“The new licences issued today will take the number of badgers killed in the cull to an astonishing 130,000… This is despite official data showing that incidents of bovine TB increased dramatically in areas of Gloucestershire despite the cull.”

Sue Hayman MP, 11 September 2019

Since 2013, the government has permitted the culling of badgers across certain parts of England. The aim of culling is to control the spread of tuberculosis among cattle (bovine TB) as badgers carry the disease.

Last week, Labour MP and shadow Defra secretary Sue Hayman argued that the government’s granting of new culling licenses would take the total number of badgers killed to 130,000—despite evidence that incidents of bovine TB have increased in one cull area in Gloucestershire.

It’s correct that if the maximum permitted number of badgers were culled this year, it would take the tally to 130,000 since 2013 (when the first culling trials took place). In practice, it’s unlikely that the maximum number will be culled.

It’s hard to tell yet what impact badger culling is having, because it has only been going in for two years or fewer in most areas. That said, there has been little discernible decrease in bovine TB so far, and wider research suggests that its impact is at best limited.

However, while the specific evidence cited by Ms Hayman about increased bovine TB in Gloucestershire is correct, it’s not very meaningful because it only looks at a one-year change in one particular area of Gloucestershire. The impact of badger culling needs to be assessed over a longer time period and wider geographical area.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

How many badgers have been culled?

Between 2013 and 2018, almost 67,000 badgers were culled.

The government has just announced that 40 “badger control areas” have been granted licenses for 2019. These licenses designate where badger culling can take place, and how many can be culled in each area.

Overall, the licenses allow for the culling of a maximum of 63,000 badgers across the 40 control areas. The minimum target is 37,000.

If the minimum number of badgers were culled this year, it would bring the total to almost 104,000 since 2013. If the maximum target number were culled, it would bring the total to 130,000.

In previous years the number of badgers culled has tended to be roughly halfway between the minimum and the maximum numbers. The maximum threshold has never been reached.

The number of badgers culled has been increasing year-on-year. Last year, almost 33,000 badgers were culled across 30 areas, and the year before that it was 19,000 in 21 areas.

Is bovine TB surging despite the cull?

Ms Hayman argued that culling is ineffective, pointing out that “incidents of bovine TB increased dramatically in areas of Gloucestershire despite the cull”.

The Labour Party confirmed this referred to figures calculated by a group of scientists including veterinary surgeon Dr Iain McGill, using data they obtained from the government via a freedom of information request, which we have seen.

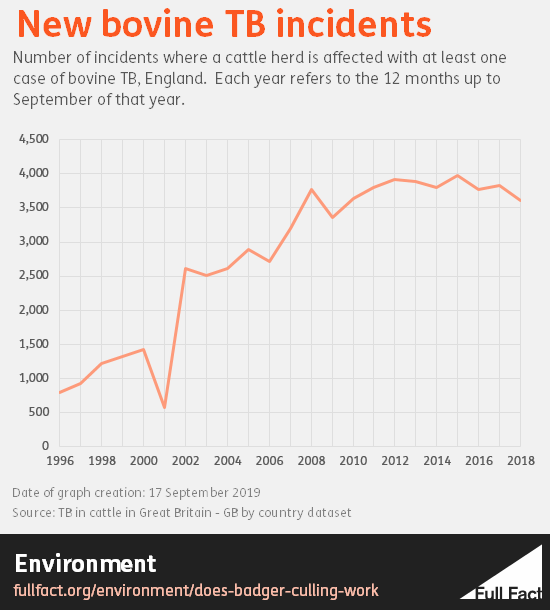

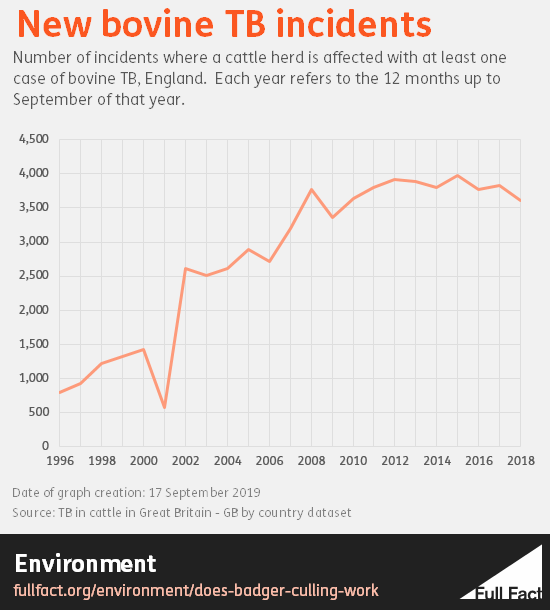

They found the number of new “herd incidents”—where herds of cattle are affected with at least one case of bovine TB confirmed by a post-mortem test—increased by 130% in a part of Gloucestershire between 2017 and 2018.

In 2017, 10 new herds had their official TB-free status withdrawn. In 2018, 23 new herds had this status withdrawn.

However, we should be careful of reading too much into this increase of 130% over a single year in a specific part of Gloucestershire. As the BBC points out, you need to look over the longer term to get a fuller picture of the impact of culling, as there could be a spike in outbreaks in a single area in a single year.

What is the broader picture?

Ultimately it’s hard to tell yet whether badger culling is having a significant effect in reducing the spread of bovine TB.

That’s because research suggests badger culling is only likely to be effective if sustained over large areas for several years. However, only two cull areas have been in operation for more than three years—in Gloucestershire and Somerset.

In the Gloucestershire area, there were slightly more “new herd incidents” of TB in the year to September 2018 than in the last year before culling began (2012). In the Somerset area there were fewer.

The number of new herd incidents is one of two key measures used by the government for understanding the impact of badger culling, as it can tell us if culling stops the immediate spread of bovine TB.

Since culling came into operation in England, the number of new herd incidents of bovine TB is down slightly across the country as a whole.

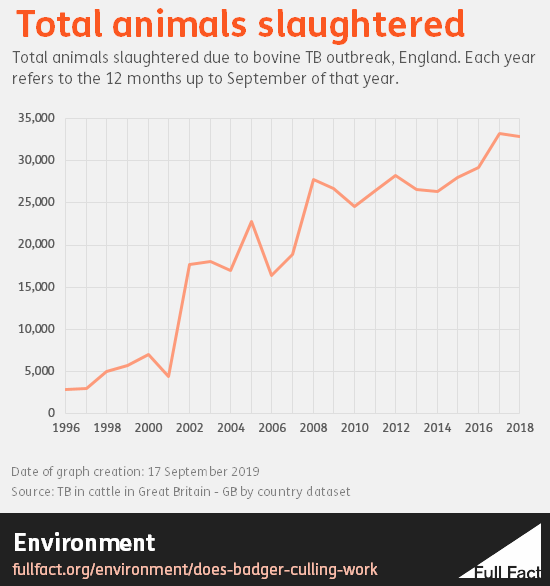

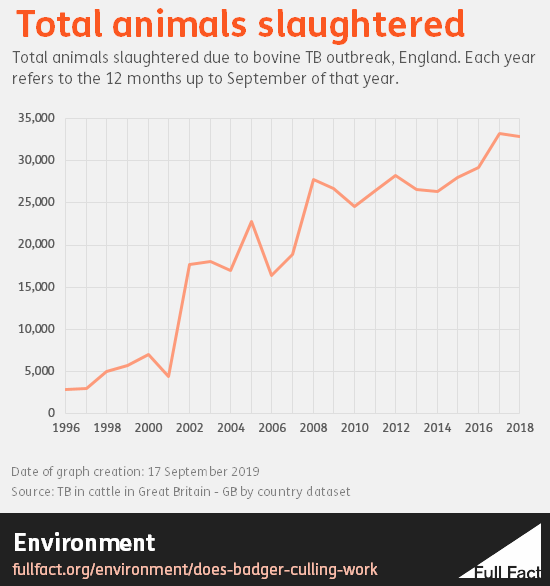

The number of cattle slaughtered as a result of a bovine TB outbreak is higher than it was before badger culling started, although it fell from 2017 to 2018. Defra puts this increase down to “better testing, particularly in herds known to have been infected previously”, according to the House of Commons Library.

We can also look at the “prevalence” of TB, rather than new herd incidents. This tells us how many herds have a case of bovine TB overall, rather than the number that have been newly infected in a given year. 6% of herds in England had a bovine TB case in 2018, which is roughly the same level it has been at since 2011 (it was lower before then).

The overall prevalence can be affected by factors other than badger culling—such as how long it takes to remove diseases from infected farms.

What does wider evidence show?

We perhaps shouldn’t expect any culling efforts to lead to a significant drop in bovine TB levels overall.

Most of the evidence on the effectiveness of badger culling in the UK goes back to the “Krebs trials” which ran from 1998 to 2005. This found the ultimate impact of culling to be limited at best.

The interim conclusions from these trials found that proactive culling (where as many badgers as possible are culled, and not only in response to TB outbreaks) reduced the incidence of bovine TB by 19% within the cull area, but increased it by 29% up to 2km outside the cull area. This has been linked to the observation that culling disrupts badgers’ territorial behaviour.

A 2007 report for the government by the Independent Scientific Group concluded that “overall benefits of proactive culling were modest… and were realised only after coordinated and sustained effort… Given its high costs and low benefits we therefore conclude that badger culling is unlikely to contribute usefully to the control of cattle TB in Britain, and recommend that TB control efforts focus on measures other than badger culling”

The findings were contested by the government’s chief scientific adviser, Professor David King, who argued that badger culling was the best option available, but needed to be in a large area and sustained over time.

Based on evidence from both parties, the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs Select Committee concluded that “there might be an overall beneficial effect” as a “contribution” to reducing bovine TB levels, if carried out under the terms suggested by Professor King and others made by the Independent Scientific Group. However, the committee said there was “significant risk” these standards would not be met, and did not specify how far it could go to reducing bovine TB.

In 2008, the Labour government decided not to introduce a badger cull, and instead prioritise the vaccination of badgers, in light of the findings of the 2007 report.

In 2011, the Coalition government announced its intention to introduce a policy of badger culling in England to combat the spread of bovine TB. The government has cited the Krebs trials organised by the previous Labour government as the basis for its decision to introduce culling.