Grammar schools and social mobility: what's the evidence?

Grammar schools are “horror movie monsters” to their detractors and “beacons of excellence” to their defenders.

From either perspective, the main issue is the role these schools play in ‘social mobility’. The concept has many definitions, but is generally about how easy it is for people from poor backgrounds to make the most of their abilities, especially when it comes to educational attainment.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Poorer children are less likely to go to grammar schools

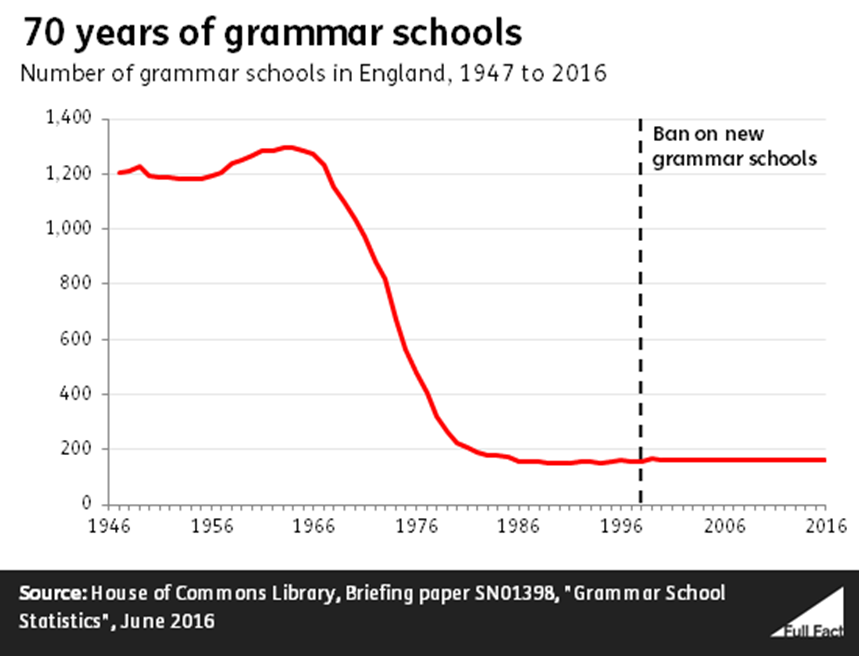

The number of grammar schools in England and Wales peaked in 1964, at almost 1,300, educating almost a quarter of the total student population.

From 1965 onwards there was a decline in the number of grammar schools, as local authorities moved to comprehensive education under pressure from parents and the then Department of Education. The few grammar schools that remain are scattered across England, with concentrations in ‘selective’ counties such as Kent, Lincolnshire and Buckinghamshire.

Now only a small number of pupils in England attend grammar schools—167,000 in 2016, out of around 3.2 million pupils in all state-funded secondary schools.

However, in some local authority areas grammar schools can cater for up to 25% of pupils.

Grammar schools are still an important part of the education system in Northern Ireland, where they account for around one third of secondary schools.

What hasn’t changed is that few children from disadvantaged backgrounds attend grammar schools. Studies of the post-war grammar schools system found children from lower socio-economic backgrounds were less likely to go to grammar schools.

And that’s still the case now.

At the start of 2016 fewer than 3% of students in grammar schools were eligible for free school meals, compared to 14% for all school types (and 17% in grammar school areas).

Eligibility for free school meals is a common (though imperfect) measure for children from low-income families. Eligibility for the meals is based on household income and receipt of certain benefits.

Grammar schools have also been criticised for taking too many private school pupils. About 12% of year 7 pupils in grammar schools didn’t go to a state-funded school in year 6—most of which are thought to have been in private primary schools. This figure can rise to about 20% in some selective areas. Only 2% of year 7 pupils in all state schools in England were outside the state school system in year 6.

Why do so few disadvantaged children attend grammar schools in England?

These low numbers are partly explained by the fact that children on free school meals generally do not do as well academically as other students. In 2016 35% of pupils eligible for free school meals achieved the expected national standard in reading, writing and mathematics, compared with 57% of all other pupils.

But this isn’t just about differences in ability. “Amongst high achievers, those who are eligible for free school meals or who live in poorer neighbourhoods are significantly less likely to go to a grammar school,” according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

The IFS said the question remains whether this is because poorer children are less likely to apply or less likely to get in once they apply.

For example, the cost of sending a child further away to go to grammar school can discourage parents from getting their children to apply, the Sutton Trust has found.

Some grammar schools are now prioritising lower income students through policies such as quotas, offering places to children with lower scores on the 11+ exam, or changing the priority rules for when they are oversubscribed.

Professor Vignoles from the University of Cambridge told the BBC, “Whilst quotas or other measures might help, the fundamental problem in the system is the very large gap in achievement between free school meals pupils, and others, at the end of primary school."

The government has said it will look into admissions arrangements in its plans for new grammar schools. It also wants to find ways for new grammars to support other local pupils in non-selective schools.

We can’t be sure if poorer pupils going to grammar schools do particularly better

Pupils eligible for free school meals who attend grammar schools do better academically than their peers who do not attend selective schools.

The Education Policy Institute (EPI) estimate that these pupils might gain around half a grade for each subject at GCSE from the benefit of attending a grammar school—more than for pupils not eligible for free school meals.

Poorer pupils who attend grammar schools are also more likely to achieve to the same level as their more advantaged classmates. For example, the Conservatives have previously claimed that the attainment gap between disadvantaged and non-disadvantaged students in grammar schools is “virtually zero”.

It’s closer to zero (but not quite zero).

But, neither of these may tell us very much about the added value of grammar schools. To get into grammar schools children mostly have to be high achievers anyway, and some reports have suggested accounting for this removes much of the difference.

The comparison may also be affected by the small numbers of pupils in grammar schools, the EPI said.

Adjusting for pupil characteristics, research published by the Sutton Trust in 2008 found that “pupils eligible for FSM [free school meals] appear to suffer marginally less educational disadvantage if they attend grammar schools”.

But it said the effect wasn’t completely clear cut because there could well be further differences between grammar school pupils and their peers not accounted for in the study.

Overall grammar schools do seem to be good for those who go

Overall, attending a grammar school does seem to be good for your educational attainment and earnings later in life, according to the IFS.

It cites two academic studies on children born in the 1950s as evidence that “attending a grammar school is good for the attainment and later earnings of those who get in”.

But it goes on to say “there is equally good evidence that those in selective areas who don’t pass the eleven plus do worse than they would have done in a comprehensive system”.

That’s the same for Northern Ireland, according to the IFS. It examined the evidence from the expansion of grammar schools in Northern Ireland in the late 1980s. Average performance in Northern Ireland improved, it said, but the gap between the top performers and the low performers widened, with pupils not going to grammar schools doing worse.

Poorer pupils who don’t go to grammars seem to do worse

The attainment gap (specifically the number of pupils who attain 5 or more A*-C GCSEs) between children eligible for free school meals and their peers is about 6% wider in wholly selective areas than across the country as a whole, according to the Education Policy Institute.

It says this isn’t surprising, because grammar schools will attract more high achievers who aren’t eligible for free school meals from other areas, creating a disproportionate number of non-disadvantaged pupils who will do well.

But it also found that, “in areas with a high level of selection, pupils eligible for free school meals who did not attend grammar schools achieved 1.2 grades lower on average across all GCSE subjects.”

“There is repeated evidence that any appearance of advantage for those attending selective schools is outweighed by the disadvantage for those who do not”, says Professor Stephen Gorard of Durham University. “More children lose out than gain, and the attainment gaps between highest and lowest and between richest and poorest are larger”.

Similarly, Luke Sibieta at the IFS says that grammars "seem to offer an opportunity to improve and stretch the brightest pupils, but seem likely to come at the cost of increasing inequality".