Black people and criminal justice

“If you’re black, you’re treated more harshly by the criminal justice system than if you’re white.”

Theresa May, 13 July 2016

Black, Asian and minority ethnic people are over-represented in the criminal justice system in England and Wales. Whether black people are treated more ‘harshly’ than white people is a more complex topic, but there’s also some evidence to suggest this happens in parts of the system.

The evidence we’re looking at in this piece relates just to England and Wales, as there are separate systems and statistics in Scotland and Northern Ireland. Some of the evidence refers to all black and minority ethnic groups collectively, rather than black people alone.

It’s worth bearing in mind that most people say they are ‘confident’ that the criminal justice system is fair, but black and mixed ethnic groups are the least likely to say so.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

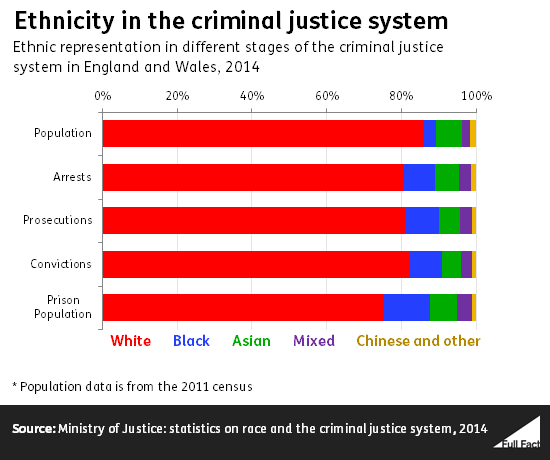

Black people are over-represented across different parts of the justice system

This is according to the Ministry of Justice’s own statistics on race in the justice system, and has previously been acknowledged by the government.

About 3% of the population of England and Wales self-identify as having black ethnicity, according to the 2011 census. But more than 3% of people arrested, prosecuted, convicted of a crime and in prison are black. The last case presents the biggest difference in proportion: 12% of prisoners in England and Wales have black ethnicity.

That’s because these numbers alone don’t tell us the reason for the over-representation. If, for example, one ethnic group only committed serious crimes and another committed only minor offences, we’d expect the first to be more likely to be in prison.

In that case the over-representation wouldn’t be because the system was treating them unfairly, it would be because of their behaviour—which in turn could have other explanations.

So the challenge for researchers is to dig deeper, and several studies already have.

Some evidence of racial bias in the system

A few years ago the government published research into whether a person’s ethnicity made them more likely to be sentenced to prison after being found guilty of a crime—as opposed to, say, community service. It looked at people who had committed the same type of crime in order to avoid skewing the results like in the example discussed above.

The study found there was a small but significant bias against black and minority ethnic people. It concluded:

“Black and minority ethnic offenders (particularly male offenders) were more likely to be sentenced to prison than White offenders (particularly White female offenders), under similar criminal circumstances.”

This still isn’t perfect proof. For instance, it can’t account for specific case-by-case circumstances that justify different sentences—what are called ‘aggravating’ and ‘mitigating’ factors.

Looking at how the police operate is also an important part of the equation, according to Patrick Williams, a lecturer in criminology at Manchester Metropolitan University.

We know, for instance, that black people are four and a half times more likely to be stopped and searched by the police than white people, compared to their shares of the population. Other non-white ethnic groups are also more likely, to smaller extents.

Mr Williams also says that in certain cases, black people are much more likely to be charged than cautioned for the same offence. Research has found that for cocaine possession, 78% of black people are charged rather than cautioned, compared to 44% of white people.

More evidence is on the way

Earlier this year, the Prime Minister asked David Lammy MP to lead a review into possible racial bias in the criminal justice system, which is expected to be published in 2017.

So there’s good reason to expect the picture to be much clearer then. But there are some concerns about the evidence that review will be considering.

Earlier this year the Bar Council and Criminal Bar Association expressed concerns that while the review was welcome, it needed to look at the criminal justice process as a whole rather than focusing on just certain parts.

For example, if black people are more likely to be prosecuted than white people, that could be because a disproportionate number of black people are being arrested in the first place.

The government’s call for evidence on the review has now closed.