How to spot misleading images online

This is an old version of our guide to spotting misleading images, which contains some out of date information. You can find our newer version here.

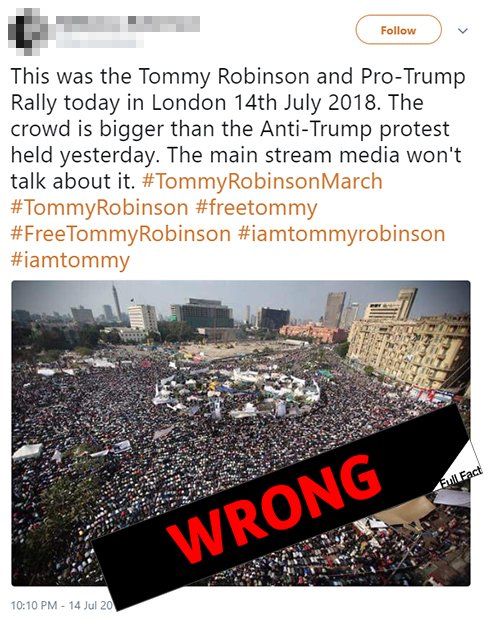

This image was shared over the weekend, claiming to show a rally in support of far-right activist Tommy Robinson and US President Donald Trump in London on Saturday 14 July. At the time of writing it had over 7,000 retweets.

It's actually an image of people praying in Tahrir Square in Cairo, Egypt. It was taken in November 2011.

It can be difficult to work out whether an image on the internet is genuinely what it claims to be, but there are some steps you can follow to spot misleading or doctored images online.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Use common sense

Common sense is your first line of defence. If you see an image online, especially one going viral, ask yourself if it makes sense. In the case of the supposed Robinson/Trump rally, there are a number of questions you might want to ask.

Firstly, does the context make sense, and does it fit with what you already know to be correct? In this case the context does make some sense—Donald Trump was in the UK that weekend, and there was a widely reported demonstration against him on the Friday night. There were also protests in support of Tommy Robinson, though these were reported to be a lot smaller.

If you are suspicious of the image, some other simple questions can help interrogate further. Do the details in the picture fit with the description? For example, are there any landmarks you could identify or recognise? London has an iconic skyline, yet there are no recognisable silhouettes in the background. You could also check if the weather in the picture matches up with other pictures or the forecast for that day.

You can also look at what’s going on in the image—the people in it are praying rather than protesting.

If the image has been shared on social media, it’s also worth looking at the comments under a post. If there is something wrong with the image, it’s possible that lots of other people have also expressed doubt, or even debunked it outright—as was the case with this tweet.

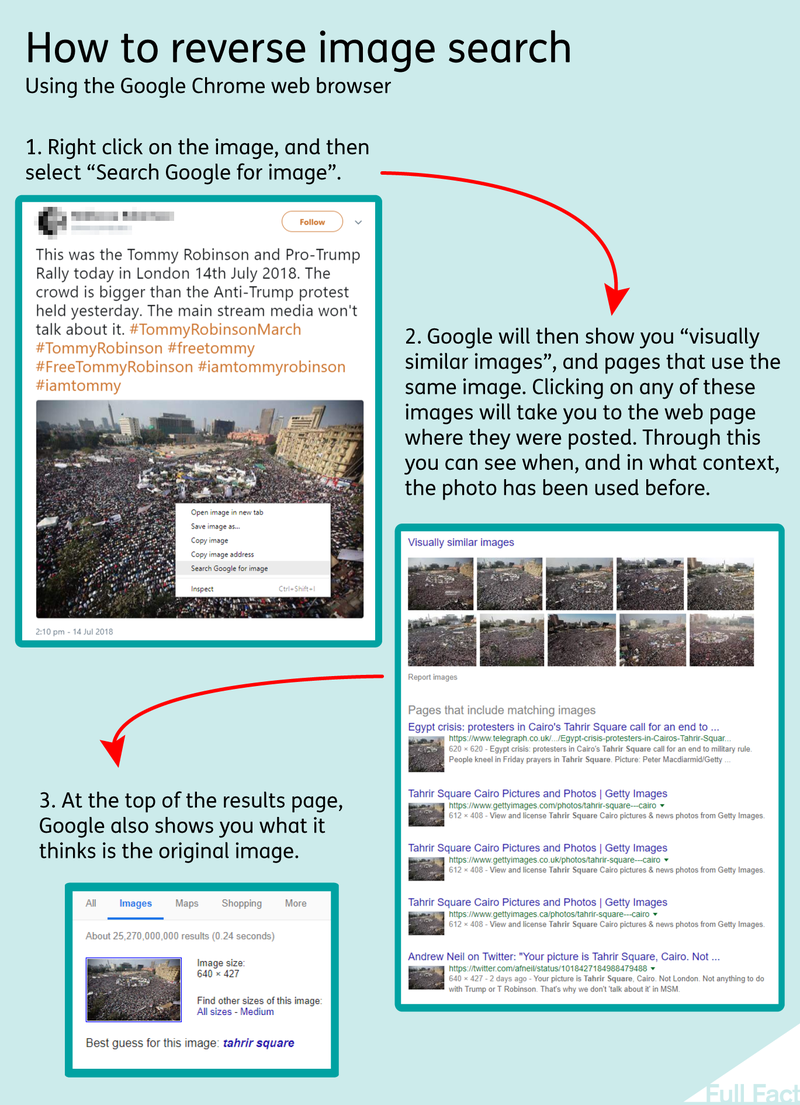

Reverse image searching

If you are suspicious, but still not certain that the image is misleading, one of the best options is to do a reverse image search. Using Google Chrome, if you right-click on the image and click “Search Google for image”, Google will tell you where it thinks the image is from.

Clicking on the image at the top of the search results also shows you where the exact image has been used before—in this case in Al Jazeera and NBC News articles about the Arab Spring from 2011. The image is dated as the 25 November 2011.

Another example of this is a satirical tweet from 2016, claiming to show a vast crowd at a Jeremy Corbyn rally in Liverpool. A reverse image search reveals it was actually Liverpool F.C.’s Champions League victory parade in 2005.

If you’re not using the Chrome browser, you can still do a reverse image search. Right-click on the image you want to search for and copy the image address/URL. Then go to http://images.google.com and click the camera icon in the search bar. Paste the image address into the search box under “Paste image URL” and then click “Search by image”.

You can also do reverse-image searches from the Google Chrome app on your mobile phone. Hold your finger on the image for a couple of seconds and then select the “Search Google for image” option. Searches can also be made using Bing, the dedicated reverse image search engine TinEye, or by installing a Google Chrome plug-in called RevEye, which allows you to reverse image search on five search engines in one go.

Image quality

Sometimes genuine images of an event can be doctored to show things that didn’t happen. Often with these images the key warning sign is not the dubious context of the image, but its poor quality.

Last weekend a doctored image of a pro-refugee protestor was shared by American actor James Woods, and Nigel Farage. Mr Farage removed his post after realising it was edited, but Mr Woods’ post is still online.

The slogan on the protestor’s placard has been edited, and there are some clear warning signs to suggest this. Firstly, the typeface of the words that have been added is very different to the original text—it’s much fuzzier and appears hand-drawn.

Secondly, the image’s low-resolution quality is a cause for doubt. German broadcaster Deutsche Welle points out that copied images are less sharp and of lower quality than originals.

A reverse image search confirms that this image has been doctored.

It’s also worth looking out for some of the typical mistakes you see in images that have been edited to show something they’re not. These include missing or inexplicable shadows, reflections in windows which don’t match up, or additional or missing limbs on people.

Familiar memes

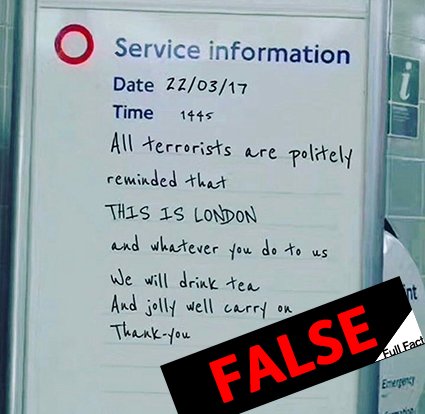

Messages on the London Underground are classics of the doctored image genre. After the Westminster terror attack last year, one MP shared an image of this message apparently written on a London Underground service information board. It was quoted by another MP in the House of Commons.

The key giveaway here is the handwriting—the letters are quite stylised, and remarkably consistent. A reverse image search shows links to a number of pages reporting that the image was created using an online generator.

The World Cup also saw an avalanche of memes around the theme of “football’s coming home”. So the image claiming to show that a government minister’s resignation letter spelled out “it’s coming home” should arouse immediate suspicion. It’s not genuine—but how can you confirm this?

In cases where a reverse image search won’t work, some other quite simple methods might. Firstly, always check the account sharing the image. In this case the account describes itself as “Fake news and comment”, which is a clear warning sign.

To be absolutely certain it’s not all it appears to be, you can try and find the image yourself. If it's a significant document, it’s highly likely that major news outlets will also be reporting on it. Googling “David Davis resignation letter” brings up a number of news outlets that reported the wording of his letter in full, alongside a photo of the original letter. Neither the text, nor the letter’s layout match up with the “it’s coming home” version, confirming that it is not genuine.

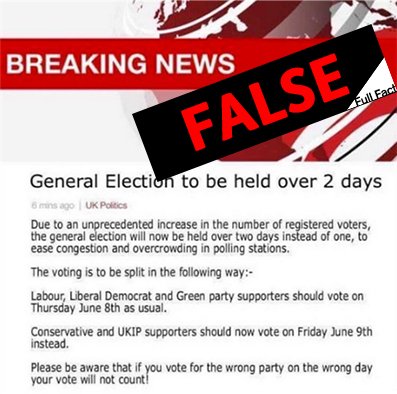

If an image contains a lot of text, you can also base your digging around that. The image below should trigger some suspicions given both the quite surprising news story, and low-resolution quality of the image.

Given that this looks like it’s from the BBC website, a BBC article should show up if you put the exact wording into google. Putting the text in “quotation marks” will only bring up pages where the wording matches exactly.

Searching for the wording of the first two lines of this article brings up only three results. That these three pages are also all meme websites confirms that it is not a real BBC news story.

Full Fact's aim is to improve the standards of public debate for everyone. Please support our work and become a regular donor today.