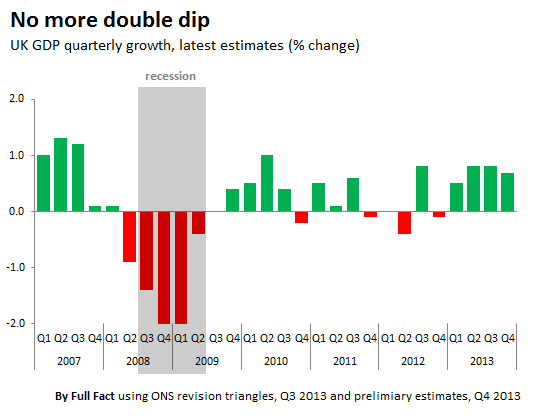

The most glaring recent example of this was the 'Double-dip recession' as it was called, when GDP was thought to have fallen for at least two successive quarters for the second time in recent history.

Except it didn't. As the ONS got more data and refined its calculations, it turned out the economy didn't dip as much as it had previously thought. The differences in economic terms were minor: 0.3% was the biggest revision of the year. In political terms, coming in at either side of the zero line can be huge.

Still, positive growth of 0.7% this month is almost certainly enough to be sure that the economy is at least growing - while preliminary estimates are often revised, they don't tend to be changed by more than a few tenths of a percentage point either way.

Even then, some have questioned the value of using GDP as the 'be all and end all' measure of the economy's health. There was a great deal of discussion last year after poor GDP figures jarred with good unemployment figures, suggesting that using the growth measure alone didn't give the full picture.

In addition, and as we've highlighted before, expectations can play as much a role in stimulating confidence as can actual hard figures coming out of ONS. The Office for Budget Responsibility's most recent predictions of how the economy is set to grow show how difficult it is to predict the future.

Correction (30 January 2013)

The original version of this article stated that preliminary estimates are almost always "wrong". This was changed to "revised later on" to better reflect the ONS's process of deriving GDP. These are always estimates and, although they do improve as more information becomes available, they can never guarantee complete accuracy.