The state of prisons in England and Wales

Around 85,000 people are in prisons in England and Wales.

The prison population peaked at 88,000 in 2011, partly explained by the riots that summer, before falling to 84,000 at the end of 2012.

The total population of the UK has also increased over time. There were 182 prisoners per 100,000 adults in England and Wales in 2016. This is higher than historic levels back to 1901, apart from the peak in 2011, according to the House of Commons Library.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Space in prisons

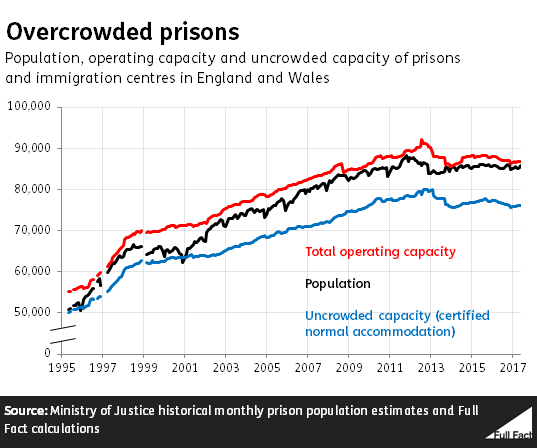

The total number of prisoners that the Ministry of Justice says it can hold “without serious risk”—the operational capacity—has increased broadly with the number of prisoners.

However, the uncrowded capacity which represents “the good, decent standard” accommodation the service aims for has been lower than the prison population for almost all of the past 20 years.

A quarter of prisoners are held in crowded accommodation according to official figures.

Staff

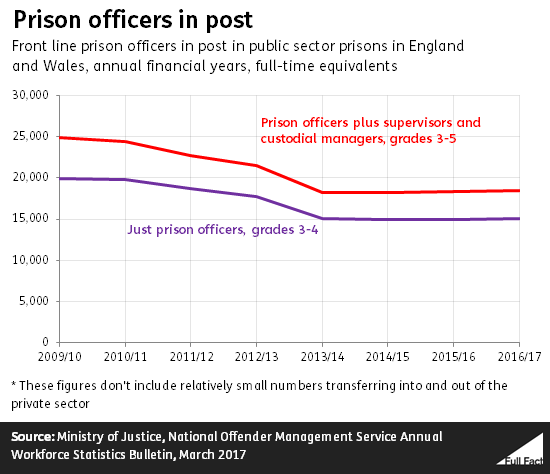

Around 24,000 people work in operational roles in the prison service. 10,800 more work in non-operational roles, like management, administration and services.

The number of staff in both areas has fallen since 2010, our earliest data. In March 2017 there were 30% fewer operational staff, and 29% fewer non-operational staff, than there were in March 2010. The fall in the number of non-operational staff is partly due to jobs being transferred to other organisations.

Over the last 12 months the number of operational staff has fallen by 168. This is largely due to falling numbers of operational support staff and supervising officers, which outweighs the increase in prison officers. The number of non-operational staff has increased by 248, driven by 155 more managers.

There are 15,000 ‘front-line’ prison officers working at band 3 or 4, who are not in management or supporting roles. That number is down from 20,000 in 2010, measuring by ‘full-time equivalents’ rather than headcount in all cases.

We’ve looked at these figures in more detail in a previous factcheck.

More frontline officers left than were recruited or promoted every year until 2015. Although this changed in 2015 (with 507 net new officers) the total number of full-time equivalent frontline officers first increased in 2016.

In 2017 there was a net gain of 711 front-line officers through recruitment and promotion, which translated into an increase of 122 full-time equivalents.

The government announced in November 2016 that it plans to recruit 2,500 new frontline officers by 2018.

Deaths

The number of deaths in custody fell slightly for the first time since 2013 this year, but remain at historically high levels. Other measures of violence have reached record highs.

The statistics cover the 12 months to June 2017 (deaths) or the 12 months to March (other measures).

Last year 316 people died in prison, a 2% decrease compared to 2016. 97 of these deaths were self-inflicted (the prison service doesn’t assume intention). For every 1,000 prisoners 1.1 ended their own life. An unusually high number of deaths have not yet been classified, so the current figures aren’t yet directly comparable to previous years.

Self-harming

The number of self-harm incidents increased by 17% in the last year, and the number of people self-harming by 10%. There were 40,000 incidents of self-harm. This is the highest on record. For every 1,000 prisoners, 129 self-harmed. In the same period to 2016 it had been 117 per 1,000, an increase from 97 per 1,000 in 2015.

Violence

Assaults on other prisoners and staff are the highest on record. There were 227 ‘prisoner on prisoner’ assault incidents per 1,000 prisoners, an increase of 16% since last year. Assaults on prison staff increased by 32%, to a rate of 84 incidents per 1,000 prisoners.

Incidents

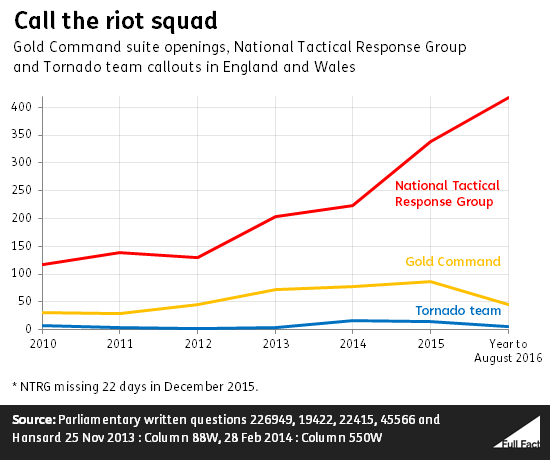

Specialist staff have been called to an increasing number of incidents since 2010.

The number of times the National Tactical Response Group has been called to prisons has been increasing. It was called over 300 times in 2015, compared to over 100 times in 2010.

The NTRG is a specialist team who are called to prisons to deal with potentially serious incidents. These include ‘incidents at height’ (often where prisoners have climbed onto safety netting), hostage-taking, and where two or more prisoners are disobeying instructions. The overwhelming majority of incidents are non-violent, and the team is sometimes called out as a precaution with ordinary prison officers able to deal with the situation themselves, according to the Ministry of Justice.

The Gold Command Suite is opened to deal with similar potentially serious incidents, as well as barricades, industrial action and other disturbances. It directs NTRG and Tornado teams to prisons. Its use has increased every year since 2011. In 2015, Gold Command was used 86 times compared with 30 times in 2010, and 46 times up to August 2016.

Tornado teams are prison officers with advanced training in “control and restraint techniques”. They were used to regain control during the HMP Birmingham riot in December 2016, for example. Tornado teams were called 15 times in 2015, compared to 7 times in 2010.

Most prisons have a target for the number of Tornado trained staff. 63% of prisons met or bettered their target in 2015/16. In January the government said it would increase the number of these staff.

The House of Commons Library has published a report about recent concerns over prison safety, examining possible causes of the increasing violence.

HM Inspectorate of Prisons has focused on the subject in its last two annual reports, saying safety outcomes from its assessments were worse than any time between 2007 and 2014.

The government put out a White Paper, Prison Safety and Reform, in November 2016, promising to “address the current level of violence and safety issues in our prisons”.

Get the detail

You can find out more about the state of prisons using our Finder tool. In summary:

- Offender management statistics—population, receptions and releases from prisons

- Prison performance statistics—prison-by-prison population, cost of places, overcrowding, drug use, escapes and absconds

- Safety in custody statistics—deaths, self-harm and assaults in prisons

- Proven reoffending statistics—figures on reoffending up to 2014

- HM Inspectorate of Prisons—independent inspection reports of prisons and parts of the prison system