Spending on schools in England

Day to day funding for schools per pupil stayed at roughly the same level from 2010/11 to 2015/16, once rising prices are taken into account.

After that, funding per pupil fell and since 2017/18 it has flattened out. Funding from 2017/18 to 2019/20 remains lower than 2015 levels.

New funding reforms underway should share out the available funding more consistently through a National Funding Formula (NFF). The NFF itself won’t change the size of the total schools budget, but will mean some schools get more funding, and some schools get less funding.

A full roll out of these reforms has been put on hold until at least 2020/21.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

The schools budget: how much money is there?

The schools budget for pupils aged 5-16 in England is expected to be nearly £39 billion for 2017/18. A further £3 billion is being spent on early years provision.

This £39 billion is about 58% of total government education spending in England, and 12% of total public service spending in the UK for 2017/18.

The government has said that school funding is at “record levels”. This is correct in terms of how many pounds are in the budget, but inflation and increasing pupil numbers mean per-pupil funding has fallen since 2015.

Between 2010 and 2015, spending per pupil had stayed largely the same, according to economists at the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS).

Funding was expected to fall from then up to 2019/20, but in 2017 the government announced an additional £1.3 billion for the schools budget between 2017/18 and 2019/20.

This means that school spending per pupil will still be less than it was in 2015/16, but instead of continuing to fall between 2017/18 and 2019/20 it will stay roughly the same per pupil, according to the IFS.

This additional money for schools comes entirely from other areas in the education budget, the government has said. For example, £420 million has come from the budget used to repair and fund school buildings, and £280 million has come from the budget for new free schools.

How the school funding system works

State-funded schools fall into two main groups: maintained schools, where funding and oversight is through local authorities, and academies, where funding and oversight is from the Department for Education. Free schools are a type of academy.

Around 24% of all primary school pupils and 69% of all secondary school pupils studied in academies in 2017.

Up until recently, the government has decided how much of the budget to hand over to each local authority, largely based on how much each authority has received per pupil in previous years. Each local authority then uses a local funding formula to share this money out to local schools. They take into account several factors such as pupil numbers, deprivation, and prior attainment.

Although outside of the control of local authorities, the money used to fund academies and free schools is still calculated using the local funding formulas.

The old funding system has been widely seen as flawed

The IFS, the Education Policy Institute (EPI) think tank, the government, and others have all said the old funding system is flawed and awards money inconsistently.

Part of this is intentional, the IFS has said, because of deliberate choices by the government to target funding towards disadvantaged schools and areas with higher costs.

But some variation has been more unintentional.

The IFS has said “funding levels have become increasingly divorced from the reality of what local authorities look like today” because the money going to each local authority has been largely based on what they were like in the early 2000s.

This has meant that there is wide variation in funding per pupil across similar schools in England. One example the IFS gave is that:

“Plymouth and Bradford have similar characteristics (e.g. both have about 17% of pupils eligible for free school meals), but funding per pupil is around £500 higher in Bradford than it is in Plymouth. This is largely because back in 2004 there was a significant gap, with about 24% of pupils eligible for free school meals in Bradford and 16% in Plymouth in 2004.”

It also said that different local authorities making different choices over how to allocate school funding can mean that similar schools receive different levels of funding.

The schools funding system is changing from 152 local formulas to one nationwide formula

The government is introducing a new funding system which aims to take into account similar factors to the local funding formulas, but replace the 152 local formulas with a single National Funding Formula (NFF).

It applies to maintained schools, academies, and free schools, and recalculates the core funding that schools receive from the government for pupils aged 5-16.

The reforms aim to make the system more transparent, more uniform, and use an up-to-date assessment of need.

The NFF was initially supposed to come into full force from 2019/20 but now the government has announced plans which suggest it won’t be implemented in full until 2020/21 at the earliest.

The National Funding Formula has a complicated outcome on budgets depending on the kind of school

Both the IFS and the EPI have said that the new formula will inevitably create ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ in terms of who receives better or worse funding.

The IFS has said that the proposed formula largely preserves the intentional variation under the old system where certain types of schools or areas receive better funding. But the intention is to ensure that similar schools receive similar funding.

Both of their analyses were done before the government made further funding announcements in September 2017 designed to ease transition to the new formula, so the exact picture may change.

Although the funding changes are calculated on a school-by-school basis, one broad implication from the pre-September IFS analysis is that the biggest losers will be schools in Inner London. They currently receive the highest funding per pupil.

The EPI found that “the most disadvantaged primary and secondary schools in London are expected to see an overall loss of around £16.1m by 2019/20”.

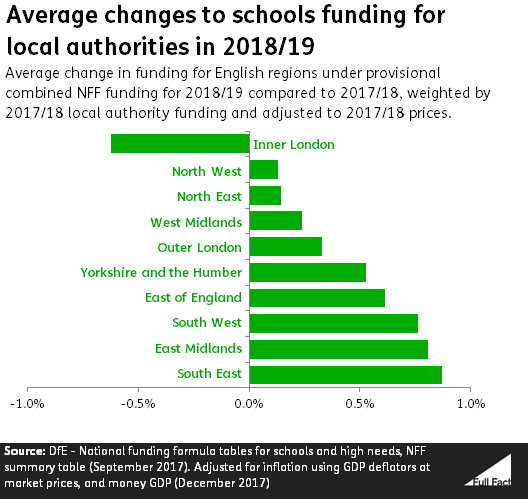

Updated figures released by the Department for Education in September suggest Inner London local authorities will still see the biggest losses on average.

Both the IFS and the EPI’s analysis suggest that about one in three local authorities would see a decline in overall funding for their schools through the NFF.

A transitional period of ‘soft’ NFF has been introduced

In July 2017, the government announced that instead of a complete ‘hard’ roll out of reforms, a transitional ‘soft’ rollout of the NFF would take place from 2018/19 to 2019/20.

This transitional ‘soft’ version of the NFF calculates what each school would receive under the ‘hard’ NFF. It then applies certain transitional rules—for example, there is a protective cap so every school’s notional funding increases by at least 0.5% per pupil in cash terms during 2018/19.

The government then adds the school budgets together for each local authority and hands the money over to them.

The local authorities then still divide the money up under their own terms, and so will set each school’s budget for the next two years. They can reduce a school’s budget for the year by up to 1.5% per pupil, if they wish.

So this reduces any sudden changes to a school’s budget but means schools have to wait longer for funding to become more consistent (although some of the transitional rules seek to address this).

We don’t know what government plans are for school funding after 2019/20, although the government says it intends to introduce the hard NFF formula.

This spreadsheet from the Department for Education shows how a hypothetical full NFF roll this year would affect each school’s cash budget.

Correction 12 February 2018

We changed a typo in the graph accompanying this article. It read "South Wales" instead of "South West".

Correction 26 April 2018

We added "per pupil" to the sentence "This means that school spending per pupil will still be less than it was in 2015/16...".