Floods, housing and income inequality: factchecking Prime Minister's Questions

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Spending on flood defences

"The investment in flood defences was £1.5 billion in the last Labour government, £1.7 billion in the government I led as a Coalition government and will be over £2 billion in this parliament."—David Cameron

This is almost right in cash terms, although in the current parliament investment spending is set to be about £1.9 billion.

Spending of over £2 billion is expected over the next six years, so including the 2020/21 financial year, which will fall mostly under the next parliament. Five years pass between elections, rather than six.

There's been a rise in this spending even after inflation is considered. But it's a smaller one than that quoted by the Prime Minister.

In 2014/15 prices investment spending was about £1.7 billion during both the Coalition government and the Labour one that preceded it.

This is capital spending—money invested in prevention and protection against flooding and coastal erosion.

It doesn't include day-to-day costs of running the defences, which come under the heading of 'resource' spending in the language of government budgets. Resource spending over the next five years hasn't yet been announced.

So we don't know how total spending will fare over this parliament. Spending was higher in the last parliament than in the one before it, at about £3.3 billion compared to £3.1 billion.

You could argue that looking at spending by parliament isn't the most useful thing to do, as we've written before. That's because the first year of spending during a given parliament will be based in large parts on the previous government's plans.

Home ownership

"Home ownership down to its lowest level in a generation, down every year since he became Prime Minister"—Clive Efford MP

It's correct that home ownership is at its lowest level in a generation, as long as you're happy that a 30-year low can be described as such. The rate of ownership has fallen each year since the mid-2000s.

63% of English households own the home they live in. The last time the proportion was lower than this was in 1984, according to official statistics.

The home ownership rate in England has fallen each year between 2009/10—the year before David Cameron became Prime Minister—and 2013/14. But that was the continuation of a trend that began in the mid-2000s, when the proportion was almost 71%.

We discuss some possible reasons for the decline in home ownership in a previous article.

Solar panels

"What percentage of solar panels have been installed in Britain since this government took office in 2010? … the answer is 98%."—David Cameron

Solar panels were installed at 10,000 sites in May 2010, compared to 816,000 sites in November 2015.

That would mean sites installed by the time the Coalition came into office would make up just over 1% of the current sites, assuming they're still in operation.

The government is currently holding a consultation on plans to reduce some solar power subsidies.

House building

"We built 700,000 houses since this government came to office in 2010"—David Cameron

This is correct. 705,000 homes have been completed nationwide since May 2010, when David Cameron became Prime Minister.

Some will have begun construction while the previous Labour government was in office.

There were close to a million built over the same length of time under Labour immediately before the Coalition took office.

Most of these were built privately or by not-for-profit housing associations, with a handful constructed by local councils. The government said on 4 January that it would "directly commission" companies to build "new affordable homes".

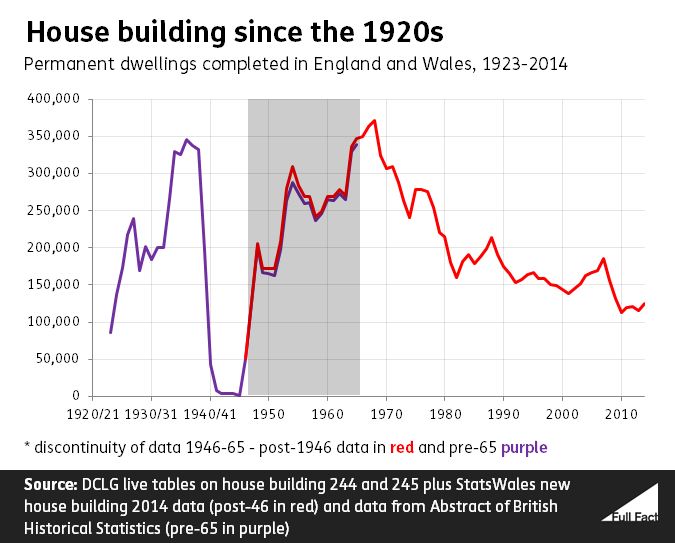

Looked at over the longer term, the number of homes built in England and Wales has been in decline under various governments for decades.

Income inequality

"By last night FTSE 100 chief executives will have been paid more for five days work than the average UK worker will be paid for the whole of 2016"—Debbie Abrahams MP

This claim seems to come from calculations from the High Pay Centre think tank that were widely reported yesterday. They're not perfect, but the general point that chief executives of large companies make a lot more than other workers is correct.

The claim is actually that FTSE 100 chief executives earned more in under two days of work (Monday 4 January and Tuesday 5 January) than the average for the year.

The High Pay Centre analysis compares the average yearly earnings of all full-time workers in the UK with those of FTSE 100 bosses.

The median salary for full-time workers was £27,645 in 2015, according to provisional figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS). The High Pay Centre has compared this to the mean salary for FTSE 100 chief executives in 2014. It makes that number £4,964,000 based on its own analysis of companies' annual reports.

Translating that figure into an hourly rate of £1,260 based on a 12-hour day with not much time off means that it would take a person on that salary less than two working days to earn the same as the median UK employee in a year.

This compares one kind of average (the median) with a different kind of average (the mean), in different years.

On a like-for-like comparison, the pay difference narrows. But whether taking mean or median, the figures suggest that the average FTSE 100 chief executive earned 140-150 times the average worker in 2014.

This is taking the High Pay Centre figures for FTSE 100 pay at face value—it acknowledges that there are other ways of measuring this.

"Since I've become Prime Minister income inequality has actually fallen whereas it went up under Labour"—David Cameron

There's no single definitive measure of income inequality in the UK. There are figures which show a fall on the Prime Minister's watch but these aren't very significant trends.

The ONS describes the recent trend in income inequality as "broadly flat".

One of the most commonly used measures in this area is called the 'Gini coefficient'. This shows the distribution of household incomes across the country from a scale of 0 (total equality) to 100 (total inequality).

So a lower Gini coefficient represents less income inequality.

It's down slightly since 2010 according to both the ONS and the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS). The IFS has warned that recent falls could prove temporary, but this will depend on the policies adopted by the current government.

It says that inequality fell in the years following the recent recession due to the fact that incomes in general fell while the value of certain benefit entitlements increased, which boosted the income of poorer households and left those towards the top with more significant falls.

The trend on this measure under Labour is volatile and can't be summed up by one figure. Inequality did rise in the years up to the recession in 2009 and fell in the following years. Depending on the measure you choose, Labour either left office with a similar or a slightly higher level of inequality on these measures, but these changes are dwarfed by the large rises in inequality in the 1980s.

All these figures use a common but not comprehensive indicator of inequality. For instance, just looking at the incomes of the top 1% compared to everyone else, inequality has been rising almost consistently since the 1980s, with a dip after the recent recession as discussed above.