Throwing caution to the wind? The impact police cautions have had on the justice system

"Serious and repeat criminals should not expect to escape with a caution."

"Serious and repeat criminals should not expect to escape with a caution."

Those were the words of Secretary of State for Justice Chris Grayling this morning as the Government launched a review into the use of cautions in the criminal justice system.

The story made it into several headlines today, and brings back memories of the outrage expressed in the past at the numbers of violent criminals being let off with cautions rather than being convicted in a court of law.

So can we expect a change after the review?

It's worth summarising what we know already. The Ministry of Justice define situations where cautions are used:

"A caution can be administered when there is sufficient evidence for a conviction and it is not considered to be in the public interest to institute criminal proceedings. Additionally, an offender must admit guilt and consent to a caution in order for one to be administered."

Why give out a caution? Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Constabulary (HMIC) promote their use as a tool which provides "simple, swift and proportionate responses to low-risk offending" and furthermore to cut down the amount of time courts spend listening to cases and the amount of time police officers spend off the frontline.

HMIC supports its case with facts. Its joint study with Her Majesty's Crown Prosecution Service Inspectorate in 2011 on the use of cautions and other "out-of-court disposals" found that (across five police forces) cautions took up less police time than charging offenders, but more time than issuing Penalty Notice Disorders (PNDs) or restorative justice measures.

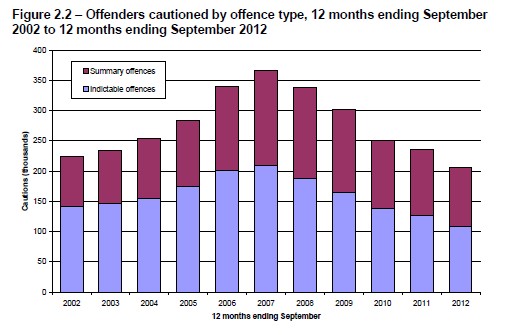

The latest statistics from the Ministry of Justice show that the number of cautions issued is actually decreasing, down from a peak of 367,000 issued in the year to Spetember 2007 to 206,000 in the year to September 2012:

The graph shows a noticeable trend - cautions increased yearly from 2002 to 2007 and have been declining since. This can be explained, to an extent, by the previous Labour Government's policy changes. In 2002, the Government introduced a target to narrow the 'justice gap' - the difference between the number of offences recorded and the number of offences brought to justice (when an offender has been cautioned, convicted or had the offence taken into consideration by a court"). The Government stated at the time that its objective was to:

"Improve the delivery of justice by increasing the number of crimes for which an offender is brought to justice to 1.2 million by 2005-06." [This target was actually met earlier than expected, and was therefore revised.]

This can to some extent explain the increased use of out-of-court disposals in the run up to 2007. In 2008, the target was changed to place more emphasis on bringing "serious crime" to justice, and by May 2010 this target was removed altogether. The Centre for Crime and Justice's analysis of the drop after 2007 came to a pithy conclusion:

"All the evidence pointed to the fact that the police were no longer earning Home Office brownie points for criminalising children and young people, not that there was any change in youth behaviour."

So why do we need a change?

In light of today's news, readers may well ask why a 'review' of the use of cautions is needed if the use of cautions is on the wane.

One reason is that there's concern that cautions are used inconsistently across different police forces and for different crimes. The Magistrates' Association, quoted in papers today, has been making this point for some time, stating in 2009:

?…the growth of out-of-court disposals is failing the public and "dumbing down" the criminal justice system…[the police] cannot be relied upon to handle them appropriately…there is inconsistency of their use, there is inappropriate use…?

Indeed, HMIC found in their 2011 study a large variation in the proportion of offences resolved through out-of-court disposals across police forces, ranging from 26% of all offences in West Yorkshire to 49% in Gwent.

The main concern, however, is that cautions are being over-used for serious offences such as violence against the person.

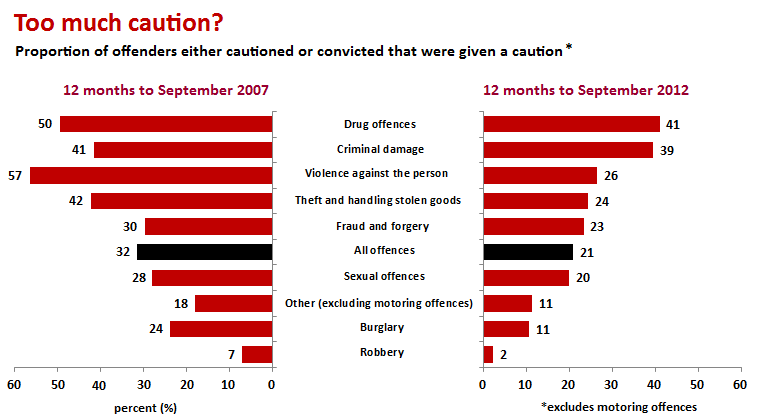

21% - or one in five - of all offenders either cautioned or convicted (excluding motoring offenders, mostly dealt with by Magistrates' Courts) are cautioned. But this varies by offence, from 41% of drug offences to just 2% of robbery offences. Offences such as violence against the person cause the most concern - 27% of these offences are dealt with by a caution as opposed to a conviction.

How appropriate the use of cautions for certain offences as opposed to others is a matter for debate rather than hard facts. However given the criticisms levelled against the previous Labour Government's experience of using targets to close the justice gap, any administration which wants to adjust the levers of the justice system through new guidelines might wish to exercise caution before proceeding.