Apprenticeships: a qualified success

- Apprenticeships have changed a great deal since the 1950s, from being three years long and mainly for young people to being shorter and for all ages

- The number of apprenticeship starts each year has been substantially higher under the Coalition than under the last Labour government, but mainly for the over 24s

- There are disagreements over the future of overall funding and whether or not reforms to raise the standards of apprenticeships go far enough

The government committed to deliver two million apprenticeships by the time of the 2015 general election. The target has been hit, but questions have been raised as to how much it should be heralded as a success story.

Apprenticeships are paid jobs that incorporate on- and off-the-job training and are open to everyone over the age of 16 in England and not in full-time education. Apprentices are awarded a nationally-recognised qualification when they complete their contracts.

Apprenticeships haven't always been this way - in the 1950s apprentices used to be mostly teenagers - and there have been multiple transformations of what's considered to be an apprenticeship since then. While the number of apprenticeships is up, some experts like the Sutton Trust have argued they're of poor quality and that the benefits haven't always been felt by the younger age groups.

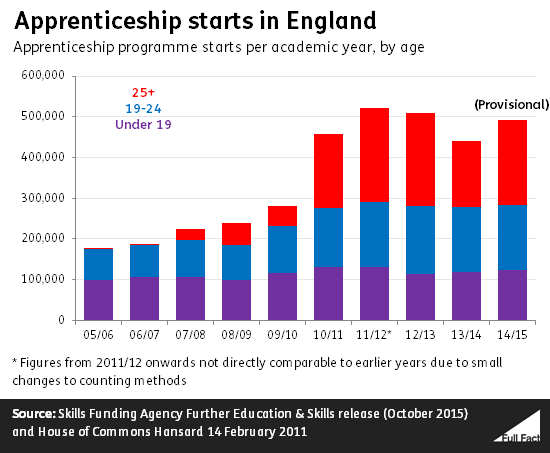

The number of people starting apprenticeships has been rising over the longer term

2.38 million apprenticeships were started between the summer of 2010 and spring 2015.

This incorporates a small fall in the number from 2011/12 to 2012/13. That fall appears to have continued more substantially in 2013/14 but seems to have now recovered based on the provisional figures.

This fall was largely down to a decline in starts among the over 24s. From August 2013 people aged 24 and above considering doing higher or advanced level apprenticeships were no longer eligible for a government grant but had to take on a means-tested loan instead. The loans were withdrawn the following March because of poor take up.

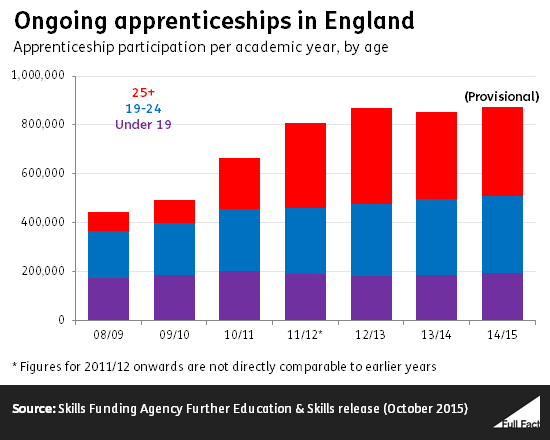

The fall is less significant if you count those already in apprenticeships at any one time rather than just the new starts.

Over 24s saw the biggest increase

Back in the 1950s apprenticeships were largely for teenagers as a route into a new job, learning their trade for about three years with the goal of being taken on full-time. But once they were opened up to the over 24s by the Labour Government in 2008, many jumped at the opportunity.

But some companies are now shifting their employees onto apprenticeships in order to certify training for their existing staff, according to a recent report by Ofsted. The Institute for Public Policy Research made the same point in a 2011 report. In that year 70% of apprentices worked for their employer before starting their apprenticeship, compared to about 50% in 2007.

In 2011, some of the money that had been spent on the abolished Train to Gain scheme (providing vocational training to adult employees) was transferred to fund adult apprenticeships instead. Critics suggested that adults gaining skills under that training scheme were simply being "classified as new apprenticeships" as a result. So the increase in apprenticeships among the over-24s isn't necessarily an increase in training that wouldn't have happened otherwise.

Questions over the quality of apprenticeships prompted the government's Richard Review in 2012 which concluded that apprenticeships "should be targeted only at those who are new to a job or role that requires sustained and substantial training."

A balance between quality and quantity

In 2012, the government set a minimum duration of a year for apprenticeships in order to "drive up quality".

But the National Audit Office (NAO) has said it's too early to tell if this has had any effect on quality. It also raised concerns about the impact of this reform on take up of apprenticeships by 16 to 18 year olds:

"Longer apprenticeships, in the context of reduced funding [for 16-18 year old provision], might lead to fewer apprenticeships in total, which, in turn, could reduce overall participation."

It also warned that:

"employers do not have to have apprentices and there is a risk that fewer may do so if they have to meet the training costs themselves or perceive the process to be a burden".

Ofsted has more recently commented that "in recent years, inspectors have seen too much weak provision that undermines the value of apprenticeships, especially in the service sectors and for learners aged 25 and over". It said there were "still far too few 16 to 18 year olds starting an apprenticeship" and that schools weren't doing enough to promote them.

The government has also sought to increase the number of higher level apprentices. In 2011 it introduced a £25 million fund for advanced and higher apprenticeships—the equivalent of 2 A level passes and a foundation degree respectively.

This seems to be working, apart from the decline in 2013/14 for the over 24s affected by the new loans. In the 2012/13 academic year, 9,800 people started higher apprenticeships—up from 3,700 in the previous year but higher than the 9,200 in 2013/14. Since then, the government announced a further £40 million to deliver an additional 20,000 higher apprenticeship starts in the 2013/14 and 2014/15 academic years, and about 19,000 people were thought to have started higher apprenticeships in 2014/15.

Still, experts are divided on whether the reforms go too far or not far enough. A Sutton Trust report in 2013 argued that a year long apprenticeship isn't enough. It said the majority of apprenticeships have been "below the level 3 standard required for most technician or paraprofessional jobs", arguing that instead "three year, high standard apprenticeships must become the norm".

Ofsted also commented that there are "still not enough apprenticeships providing the advanced and associated professional-level skills needed in the sectors with shortages".