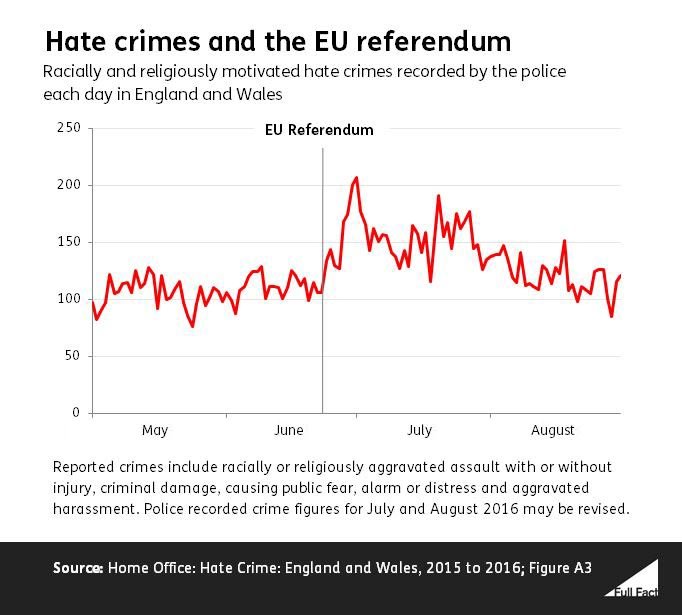

It’s correct that there was a “sharp increase” in the number of hate crimes being recorded in England and Wales, after the EU referendum.

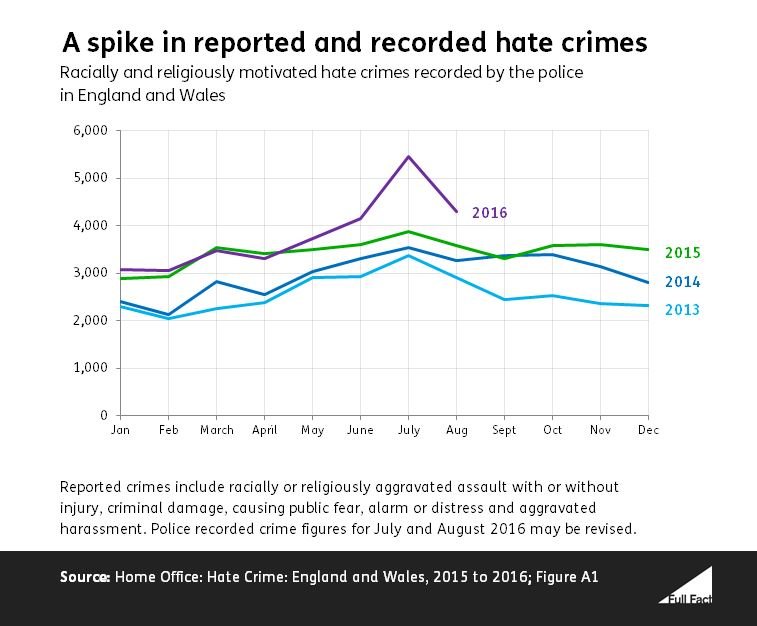

41% more hate crimes were recorded in July 2016 than in July 2015. That’s a big spike compared to previous figures.

Mike Hough from the Institute for Criminal Policy Research told us that the increase in the number of hate crimes being recorded probably did reflect a real change in the number of hate crimes being committed. Another likely factor was the police and victims being more aware of religious and racial hate as a possible motivation for crimes.

There's unlikely to be a definite answer on the relative importance of each factor.

A crime is recorded as a hate crime if the victim, or the person reporting it, thinks that it was at least partly motivated by the victim’s perceived race, religion, sexual orientation, disability, or because they were transgender. Comparing crime surveys with police reports suggests that there’s a gap between the number of hate crimes that people experience and the number that get reported to the police. It seems that most aren’t.

Numbers

More hate crimes are recorded in summer than in winter. So to get a good picture of how the numbers changed in July, it’s sensible to compare it with the same month in the previous year.

The number of racially or religiously aggravated offences recorded by the police in July 2016 was 41% higher than the number recorded in July 2015. That’s the biggest year-to-year increase in recorded hate crime for any month since January 2013.

On average the number of hate crimes recorded by the police rises from year to year. In the previous 12 months, the average year-to-year increase for individual months had only been about 7%.

Reasons

Comparing the number of hate crimes recorded by the police with the number reported in the crime survey suggests that hate crimes are underreported. An increase in the number of hate crimes reported by the police could be due to a combination of three things.

First, it might be because the actual number of hate crimes has increased.

Second, victims and witnesses might be more aware that crimes might be racially or religiously motivated and more confident in reporting that to the police. What gets recorded as a hate crime depends on how victims, witnesses, or the police perceive it.

Third, the police might be more sensitive to racial and religious motivation and record more crimes as hate crimes. Around the time of the referendum, an increase in the number of reported hate crimes meant that the Police Chief’s Council asked forces to send weekly rather than monthly reports.

There have been similar, although apparently smaller, rises in the number of hate crimes reported to the police after major news events in the past, such as the murder of Lee Rigby in July 2013, or Charlie Hebdo in January 2015.

Adding it up

So which reason is most important? Mike Hough from the Institute for Criminal Policy Research told us that,

“I think the safest conclusion is that:

- There must have been a real spike in hate crimes

- Once this attracted media attention, victims were more sensitised to the phenomenon and thus more likely to report, and

- The police, similarly sensitised, became more likely to record reported incidents – and to flag them as hate crimes.”

He said that he didn’t know of any research that could put a number on the relative importance of each effect. So, in the end, it seems to be a matter of judgement.