Stop and search in England and Wales

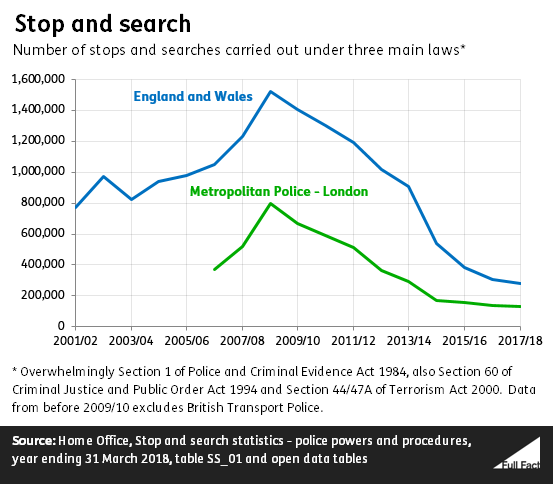

The use of stops and searches has fallen both in London and across England and Wales, following policy changes a few years ago.

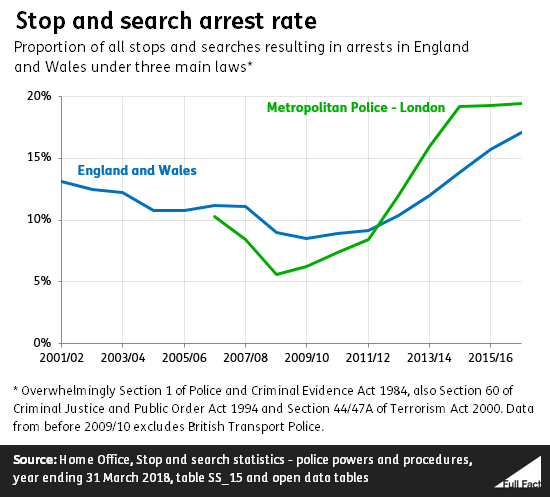

Stops and searches are more likely than ever to result in arrest.

Around 17% of searches resulted in arrests, with 13% resulting in another kind of action in England and Wales in 2017/18.

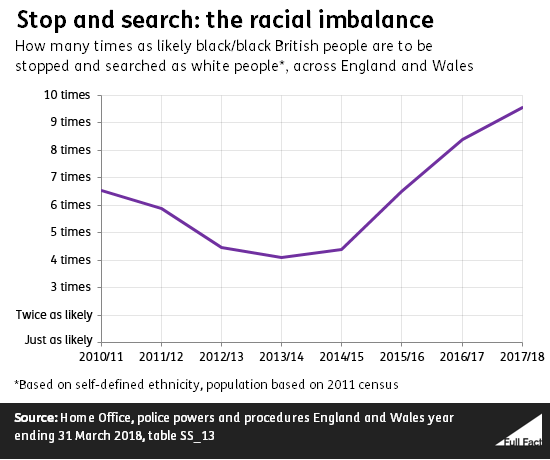

Black people remain much more likely to be stopped and searched than white people, and this gap has widened in the most recent year we have figures for.

The laws in Scotland and Northern Ireland are different, and they publish their own statistics.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

The rules on stop and search have changed

Almost all stops and searches take place under section 1 of the Police and Criminal Evidence Act 1984 and laws associated with that. It’s used by police to search people for things like drugs, weapons and stolen property, provided the officer has a reasonable cause to suspect they will find something. The use of section 1 searches had been declining rapidly in the last few years, but fell less sharply this year.

Stops and searches can take place under different laws as well. Those had also been falling rapidly due to changes in policy since 2012 to increase ‘fair use’ of the powers by the Home Office and Metropolitan Police.

In 2017/18 however the number of stop and searches carried out under section 60 of the Criminal Justice and Public Order Act increased from 630 to 2,500. Under section 60 a senior police officer can authorise searches for weapons without need for reasonable suspicion in a defined area, to prevent serious violence or to find weapons after an incident. 73% of section 60 searches in England and Wales were carried out by the Metropolitan Police.

For the first time since 2011 stop and searches were also carried out under section 47a (previously s.44) of the Terrorism Act 2000. The majority of these searches (145 of 149) were carried out by the British Transport Police.

In 2014 the government introduced the ‘Best use of stop and search’ scheme which aims to increase transparency in the use of stop and search and encourage forces to use the powers more effectively. All forces in England and Wales have now signed up and provide more statistics on the outcome of searches.

The use of stop and search has fallen

The use of stop and search in England and Wales peaked in 2008/09 when over 1.5 million were carried out. It has declined in every year since then. Since 2011/12—just before the police changes were brought in—stops and searches have fallen by over three-quarters.

The latest figures put them at just over 280,000 in 2017/18.

London has seen the same pattern. Stops and searches peaked in 2008/09 at nearly 800,000 and fell to just over 130,000 in 2017/18.

The number of stop and searches per person is much higher in London than in the rest of England and Wales, even once you factor in the roughly 2 million people who commute to London during the week.

Stops and searches are more likely than ever to result in an arrest

Only 9% of stops and searches resulted in an arrest at the peak of its use in 2008/9. That proportion has increased in the years since and was 17% in 2017/18.

Arrests are more likely in London—with 19% of Metropolitan Police searches resulting in arrest in the same year. The most recent figures suggest the arrest rate may be falling.

While it's tempting to take the higher arrest rate as an indicator of success, Her Majesty’s Inspectorate of Constabulary and Fire & Rescue Services note that an arrest isn't necessarily a success, nor is a failure to uncover any wrongdoing necessarily a failure.

Offenders could, for instance, be arrested even if no stolen or prohibited goods are found, because they might react violently to officers or be wanted for another offence. On the flipside, failing to uncover wrongdoing could be regarded as a success if, without the stop and search powers in place, the person under suspicion would otherwise have been arrested unnecessarily.

A third of stops and searches uncover something relevant

These are called “positive outcome” searches—which refers to any case where action is taken against people who’ve been stopped and searched. This includes arrest cases but also covers other resolutions like warnings and Penalty Notices. All cases where there isn’t a positive outcome are called “No Further Actions”.

Across England and Wales 30% of stops and searches had a positive outcome in 2017/18.

This figure could be higher in reality because some No Further Action cases do involve detentions under the Mental Health Act or informal advice being given when an officer has found something untoward.

The figures are similar for the Metropolitan Police in London. In 2017/18 60% of stop and searches resulting in a “positive outcome” were related to drugs offences, 11% to theft, fraud and counterfeit offences, and 9% were for “weapons, points and blades”.

Outside the Metropolitan Police, police officers find what they’re searching for in one out of five cases

Police forces have to report whether the outcome was linked to the reason for the search.

For example, when someone is stopped for a drug search and given a cannabis warning the outcome is linked. If no drugs are found but they’re arrested for carrying a weapon the outcome isn’t linked. If nothing is found and no action is taken that also isn’t counted as linked.

So in England and Wales, officers found what they were searching for in around one in five searches. The reason for the search makes a big difference, with searches for drugs being more successful than stops for weapon searches or going equipped.

They also find that whether someone is white or not makes little difference—the rate is still about 20%.

Again, these cover ‘positive outcomes’ of stops and searches, but they’re different to the figures mentioned in the previous section because they only include cases where the officer found what they were searching for in the first place.

Black people are still more likely to be stopped and searched

The majority of the population is white and the majority of stops and searches involve white people. Per person, black people are more likely to be stopped and searched.

Black people are about nearly ten times as likely to be stopped and searched as white people. Three in every 1,000 white people were stopped and searched in 2017/18, compared to 29 in every 1,000 black people.

The difference in rates between white and black people has grown since last year. Stops and searches have fallen in the last year overall but those involving white people have fallen faster than those involving black people.

Black people are more likely to be arrested following a stop and search. 21% of stops and searches on black people resulted in an arrest in 2017/18, compared to 16% of those conducted on white people.

We have more figures just for the Metropolitan Police in London covering June 2018 to May 2019.

Black people were four times as likely to be stopped and searched in London as white people—they were stopped 63.4 times per 1,000 people compared to 14.7 times for white people.

People of all ethnicities are more likely to be stopped and searched in London than elsewhere.

Positive outcome rates are similar whatever people’s ethnicity is. Around 25% of searches result in some action being taken.

Does stop and search work?

There is little research on whether stop and search prevents and deters crime.

Recent research using ten years of data from the Metropolitan Police found that:

“higher rates of stop and search (under any power) were associated with very slightly lower than expected rates of crime in the following week or month” …

“The inconsistent nature and weakness of these associations, however, provide only limited evidence of stop and search having acted as a deterrent at a borough level. It is possible that stop and search may be more strongly associated with crime at a more local level, assuming it is targeted appropriately in crime hot spots.”

It also found that increasing the use of section 60 powers (stops without reasonable suspicion) did not appear to affect violent crime.

Previous research on the use of section 60 powers to reduce knife crime also found no effect. Some US research has found small effects on some types of crime, and there is evidence that concentrating policing on crime ‘hotspots’ does deter criminals.