Are juries too stupid for justice?

"It's time they went the way of the ducking stool" cried Simon Jenkins in the Guardian. "Do we need IQ tests for juries?" asked Melanie Phillips in the Mail. "Jury collapse shows the failings in our education system" posited Iain Martin in the Telegraph.

The jury in the trial of Vicky Pryce - anonymous as they must remain - have certainly made their brief existence an illustrious one.

Earlier this week they failed to reach a verdict over whether the former wife of ex-MP Chris Huhne had been coerced into taking her then husband's speeding points. Following the trial's collapse, ten questions asked of the judge by the jury were published and widely circulated. Much derision ensued.

But what lessons can we really draw from a case such as this? Very few, said Professor Cheryl Thomas, quoted in the Guardian this morning. "More than 99% of the time juries reach a verdict. A hung jury is extremely rare".

Does she have a point? Let's take a look at some numbers.

Is what happened in the Vicky Pryce case normal?

When it comes to verdicts, official figures are elusive. Figures from the Ministry of Justice do tell us the number of defendants convicted after pleading not guilty on unanimous and majority decisions from the jury, but not how many were 'hung' and the jury discharged.

For the answers we need to look to a 2010 research paper commissioned by the Ministry of Justice and undertaken by Professor Thomas: Are Juries Fair? This compelling study used case simulations, data from the Crown Court Electronic Support System (CREST) and post-trial surveys of jurors, analysing data from 2006-2008.

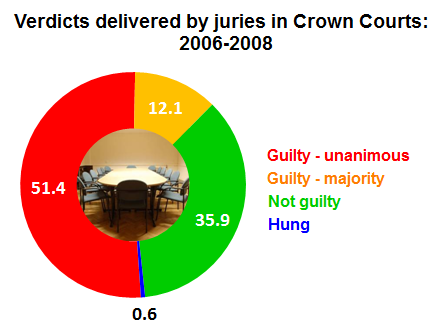

Sure enough, the study found that cases where the jury was hung and failed to reach a majority decision accounted for less than 1% of all jury verdicts in the two years:

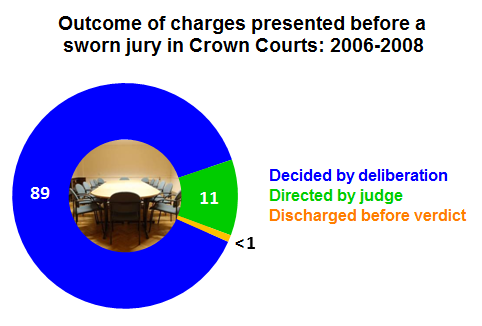

Furthermore, out of all cases that are heard by a jury, less than 1% of charges (not cases) resulted in the jury being discharged for whatever reason. Of the remainder, the vast majority are deliberated and decided upon by a jury, the rest being directed to them by a judge (this isn't binding and can't be a guilty verdict):

In other words, what happened in the Vicky Pryce trial this week was extremely unusual.

Do juries understand the rules?

The same Government research also examined how well juries comprehended the judicial directions given to them, coming up with some interesting findings. Using jurors who took part in the study's case simulations (in Nottingham, Winchester and Blackfriars), the researchers asked the participants what their understanding was, then tested this by asking them to recall key questions the judge had directed to them to aid their deliberations.

The researchers concluded that:

"Most jurors thought the judge's legal instructions were easy to understand, but a majority in fact did not completely understand them in the terms used by the judge in his instructions."

From this evidence, juries claim to understand instructions given to them more than they actually understand them in reality. Furthermore, the study positively suggested that a written summary of the legal directions given to jurors during the judge's oral directions improved the jurors' comprehension of the law.

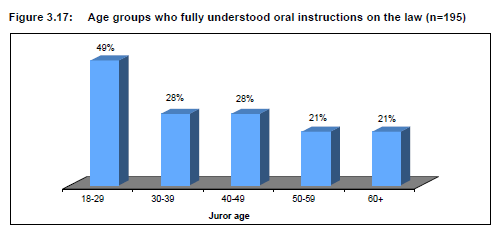

In addition, suggestions that the 'younger generation' have been educated badly and therefore don't understand the directions as well aren't borne out by the evidence. The research found that younger jurors comprehended legal directions better than older jurors:

There's not a great deal of evidence out there about juries' understanding of the law and how they come to reach decisions about cases, as the 2010 research itself admits. There's likely more still to be done, but for now the existing evidence suggests we shouldn't be reading very much into this case whatsoever.