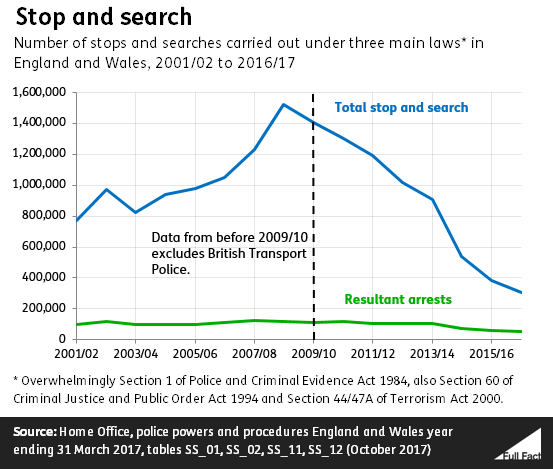

17% of stop and searches in England and Wales resulted in arrests in 2016/17, compared to 8% in 2009/10. There were over 300,000 stop and searches in 2016/17, compared to 1.4 million in 2009/10—meaning the overall number of stop and searches fell by 78%.

While it's tempting to take the higher arrest rate as an indicator of success, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services (HMICFRS) note that an arrest isn't necessarily a success, nor is a failure to uncover any wrongdoing necessarily a failure.

Offenders could, for instance, be arrested even if they're found to be empty of stolen or prohibited goods because they might react violently to officers or be wanted for another offence. On the flipside, failing to uncover wrongdoing could be regarded as a success if, without the stop and search powers in place, the person under suspicion would otherwise have been arrested unnecessarily.

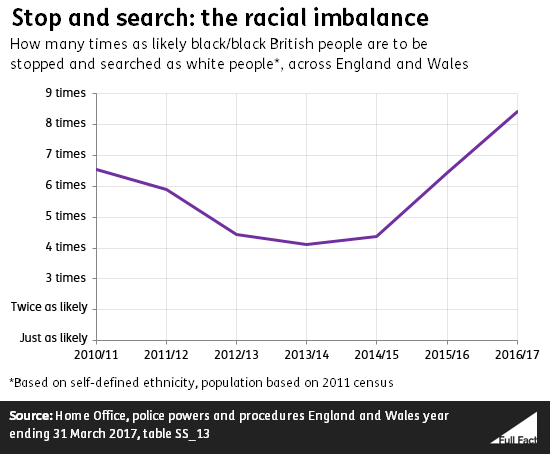

HMICFRS also reports that “While stop and searches on white people have decreased by 78 percent, stop and searches on people from BAME communities decreased by 69 percent. The decrease for black people was even lower, at 66 percent.” This is based on stop and searches under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act, which make up the vast majority of stop and searches.

People who self-define as black or black British are the most likely to be stop and searched of any ethnic group—it’s estimated at around 29 per 1,000 in 2016/17. They’re over eight times more likely to be stopped and searched than white people, and that ratio has been rising in recent years.

HMICFRS said in December 2017 that the rising ethnic disparity in stop and search frequency “has the potential to erode public trust and confidence in the police, particularly amongst black people, despite the reductions in the use of stop and search powers”.