Tax dodging: how big is the problem?

“Estimating the tax gap is not an exact science”.

The “tax gap” is the difference between the amount of tax HM Revenue and Customs (HMRC) thinks it’s owed in theory, and what it actually ends up collecting.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

HMRC’s estimates

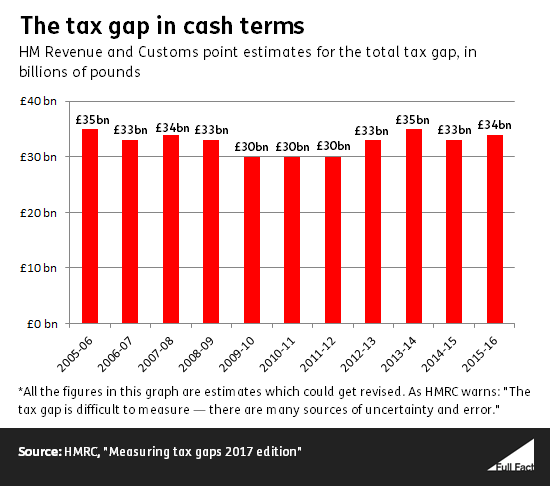

HMRC estimates that £34 billion of tax was never collected in 2015/16, compared to £33 billion for the year before.

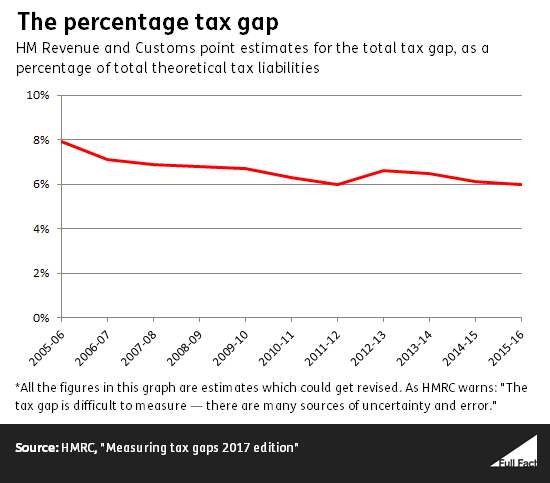

Uncollected taxes can also be measured as a percentage of all taxes owed to HMRC. In 2015/16, this measure stood at 6%, compared to 6.1% in 2014/15. 6% is the lowest percentage since 2011/12, and lower than almost 8% back in 2005/06.

HMRC summarises this as “an overall downward trend over the past decade, with some year-on-year variations.”

HMRC says the percentage figure gives a better idea of tax compliance over time, “because it takes account of some of the effects of inflation, economic growth and changes to tax rates, where the cash figure does not.”

But there’s a lot of uncertainty to these figures, which tend to be revised from year to year. That means none of HMRC’s figures should be treated as exact, and it would be risky to read too much into the trends.

For instance, the government last year estimated the tax gap in 2014/15 to be £36 billion, or 6.5%. It has now revised that estimate to £33 billion, or 6.1%. A big factor this year has been a revision in estimated size of the tax gap in the “hidden economy”, reducing it by between £2.5 and £2.7 billion a year.

What causes the tax gap?

There are lots of reasons for the tax gap.

The biggest cause, according to HMRC, is people failing to “take reasonable care” in recording transactions and preparing tax returns (costing an estimated £6.1 billion in 2015/16).

Just below this is “legal interpretation” (costing an estimated £6 billion). This is where there is a difference in how a taxpayer and HMRC say they understand the tax law on a specific case.

Tax evasion means illegally hiding activities from HMRC to avoid tax. This cost an estimated £5.2 billion.

Tax avoidance is the exploitation of legal loopholes to avoid tax. It cost an estimated £1.7 billion.

Not everyone agrees with HMRC’s estimate of the tax gap

Richard Murphy, who runs the website Tax Research UK, estimated that the tax gap would be £122 billion in in 2014/15. HMRC currently estimates that the tax gap in that year was £33 billion.

There are numerous areas in which Mr Murphy calculated the tax gap differently to HMRC.

The single biggest factor, Mr Murphy argues, is that the “shadow economy” is far bigger than HMRC estimates. This is “economic activities that are not recorded or declared to avoid government regulation or taxation”. He predicted this would lead to a tax gap of £48 billion in 2014/15. HMRC estimated that the “hidden economy” had a tax gap of £6.2 billion in 2014/15.

Mr Murphy also argues that HMRC underestimates tax avoidance, because it does not include the use of tax havens, as well as sums evaded by companies like Google and Amazon. He estimated the tax avoidance tax gap would be £19 billion a year in 2014/15, including disputes over legal interpretation. HMRC’s figure for 2014/15 was £7 billion.

That complaint is echoed by recent work by economist Gabriel Zucman, fuelled by the findings of the “Paradise Papers” investigation into offshore tax havens. Zucman estimates that €12.7 billion (£11.3 billion at today’s exchange rate) of tax is avoided by multinational corporations in the UK each year through the use of such havens.

Drawing on this, Mr Murphy recently produced a new estimate that tax evasion gap (not including legal interpretation disputes) was 8.4 billion in 2015/16. HMRC says it was £1.4 billion.

So whose estimate is better?

It is hard to say, and no one can talk about a “true” figure with great confidence.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) reviewed HMRC’s tax gap estimates in 2013.

According to the National Audit Office (NAO), the IMF’s review “concluded that HMRC produced one of the most comprehensive studies of the tax gap available internationally. It concluded that in general the methodologies HMRC used to estimate the tax gap were sound”.

However, the IMF “also recommended that HMRC improve its estimates of undetected non-compliance”, according to the NAO.

Ultimately, the NAO notes that “The tax gap is inherently difficult to estimate and HMRC acknowledges that no estimate of the tax gap can be definitive and that its estimates carry a degree of uncertainty”.

“Around two-thirds of the tax gap is estimated using established methodologies, with the remainder estimated using developing and experimental methodologies.”

HMRC does not know the level of uncertainty in 60% of its calculations, the NAO says.

HMRC’s methodologies are varied and change year-on-year, and differ from those of others like Mr Murphy. This is a big reason why we get such fluctuating estimates.