“Last year the average farm made £2,100 from agriculture and £28,300 from subsidies. The typical cereal farmer actually lost £9,500 by farming cereals.”

The Times, 4 August 2016

The basic point is correct: on average, farmers across the UK make far more money from subsidies than they do from agriculture. Cereal farmers lose money. The exact figures depend on what you class as a ‘subsidy’.

On average, English farms made a £39,000 profit last year from their farming business.

Only £2,100 of this came from agriculture, which is what springs to many people’s mind when they think of farming. If we look at cereal farms alone, they lost £9,500 on agriculture in 2014/15.

On the other hand, the average English farm received £24,900 in subsidies last year. Once you deduct the costs involved in making use of the subsidies, like employing labour and machinery, the benefit is closer to £22,400.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

What do you call a ‘subsidy’?

The figure reached by The Times of £28,300 includes the total profit after costs from the Single Payment Scheme, and the profit after costs from agri-environment payments. These are all monies paid to farmers by the government and the EU.

However, Defra told us that it doesn't class these agri-environment payments as ‘subsidies’ received by farmers. That’s because they are meant to compensate farmers for any income they lose as a result of carrying out work which benefits the environment and isn’t farming, such as planting woodland.

Subsidies relate to money which supports farmers’ income and protects them against things like big changes in market prices.

We have used Defra’s definition of a subsidy in this article, but it doesn’t change the basic story. Whether you just look at subsidies or include all payments, farmers make more money from the EU and the government than they do from agriculture.

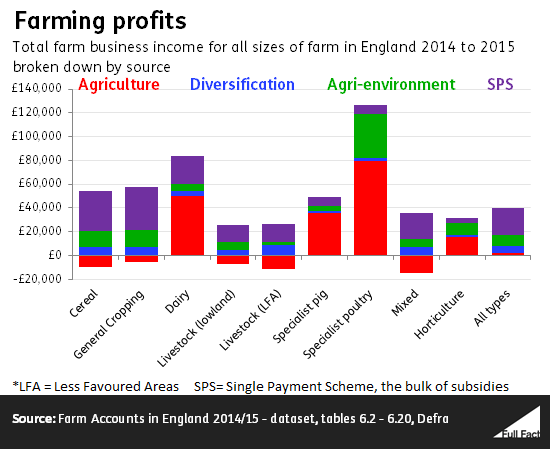

How do farms make their money?

The business income of farms is typically made up of four key areas: agriculture, diversification, agri-environment, and the Single Payment Scheme.

Agriculture covers all costs and money generated through livestock or crops, what we might typically consider the business of farming.

Diversification covers other activities which a farm might do to bring in income, including tourism, rents, or retail ventures.

Agri-environment is mainly schemes which require farmers to manage their land in an environmentally beneficial way. Farmers taking part in these schemes can be compensated by the government for any income they have lost as a result, for example by planting woodland on their land.

The Single Payment is a subsidy provided by the EU and distributed by the government to farmers. It made up most of the subsidy farmers received.

Most types of English farm make more in subsidies than they do in agriculture

The figure changes from year to year and between various sizes of farm. In 2013/14 the average farm’s profit from agriculture was £6,600, which fell to £2,100 the next year. Large farms in 2014/15 made £22,300 from agriculture, whereas small farms lost £6,600.

The amount of profits made from agriculture also varies between different types of farms.

Farms which produce mostly cereal lost £9,500 on their agricultural income because costs for things like machinery and labour outweighed the financial gain from producing the crops and livestock. But, they also received around £37,400 before costs, or £33,900 after costs, in subsidies. So overall, the average cereal farm made about £45,000 in farm business profit in 2014/15.

Poultry farms were much more profitable. Over the same time specialist poultry farms, which have the largest business profit of any of the types listed by Defra, made £126,800 per farm. Well over half of that came from agriculture, £79,300 per farm, and only £8,500 came from subsidies. Once the cost of using these subsidies is taken into account they were worth £8,000.

The amount received in subsidies varies with the size of the farm. All farms receive roughly the same amount per hectare, although the smaller they are the greater a proportion of their profit it makes up.

On average small farm subsidies make up around 78% of the total profit, on medium size farms it’s 61%; and on large farms it’s 46%. Across all farms, subsidies make up around 57% of the total profit on average.

These levels give a general overview for each farm type, but the levels of subsidy and agricultural output will vary from farm to farm depending on their circumstances.

There’s a similar picture in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

There’s a similar picture in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

In Scotland the average farm made £23,000 in business profit during 2014/15. They lost around £21,800 on agriculture, but received around £39,900 in subsidies and other payments.

We should be careful comparing this to the evidence from England, because the Scottish government notes that although the way farming is surveyed in Scotland is largely similar, the types of farm surveyed aren’t all the same. For example Scotland does not include pig and poultry farms in its survey.

In the same year the average farm business profit in Northern Ireland was £24,900. The value of direct payments, agri-environment payments, and other forms of compensation received by farmers came to £25,600.

In Wales the average profit from farm business profit was around £29,400. Of that, £19,600 was made up of subsidies and £2,800 came from agriculture. Before any costs the subsidies were worth £23,300 and the farm made £159,000 overall before costs.

Most of the money for farming subsidies comes from the EU budget

The bulk of subsidies and payments for farmers across Europe comes from the EU’s Common Agricultural Policy.

Until 2015, they were paid to farmers in two main ways.

The first was the Single Payment Scheme, which is based on the amount of eligible land on a farm and how much funding it has historically received. The second way was a number of schemes to improve the environment, quality of life in rural areas and improving the competitiveness of agriculture and forestry.

In the UK most Common Agricultural Policy funding was received through the Single Payment Scheme and environmental improvement schemes.

From 2015 this system of subsidies was changed in line with the reforms to the Common Agricultural Policy.

Because European Union funding is allocated in euros, its exact value to UK farmers varies as the exchange rate changes. In 2014/15 the higher value of the pound against the euro made the value of the Single Payment Scheme less than it has been in previous years.

We have done another briefing on how leaving the EU is likely to impact agriculture in the UK.

There’s a similar picture in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland

There’s a similar picture in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland