In her recent speech on exiting the EU, Theresa May said that if the UK failed to strike a favourable new trade deal with Europe, then among other things:

“...we would have the freedom to set the competitive tax rates and embrace the policies that would attract the world’s best companies and biggest investors to Britain.”

In other words, if the UK fails to strike a favourable trade deal, it always has the option of reducing corporation tax and drawing multinational investment and tax revenue away from its European neighbours.

Emily Thornberry made a reference to this on last night’s Question Time:

“If we leave the European Union in the way Theresa May is saying that we might have to, she's going to cut corporation tax, I think it's 120 billion over five years.”

Emily Thornberry, BBC Question Time, 19 January 2017

These figures are estimates from the Labour party, and Ms Thornberry has quoted them incorrectly. The £120 billion includes estimated money lost to tax reductions that have already happened or are already planned, not just the ones the Prime Minister is suggesting in her speech.

The Labour Party has estimated the direct effect of cutting corporation tax to the same rate as Ireland would build up to a £63 billion loss in tax revenue over the next five years. Ireland has the lowest tax rates in the OECD, an organisation of rich countries.

In other words, Labour estimates that the direct costs of carrying out Theresa May’s suggestion are about half what Ms Thornberry suggested.

And these figures only account for the direct effect of cutting corporation tax. That is, they don’t account for the way that different tax rates might affect where companies choose to locate and invest.

For example, companies might choose to move their operations to the UK and pay lower rates, rather than locate elsewhere. They might also comply more readily with tax laws.

There’s no guarantee that either of these things would happen.

But because Labour’s estimates only account for the direct effect they shouldn’t be treated as complete estimates for the overall impact of cutting corporation tax on government finances, or assumed to be the only ones out there.

£60 billion lost tax receipts over the course of this parliament would still create a sizeable hole in the government’s annual income. It’s equivalent an average annual loss of between £12 billion and £13 billion a year, out of an average income of about £800 billion a year over the same time period.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

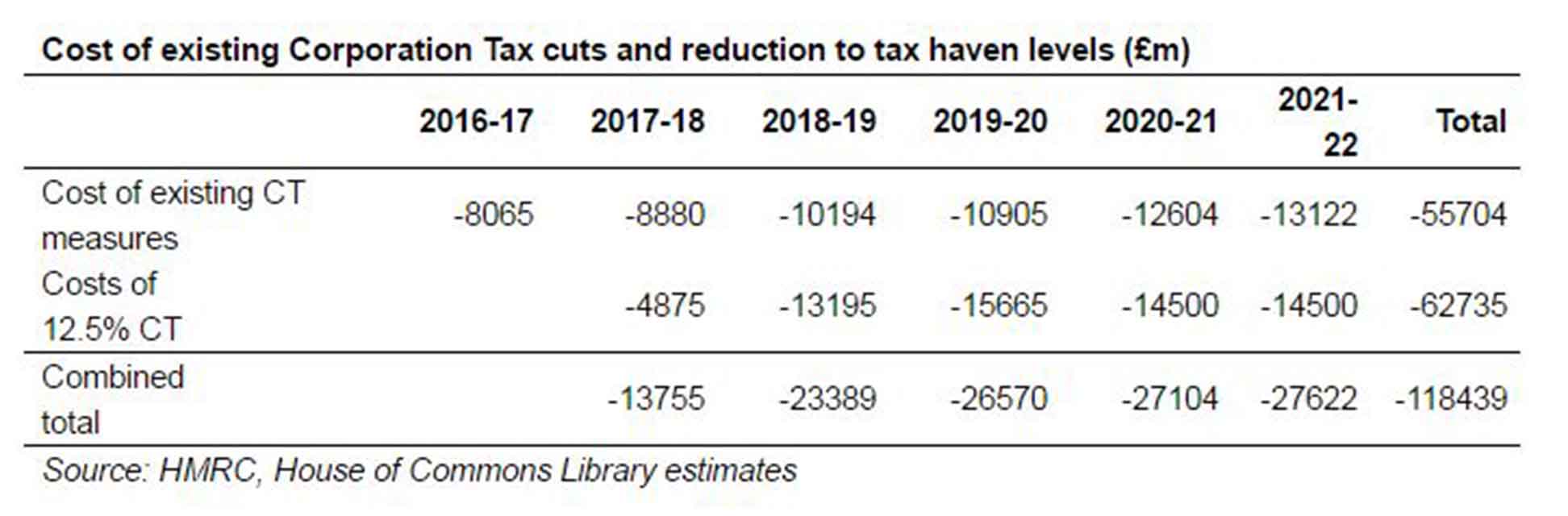

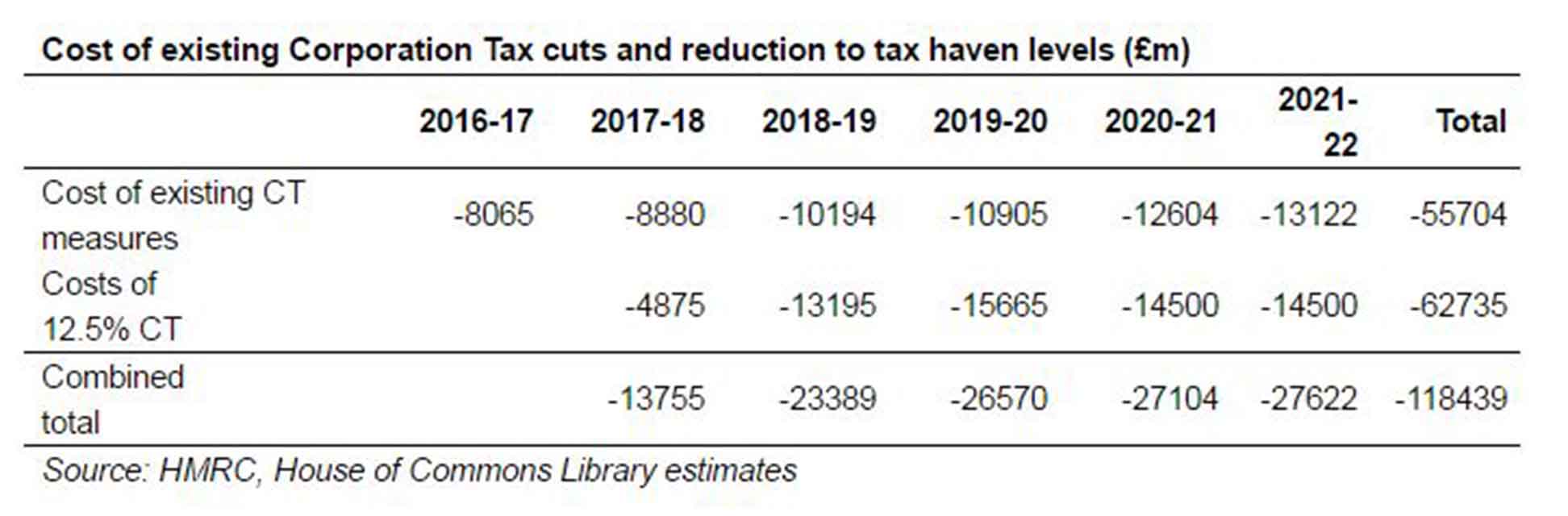

When Jeremy Corbyn made a similar claim in parliament this week, Labour supplied us with this table of estimates:

Labour based its estimates on calculations by HMRC and consultation with the House of Commons Library, a research service for MPs. The figures are estimates for the direct effects of tax cuts and aren’t adjusted for inflation.

Labour based its estimates on calculations by HMRC and consultation with the House of Commons Library, a research service for MPs. The figures are estimates for the direct effects of tax cuts and aren’t adjusted for inflation.

The first line estimates the tax lost each year because of cuts to corporation tax rates since 2010, running up to £56 billion between 2016-17 and 2021-22.

The second line estimates the extra losses that might come from cut corporation tax further and became a ‘tax haven’, as Labour puts it. If we had the same corporation tax rate as Ireland, Labour suggests the government would lose another £63 billion between 2017-18 and 2021-22.

Labour’s press release

A recent Labour press release also quoted these figures incorrectly. It said:

“Estimates from the House of Commons Library suggest that on top of existing corporate giveaways the cost of slashing corporate taxes to match tax havens like Ireland would be a shocking £120bn over the next five years.”

Labour Press, 17 January 2017

That claim doesn’t match the estimates supplied to us by the Labour party.

The table it sent us suggests that the direct costs of cutting corporation tax to match Ireland would be about £63 billion over the next five years, on top of existing ‘corporate giveaways’ worth about £56 billion.

Combined together, these would add up to an accumulated cost of nearly £120 billion, not accounting for the indirect effects of tax cuts.