Police treat home secretary speech as 'hate incident'

BBC News, 12 January 2017

Reports that a speech on immigration by Home Secretary Amber Rudd has been treated by police as a ‘hate incident’ have turned heads today.

In the speech, which sharply divided opinion, Ms Rudd set out proposals to tighten the tests companies have to take before recruiting workers from overseas.

Readers of our coverage on measuring crime will be no strangers to the difference between ‘incidents’ and ‘crimes’, and it’s worth spelling out the distinction in the light of this case.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Not all ‘incidents’ are ‘crimes’

Imagine that a man on a ladder is breaking into a house and someone reports it to the police. The person who reports it says they’ve seen a burglar. But when the police turn up, it turns out he’s the owner and he forgot his keys. An incident has occurred, but a crime hasn’t.

As West Midlands Police has confirmed, it doesn’t consider Amber Rudd’s speech a hate crime. It’s been logged as a ‘non-crime hate incident’, and isn’t being taken further by the force.

That terminology might make it sound like the police agree the content of the speech was hateful, but that isn’t true.

According to the police’s own rules that they get from the Home Office: “all reports of incidents, whether from victims, witnesses or third parties and whether crime related or not, will, unless immediately recorded as a crime, result in the registration of an auditable incident report by the police.”

In other words, someone reported Ms Rudd’s speech to the police, claiming it was using hate speech. The police were obliged to record that as an incident, whether or not they eventually ‘upgrade’ it to a crime.

As we’ve said before, crimes are recorded as ‘hate crimes’ if the victim, or the person reporting it, thinks that it was at least partly motivated by the victim’s perceived race, religion, sexual orientation, disability, or because they were transgender.

When incidents become crimes

The same rules from the police state that for incidents to be ‘upgraded’ to be called crimes, the “balance of probability” must show that:

- The circumstances of the victim’s report amount to a crime defined by law (the police will determine this, based on their knowledge of the law and counting rules); and

- There is no credible evidence to the contrary immediately available.

This test can differ for certain kinds of crime, such as those against the state, and it goes on to say that the victim believing that a crime has occurred is usually sufficient to justify recording it as such.

Crimes don’t necessarily remain crimes. If more information comes to light and the police decide that the test is no longer being met, the cases are ‘no-crimed’.

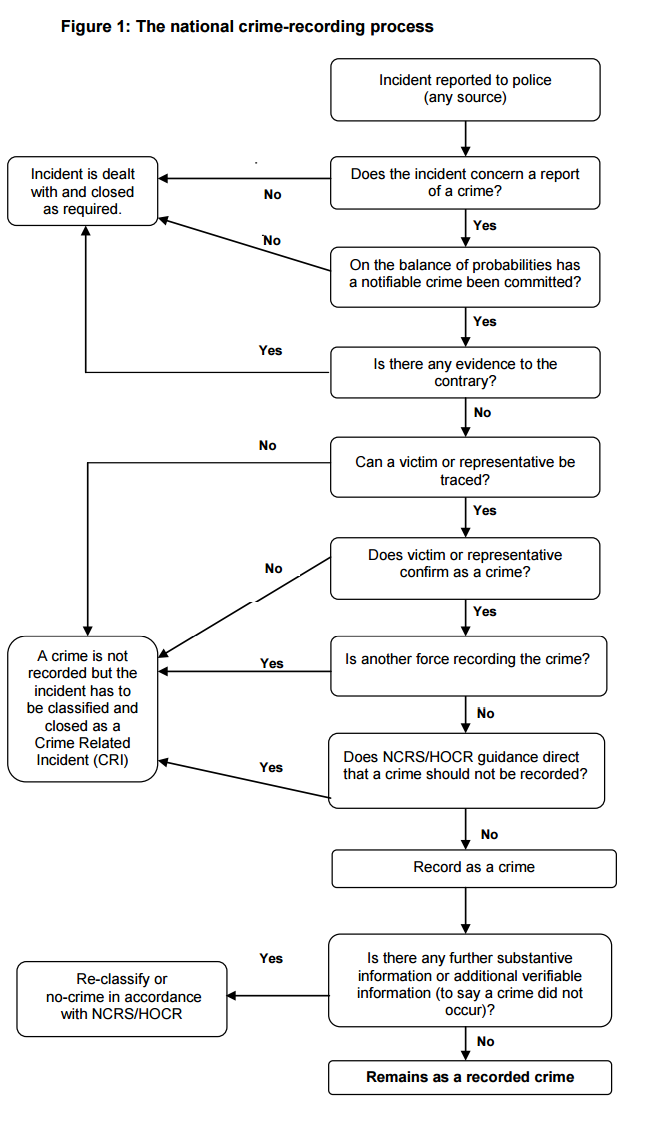

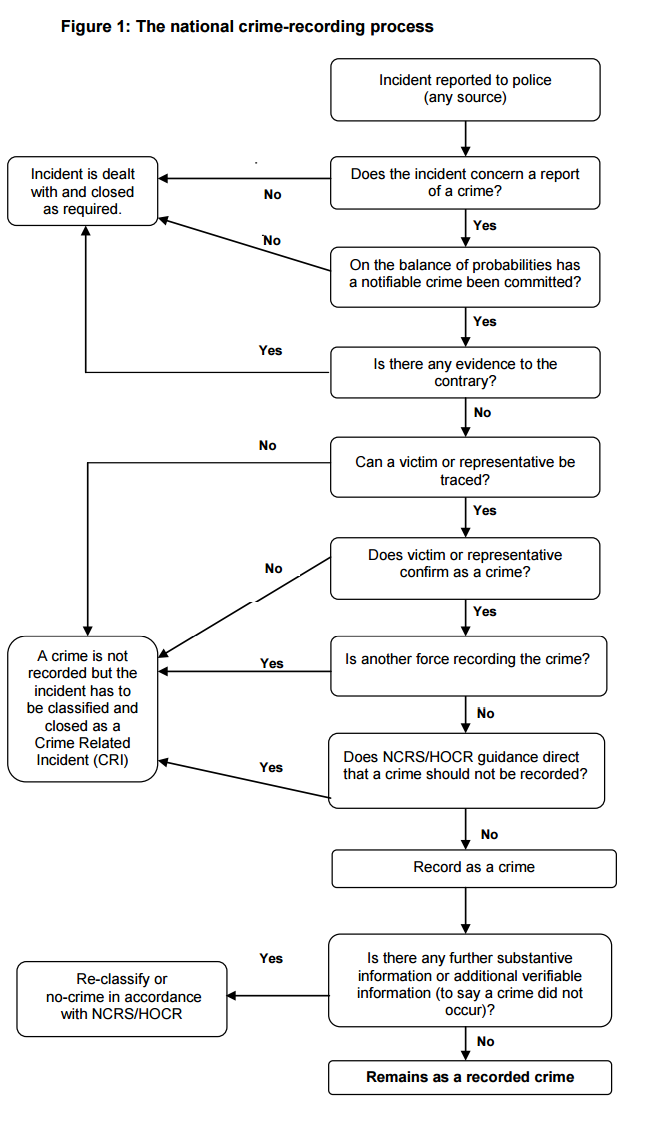

If you want to put yourself in the police’s shoes, here’s how HM Inspectorate of Constabulary summarises the process: