Economy introductions: the idea behind interest rate changes

By changing short-term interest rates, the Bank of England can alter the cost of borrowing money in the rest of the economy. Its aim is to “influence the overall level of activity in the economy”, and ultimately inflation.

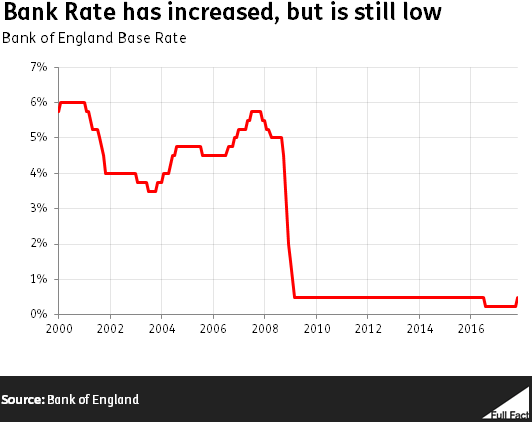

In November 2017, the Bank of England set the official Bank Rate at 0.5% annually—the first increase since July 2007.

Even though Bank Rate has increased, it remains at a low level compared to the past.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Higher interest rates should mean slower growth

When the Bank of England’s interest rate increases, it’s more expensive for banks to fund themselves.

In theory, this means they’ll lend to businesses and households at higher rates too, so a Bank Rate increase should mean higher interest rates for everyone else. Interest rates on new loans tend to rise ahead of a Bank Rate increase, when the market anticipates the increase.

The Bank Rate change won’t affect all borrowers. Less than half – 40% - of existing mortgages are on a floating, or variable rate deal, according to Bank of England data. These are likely to change soon after a Bank Rate change. Nearly all existing loans to businesses are on a floating rate.

This gives businesses and households less incentive to borrow and more incentive to save.

Higher interest rates in the UK might give some investors an incentive to save money here, rather than in countries that have lower interest rates. This puts upward pressure on the value of the pound soon after the increase is announced, although the precise long-term effect is uncertain.

Other investors switch from holding on to government bonds or shares in companies, reducing their price.

Higher interest rates should mean slower price rises

According to the theory, when interest rates are higher less money will be spent. When less money is being spent, prices for consumer goods rise more slowly.

If prices rise too slowly then inflation will fall below the Bank of England’s inflation target, set by the Treasury. The current target is for prices to rise by 2% per year.

Usually at that point, the Bank of England would cut interest rates again, making it less expensive for other banks to borrow and lend money and, as a consequence, pushing down interest rates for businesses and households.

Saving would become less attractive because interest rates on savings accounts would fall, while borrowing and spending would become easier—so the economy would start growing more quickly.

Sometimes the Bank prioritises keeping a suitable level of employment and economic output over hitting its inflation target exactly, as it did in August 2016.

Interest rate changes take time to affect the economy

Changes in this interest rate should, in theory, influence other interest rates, the growth rate of the economy, and the rate of price inflation. But monetary policy takes time. Although some of its effects take hold very quickly—like the effect on people’s expectations—the full effect on inflation takes up to two years to work through.

Interest rates have been low since 2009

The Bank of England hasn’t raised its official rate since July 2007, when the rate went to 5.75%. By March 2009 the bank rate had been cut to 0.5%, and it stayed that way until August 2016, when it was cut to 0.25%, a historic low.

The Bank has also used new ‘unconventional monetary policies’ like quantitative easing to try and encourage economic growth and push inflation towards its target level.