Miliband, Marr and housing

Labour have promised to give those who rent their home a "better and more secure future" through new regulations.

From reading some of the accompanying headlines, you might be forgiven for thinking that Labour are proposing to cap rents. But that's not the case: the proposal involves to limiting the increase in rent during a tenancy, not the initial level of rent. These interventions are known as rent controls and rent stabilisation, respectively.

Rent controls were introduced in the UK during World War One and similar systems exist today, for example in the Netherlands. In contrast, rent stabilisation is more common in other European countries. The system that Labour are proposing would mean that after the start of a tenancy, rent on that tenancy can rise by no more than inflation, as measured by the Consumer Prices Index of inflation.

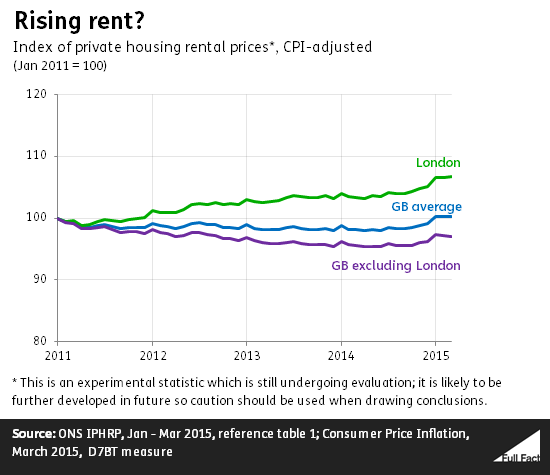

It seems that, overall, rent has been rising roughly in line with inflation over the last four years, according to experimental figures from the ONS.

London saw rent rising faster than inflation, while the rest of Great Britain saw average rents rising slightly behind inflation.

Wages have not been rising in line with inflation though, so even though rents have increased broadly in line with inflation, this doesn't mean that they have remained as affordable as in 2011.

The Labour leader, Ed Miliband, was questioned by Andrew Marr on his party's housing policy. We've checked some of the key claims from the discussion.

"There are 11 million people in generation rent"—Miliband

There are 4.4 million privately rented households in England, containing about 11 million people. That includes families as well as single people; not all of them expect to buy a house. But the term 'generation rent' doesn't usually apply to this whole group.

'Generation rent' has been defined by the social research agency NatCen as "a generation with no realistic prospect of owning their own home in the next five years". NatCen estimated that just over a third of 20-45 year olds are in 'generation rent'.

Under this definition, the term includes people who want to buy for the first time but are prevented; it also includes people who don't want to own a house.

Miliband doesn't seem to be using the term in its technical sense here. He's not alone, the term is widely and differently used in the media; it also refers to various campaigning organisations, Because of this, it's difficult to put an exact figure on the number in 'generation rent'.

When asked whether his proposals would work, Miliband had this to say:

"Look what happened in Ireland. In 2004 they introduced this system, and it has worked ... There are more people renting in the private sector in Ireland than there were eleven years ago"

Miliband is right: the number of private renters in Ireland has risen. Between 2006 and 2011, the number of Irish households which were rented either from a private landlord or a voluntary body rose from 200,000 to 320,000. In 2011, this group made up 19% of all private households, an increase from 13% in 2006.

But the system in Ireland is quite different from the one Miliband is proposing: rent rises aren't linked to inflation. In fact, in 2014, rents in the private rented sector in Ireland rose by 5.8% but CPI fell by 0.3% in the year to December 2014. Instead, the rent is limited to the amount "which a willing tenant not already in occupation would give and a willing landlord would take for the dwelling". One commentator regards the current system for private rental in Ireland as "largely unregulated", so it's not really comparable to Labour's proposals.

"Britain is almost unique in the world having these insecure one-year tenancies"—Miliband

Compared to some other countries in Western Europe, UK tenancy agreements seem quite insecure. "Most countries have stronger regulations about rent rises within tenancies than the UK", according to a study of European countries. In the UK, rental contracts are typically 6 months long, with no reason needed to evict tenants. This is shorter and less secure for tenants than typical contracts in Germany, France, Spain Italy and Ireland, though different countries have varying attitudes (£) to renting.

Britain's rental rules are insecure compared to other European countries. But to imply that Britain's tenancies are amongst the most insecure in the world is too simplistic. According to the UN Special Rapporteur on adequate housing, "tenure insecurity is a global phenomenon", and not just confined to the UK.

"We had rent controls in the 1970s and they went because they weren't working"—Marr

Marr is right that the UK had rent controls in the 70s, and he's right that they were abandoned. As to whether those controls were working or not, that's up for debate.

Rent controls were first introduced in Britain in 1915, to address profiteering by some landlords during housing shortages in World War One. These measures were originally intended to be temporary, but continued to apply to some rental agreements until deregulation under the 1988 Housing Act.

Technically there are still a small number of tenants whose rent is regulated and who are entitled to have a 'fair rent' set on their property by a rent officer. These regulated tenancies are increasingly rare, as they typically require the tenancy to have begun before January 1989.