What was claimed

Water bills are up 40% since privatisation.

Our verdict

Correct in real terms in England and Wales between 1989 and 2014/15. Most of that rise happened between 1989 and 1995. Bills have fallen slightly in real terms since 2009/10.

Water bills are up 40% since privatisation.

Correct in real terms in England and Wales between 1989 and 2014/15. Most of that rise happened between 1989 and 1995. Bills have fallen slightly in real terms since 2009/10.

“New reports have revealed the staggering public cost of privatised water – water bills are up 40% since privatisation.”

The Labour Party, 12 October 2018

It’s correct that between 1989, when water services were privatised in England and Wales, and 2014/15, average household water bills rose by 40% above inflation.

But the 40% rise alone doesn’t quite tell the whole story. Most of that increase was in the early years after privatisation, and more recently bills have been falling slightly in real terms. They are expected to continue doing so.

A reason for this recent fall is that water services are, to an extent, publicly regulated. Although water services are run by private companies, there is a national regulator of the regional water companies in England and Wales (called Ofwat), which can set price caps on what water companies can charge customers.

Ofwat argues that privatisation has allowed significant, and more efficient investment in improving services. It recognises that services have broadly increased in quality since privatisation, but other research suggests that water companies could do more to deliver value for customers, and have prioritised increased dividends for shareholders over providing better value.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Since water and sewerage services were privatised in England and Wales in 1989, the average annual household water bill in England and Wales rose by 40% above inflation up to 2014/15, according to the public spending watchdog the National Audit Office (NAO). That means the average bill in 2014/15 (£396) was 40% higher than the average bill in 1989, once you convert the 1989 bill into 2014/15 prices. The average bill today is £405.

Most of that rise happened in the early years of privatisation. From 1995 to 2014/15 the increase was smaller—9% in real terms. More recently, average bills have started to fall (although they are still higher in real terms than they were before privatisation). They fell by 2.6% in real terms between 2009/10 and 2014/15, and Ofwat (the regulator of the water industry in England and Wales) ruled that average bills should fall by 5% in real terms between 2014/15 and 2019/20.

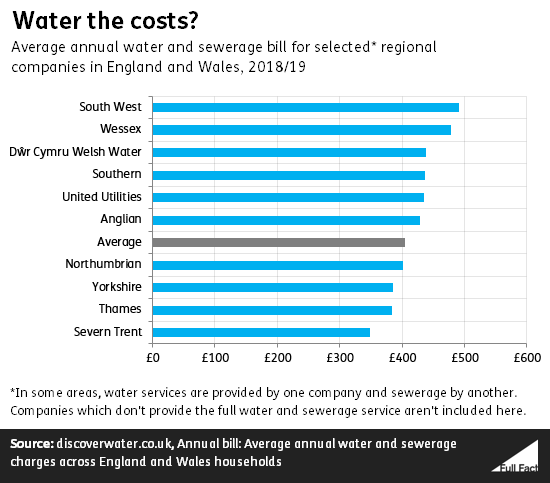

Bills can also vary a quite a bit depending on where you live.

It helps to understand how the water system is currently regulated.

Unlike something like energy (where you can switch between service providers) there is not a competitive market for water services at the household level. Most water and sewerage services are “regional monopolies”: most consumers don’t have a choice of water provider, rather they get the services of whichever private company covers their area.

And these regional monopolies are subject to a relative degree of public oversight. Ofwat has a number of legal duties it has to perform, including to protect the interests of consumers, and to ensure that water companies are financed to carry out their functions properly.

One of the main ways it carries out these duties is by setting price controls covering five-year periods. These set limits on how much water companies can charge customers, whilst also setting targets for what services they must deliver (such as improvement works). The controls are set against considerations of both what is needed to properly fund improvements, and how much customers will be charged. .

By accepting Ofwat’s price controls (they are sometimes subject to negotiation), the water companies agree to what they have to deliver over the next five years, and the budget that they have for doing this. If they can do this for cheaper than the price set by Ofwat, then they get to keep the profits. They also accept the risk that, if they deliver it for more than the price cap, they will suffer losses.

According to the House of Commons Library, the main aim of privatisation was to raise “revenues and to rely on the capital market” to fund the major requirements of the industry in future. Ofwat says that it has overseen £108 billion of investment by water companies since privatisation. The NAO also says that most of the measures Ofwat uses to monitor performance have improved over time, although the assessments only go up to 2009/10.

In 2015 it noted: “The proportion of properties at risk of low pressure fell from 1.33% between 1990 and 1995, to 0.01% in 2009-10. Unplanned supply interruptions of 12 hours or more fell from 0.33% of properties to 0.06% of properties. The only measure that has not improved is the percentage of properties experiencing sewer flooding.”

But the NAO also suggests that Ofwat could do more to control prices, saying in 2015 that the current price cap regime “does not yet achieve the value for money that it should” as it doesn’t “balance risks appropriately between companies and consumers”. The government has also criticised the “excessive profits” and use of “opaque financial structures based in tax havens” by some water companies.

Academics from the University of Greenwich argue that the current regulation is too generous to the water companies “On average, over the past ten years, water and sewerage companies have paid over £1.8bn per year in dividends [to shareholders], which equates to about £75 per household per year. This is an expensive way to finance infrastructure.”

The government strongly rejects the idea of re-nationalisation that has been proposed by Labour , but has welcomed Ofwat’s plans to reform water companies’ licences to better reflect the interests of customers, with the government stating that it is willing to give Ofwat strong powers to do this if necessary.

Full Fact fights for good, reliable information in the media, online, and in politics.

Bad information ruins lives. It promotes hate, damages people’s health, and hurts democracy. You deserve better.