11 February's BBC Question Time, factchecked

On the Question Time panel last night were Conservative Stephen Crabb, Labour's Carwyn Jones; UKIP's Nigel Farage, Plaid Cymru's Leanne Wood, and the comedian Romesh Ranganathan.

We've checked their claims on the Welsh NHS, junior doctors and the effect of immigration on wages.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Cancer patients in Wales

“You’ve got 50,000 Welsh patients, who because your cancer care provisions are so poor, actually went to England.”—Nigel Farage

“You've made that figure up quite frankly, unless you can tell me where it's from.”—Carwyn Jones

We can tell Carwyn Jones where the 50,000 figure is from, although there isn’t any evidence that these are people who went to England specifically due to poor care in Wales.

Welsh residents were admitted to English hospitals on 56,000 occasions in 2014/15, according to statistics from the Welsh government. UKIP told us it was using the same set of figures but for 2012/13, when the equivalent number was at about 51,000.

This is the number of admissions, not patients—some patients will have been admitted more than once.

Most were not cancer patients—in 2012/13 about 2,000 Welsh residents were admitted to English hospitals, accounting for about 7,000 admissions that year.

We don’t know why they went to England.

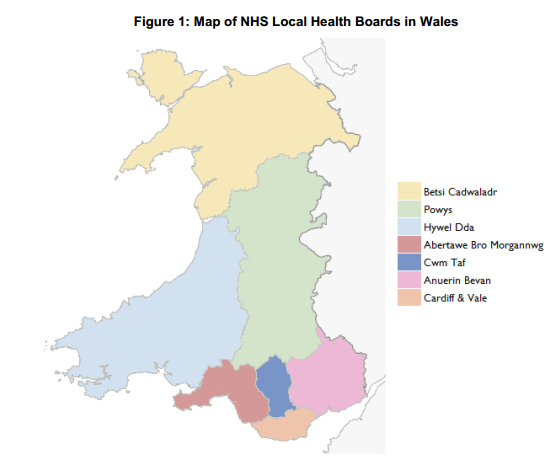

The great majority of the admissions were of people from two areas of Wales, both of which share an extensive border with England. Patients from the Betsi Cadwaladr University and Powys Teaching health boards made up 87% of the cross-border admissions.

Last year Parliament’s Welsh Affairs Committee concluded that:

Last year Parliament’s Welsh Affairs Committee concluded that:

“Cross-border movements have been a fact of life for many years, and this is no less the case for health services. For those residing in immediate border areas, the nearest health provider may not be in their country of residence. There is no practical or realistic prospect of diverting these well-established cross-border flows, nor would it be desirable to do so.”

The Welsh NHS

“On every measure on waiting times and healthcare provision Wales is the failing part of the National Health Service in the whole United Kingdom”—Nigel Farage

There are a multitude of measures that can be used to compare the four countries of the United Kingdom, but on the whole it’s too simplistic to use these to say any one country is ‘failing’.

The Welsh NHS does perform more poorly than the English NHS on waiting time targets for things like the length of waits in A&E and for planned procedures, according to analysis by health think tank the Nuffield Trust last year. It isn’t behind for all waiting times though—the Nuffield Trust found waiting times for people referred by their GPs for cancer treatment were a little better in Wales.

And as the Nuffield Trust wrote last year:

“It is too simplistic to draw conclusions based on these narrow measures that the Welsh NHS is significantly worse than its English counterpart. These measures don't tell us much about the quality or safety of care received or the experiences of patients.”

In a report published this morning the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said:

“From the limited country-specific data available, no consistent picture emerges of one of the United Kingdom’s four health systems performing better than another.”

Doctors in Wales

“Romania, Poland and Slovenia are the three countries that have fewer doctors per head of the population than we do here in Wales.”—Leanne Wood

This seems about right, based on figures produced by Plaid Cymru last year. We’ve asked it for more details.

The party calculated that there were 2.7 doctors in Wales for every 1,000 people, according to its calculations.

That’s fewer doctors per person than in other EU countries, according to OECD data from the last few years, other than in Slovenia (2.6), Romania (2.5), and Poland (2.2).

The UK had 2.8 doctors per 1,000 people in 2013.

As with a lot of international data there can be some issues with making comparisons like these. The countries differ in whether they count doctors in training, for instance.

Junior doctors

“[Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt] has at best been disingenuous because as Mr Farage pointed out, there is an increased mortality at weekends but there is nothing that has been suggested or proven to show that is related to any lack of junior doctors at that time. It is multifactorial.”—Audience member

Several academic studies have found that people admitted to hospital at the weekends have an increased risk of death in the following thirty days. The audience member is right to say the studies didn’t attempt to explain why this was the case.

Some of the increased mortality might be due to the type of patient who is admitted at the weekend, and while the various research projects have tried to account for that, critics have argued it's not possible to control for everything.

The most recent report said:

"It is not possible to ascertain the extent to which these excess deaths may be preventable; to assume that they are avoidable would be rash and misleading".

Even if the deaths were shown to be avoidable, that wouldn’t necessarily mean they were due to a shortage of junior doctors. For instance it could be about other types of staff like consultants or nurses, or the availability of tests that mean patients are diagnosed quickly. Or it could be due to differences in services across the much wider health and social care system.

The effect of immigration on wages

“Is that a boost for British workers? Is getting rid of British workers and replacing them with foreign workers or driving down the wages of existing workers… is it good for British workers and families?”—Nigel Farage

Research suggests that immigration has a small impact on the average wages of existing workers, according to the Migration Observatory. In particular, low-wage workers lose out while medium and high-paid workers gain.

It said the wage effects were likely to be greatest for immigrants already living and working here.

Immigration from outside the EU can have a negative impact on the employment of UK-born workers, especially during an economic downturn. But overall, immigration has not been found to have a significant impact on unemployment. The impact will differ depending on when people have arrived, where they’ve come from and the skills they bring.

In the long term, any immediate fall in wages and employment of UK born workers could be offset by rising wages and employment, according to the Migration Observatory.