“Don’t be fooled by the Tories’ “pay rise” for public sector workers. Because of inflation it actually amounts to a pay cut.”

Labour party, 24 July 2018.

The government’s recently announced pay rises for public sector workers are either above or ever so slightly below inflation. These cover one million of the 5.4 million public sector workers. Other public sector workers have been offered other pay deals previously.

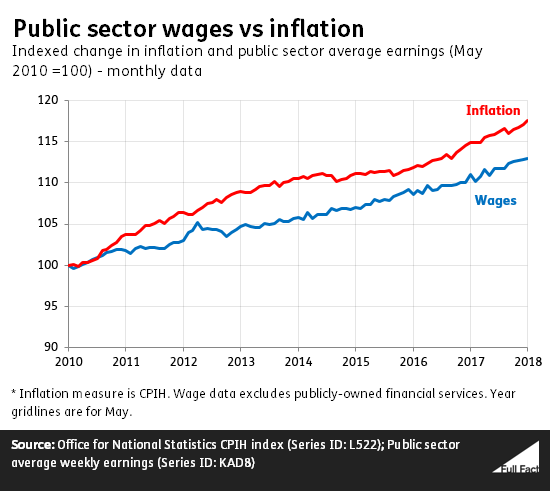

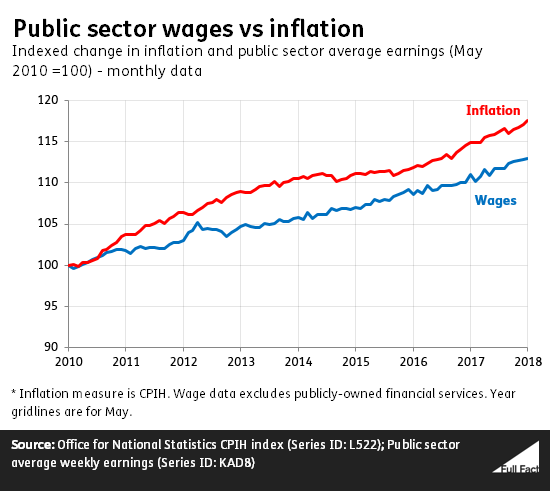

Pay rises above inflation are called “real terms” pay rises, because yearly wages increase more than inflation (a measure of the change in the cost of living). When pay rises are below the level of inflation, they can be considered real terms cuts as prices are rising quicker than yearly wages.

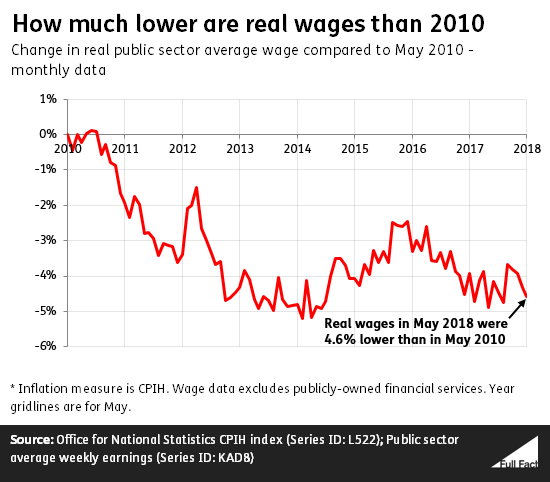

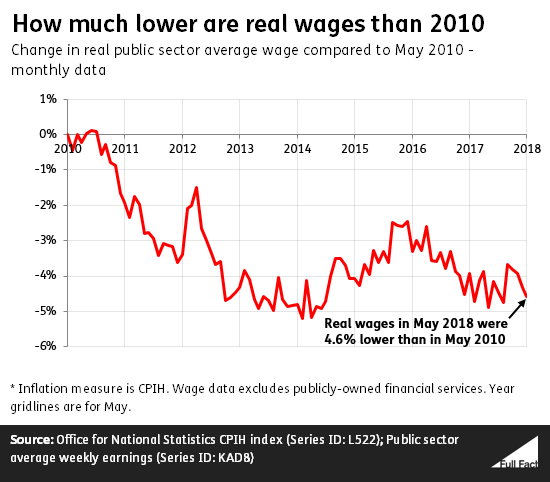

Since May 2010, public sector pay in real terms has fallen by 5%.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

What was the recent announcement?

The government announced a range of consolidated and non-consolidated pay rises for public sector workers. Consolidated pay rises are permanent salary increases. Non-consolidated pay rises are one-off bonuses.

The armed forces will receive a pay increase of 2.9%, teachers on the main pay range will receive 3.5% and prison officers will receive pay rises of 2.75%. After inflation (projected by The Office for Budget Responsibility to be an average of 2.1% over the next 12 months) these all amount to real terms pay rises.

Of all these groups, only teachers on the main pay range will get a permanent real terms increase. For prison officers and the armed forces, 0.75% and 0.9% of their pay rises will be a one-off non-consolidated payment. After that one-off increase, their remaining base salary will be 2% higher than before, which is below projected inflation and so amounts to a real-terms cut.

Doctors and dentists will receive pay rises at different levels, some (for example specialty doctors) will receive real terms increases and some (like consultants) will receive real terms cuts.

The police will receive a 2% pay rise, just shy of inflation, and thus amounting to a real terms cut.

Teachers on the upper pay range and in leadership positions will receive rises of 2% and 1.5% respectively—a real-terms cut.

We don’t know when the pay rises will come into effect. The longer they take to come into effect, the longer these public sector workers will be effectively experiencing real-terms pay cuts (as their wages will be stable while the cost of living increases because of inflation).

Our calculations assume the pay rises come in as soon as possible, and compare projected earnings in real terms over the next 12 months, with earnings over the previous 12 months.

Depending on how you look at it, pay rises below the yearly level of inflation could still be considered real-terms pay rises, but for less than a year. For example teachers in leadership positions stand to get a pay rise of 1.5%. That would increase their income in real-terms for around nine months, at which point their pay in real terms would be the same as it started, and then start to fall.

What has happened prior to the announcement?

From 2011 until this year, the government limited the pay increases public sector workers earning over £21,000 could receive.

In 2011 and 2012 pay was frozen, so there was no increase. From 2013, pay was capped at an average rise of no more than 1%.

Last year the Government ended the cap and since then different groups of public sector workers have been offered different pay deals, in addition to those whose pay deals were announced last month.

In March NHS staff (not including doctors, dentists or senior managers) were offered a rise amounting to between 4.5% and 29% over the next three years—for some, a real terms increase. You can read more about the NHS pay deal here.

Meanwhile pay guidance issued by the Treasury and Cabinet Office in June limited government departments to raising average civil servant pay between 1% and 1.5%—a real-terms cut.

Public sector pay is 5% lower in real terms than in May 2010

Since the Coalition government took office in 2010, public sector wage growth has largely been lower than the rate of inflation—a real terms cut.

Cumulatively, that means that public sector wages are now around 5% lower in real terms than they were in May 2010.

Cumulatively, that means that public sector wages are now around 5% lower in real terms than they were in May 2010.

Analysis from the Office for National Statistics shows that since 2011 public sector pay grew slower than private sector pay for most of that period.

Cumulatively, that means that public sector wages are now around 5% lower in real terms than they were in May 2010.

Cumulatively, that means that public sector wages are now around 5% lower in real terms than they were in May 2010.