A-Level results: beware of the headlines

A-Level results day tends to bring a lot of dramatic headlines. Depending on who you listen to, the same set of results could signal record-breaking high achievement, or a sudden drop in performance.

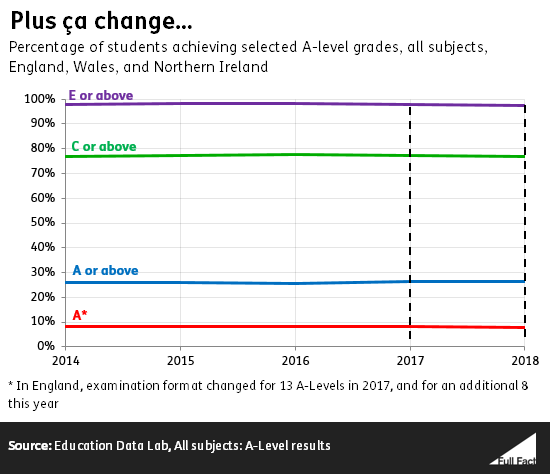

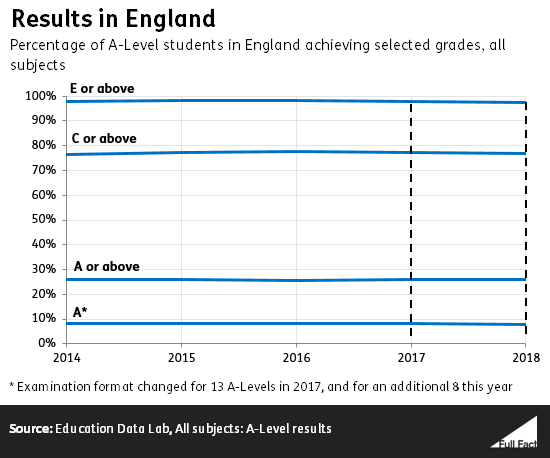

But ultimately, the bottom line this year is: the results don’t show big changes. Most year-on-year variation in A-Level performance is very marginal across England, Wales and Northern Ireland (most students in Scotland don’t sit A-levels). The level of students, or selected subgroup, achieving a particular grade tends to go up or down by a few tenths of a percentage point on the year before.

The drop of 0.4% in the number of students achieving a C or above this year is equivalent to just over 3,000 students (we can’t give an exact number as pupil numbers fluctuate each year).

And neither does comparing results with the year before tell us very much. Some year-on-year variation in performance is pretty much inevitable. To get a sense of, say, whether fewer students are getting the top grades, or whether boys are increasingly outperforming girls, you need to look at the data in a longer context.

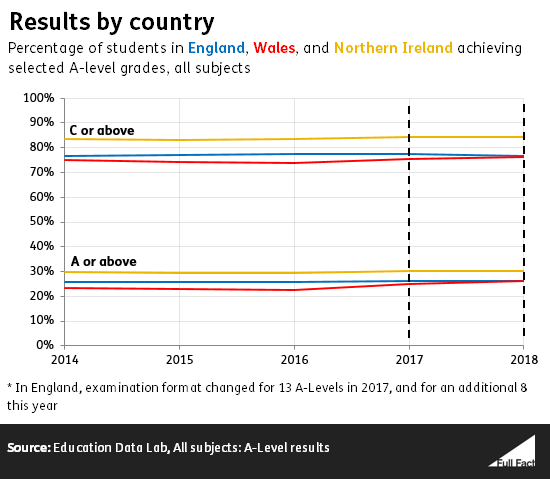

And when you do this, general performance levels appear fairly stable. Where changes can be observed this year, for instance boys getting more top grade than girls, these tend to fit in with longer term trends. Wales has also shown a significant improvement in recent years.

So while the number of students taking A-level French continues to plummet, it’s at least worth keeping the following phrase in mind when thinking about A-level results: plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

The data analysed in this article all comes from the FFT Education Datalab.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Overall performance is stable

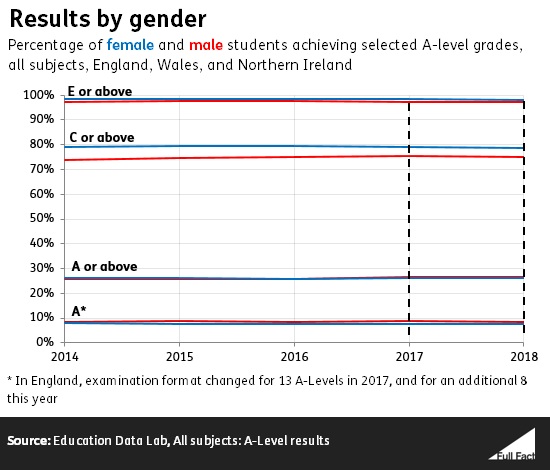

8% of students achieved the top A* grade this year, down 0.3 percentage points on the year before. The number achieving a C or above is also down 0.4 percentage points, to 77%. But in the longer context, these levels look pretty stable, and are very similar to performance four years ago. More boys achieved the top A* grade (8.5%) than girls (7.6%) this year. This is in line with recent trends, where the level of A*s achieved is typically 0.5-1 percentage point higher among boys than girls.

More boys achieved the top A* grade (8.5%) than girls (7.6%) this year. This is in line with recent trends, where the level of A*s achieved is typically 0.5-1 percentage point higher among boys than girls.

In the last two years, boys have achieved fractionally more As than girls, whereas girls were fractionally higher in the three years before then. A significantly higher level of girls achieve a C or above, although the percentage of boys achieving that grade has been rising in recent years, contributing to a slight closing of the gap in performance.

Performance by country: Wales on the rise

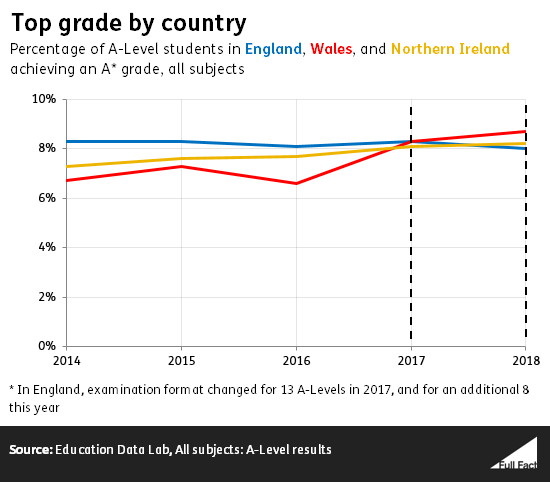

As has been the case in the past few years, students in Northern Ireland performed better than those in England and Wales in terms of achieving either an A or above, or a C or above. The gap in performance between Wales and England has been closing in recent years, and is virtually zero this year. Wales has also shown a notable increase in the level of students achieving A*s in recent years. Whereas it had been lagging behind England and Northern Ireland in past years, it has caught up and overtaken them in the past two years with a significant rise in performance.

Wales has also shown a notable increase in the level of students achieving A*s in recent years. Whereas it had been lagging behind England and Northern Ireland in past years, it has caught up and overtaken them in the past two years with a significant rise in performance.

Northern Ireland is also showing an upward trend, while A* achievement in England remains relatively stable. The fact that the examination format has changed for many A-Levels in England in last two years means the data for England may not be perfectly comparable.

Has the new A-Level format affected results?

Beginning last year in England, students in some subjects took a new format of A-Level exam for the first time. More subjects moved over to the new format this year. Under the new A-Levels, performance in AS levels (taken the year before) no longer counts towards final grades. They also typically see more of the assessment done by exam, with other types like coursework only used where it seen as necessary to test “essential skills”.

Last year, the Office of Qualifications and Examinations Regulation (Ofqual)—which regulates exams in England—noted that students tend to perform less well in the first year of a new style of exam, as teachers are less familiar with teaching them. Ofqual says it has measures in place to make sure grades are comparable with prior attainment of students, accounting for the expected dip in performance.

Overall performance in England does not seem to be dramatically affected. The level of As or above, and A*s, rose slightly in 2017, but this year A*s dropped slightly, whilst the level of As or above stayed the same. The most notable variation comes in the C or above performance: it rose by 0.7% in 2015, and 0.3% in 2016, before falling by 0.2% last year and 0.5% this year. There were also some suggestions that the new exam format would favour boys over girls, due to the increased amount of exam-based assessment. This generated some headlines as boys overtook girls in achieving an A or above for the first time in the UK.

There were also some suggestions that the new exam format would favour boys over girls, due to the increased amount of exam-based assessment. This generated some headlines as boys overtook girls in achieving an A or above for the first time in the UK.

But as the FFT Education Datalab points out, this is the continuation of a long-running trend where the gap between boys and girls had been closing, and boys had actually overtaken girls in achieving an A* or A in England back in 2014. What’s more, performance among boys and girls in the “reformed” subjects with new-style exams was virtually identical in England.

This analysis from 2017 by Ofqual does, however, suggest that performance was lower overall in “reformed” subjects. While overall achievement of A* and A/A* went up in England, the level fell in 10 out of 13 “reformed” subjects, and on average among these subjects overall.

So some early trends have been observed, but it’s probably too early to make any dramatic conclusions about the impact of the new exams yet.