26 May's BBC Question Time, factchecked

On the Question Time panel last night were Ed Miliband, David Davis, Caroline Lucas, Dreda Say Mitchell and Steve Hilton. We've checked their claims on trade with other EU countries and the Commonwealth, young people's attitudes to the EU, and immigration.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

The UK's negotiating power

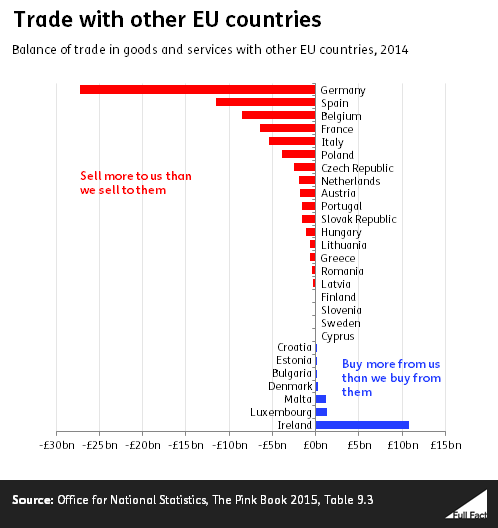

“All of these countries have a vested interest [in negotiating with us]... Poland wants to sell machinery to us. The Italians want to sell fashion goods to us. The Germans, cars and engineering goods. The Spaniards and French want to sell food and drink to us. And they all have surpluses in our direction. So they want to sell to us more than we want to sell to them.”—David Davis MP

It’s correct that these countries sell more to us than we sell to them.

These figures are unreliable and can differ depending on whether you’re using UK reported data or data reported from other EU countries. Here we’re using UK reported trade.

“You keep saying that the EU needs us more than we need it. Our exports to the EU are 13% of our GDP. EU exports to Britain are 3% of their GDP. We actually need them more than they need us.”—Caroline Lucas MP

As with the previous claim, it’s difficult to get a single answer for the size of the UK’s exports and imports to and from the rest of the EU.

Using UK data, exports of goods and services to other EU countries were worth £230 billion in 2014—about 13% of the value of the British economy.

Newer figures are now available, showing it’s down to 12% for 2015. It’s stayed at around 13-15% over the past decade.

In 2014 exports from the rest of the EU to the UK were worth between £290 and £360 billion, depending on whether you use EU data or UK data. That’s about 3 to 4% of the size of the remaining EU’s economy. There aren’t figures available for 2015.

As explored above, our trade with other EU countries can vary significantly.

Update 29 May 2016: This section originally said "In 2014 exports from the rest of the EU to the UK were worth between £290 and £360 trillion" where it now says billion. We are very sorry for the error.

Young people’s attitudes

“Young people like the freedom to travel...”—Ed Miliband MP

“Which young people are we talking about? That is my problem sometimes. Sometimes we use the term young people, we’re invariably talking about young people who are students, who are part of the professional class.”—Dreda Say Mitchell

“No, no we’re not talking about that…”—Ed Miliband MP

Young people are, overall, much more likely to want to stay in the EU than older people. Analysis by NatCen Social Research found 18-34 year olds were most likely to say they would vote to remain, while those aged 55 and over were least likely to do so.

They’re also more likely to have had a university education than older people, so the university educated are more likely to be represented among younger age groups.

Looking at all ages, there is evidence that those with lower levels of educational qualifications are less likely to want to stay in the EU.

So it’s likely that young people with a lower educational background are comparatively less keen on staying in the EU than their university graduate peers. We weren’t able to get hold of data which gives us a precise breakdown on this.

Trade and the Commonwealth

“One thing, Mr Miliband, that you seem to be forgetting is we have the Commonwealth, which is now a bigger trading bloc than the European Union”—Audience member

The Commonwealth, a club of mostly former British colonies, is not a trading bloc. While its 53 members trade with one another, there is no free trade agreement linking them all together.

“Conventional thinking among trade policy experts and policy makers suggests that a free trade area of the Commonwealth would be an utter impossibility for legal and political reasons”, according to a 2013 report for the International Trade Centre.

Professor Steve Peers of the University of Essex has said that while the UK ended special trade ties with the Commonwealth when it joined the EU in 1973, the EU has since put in place or started negotiating trade agreements with 90% of Commonwealth countries.

If we left the EU, we would be free to negotiate free trade agreements with countries outside, which currently we can’t do as an EU member. Some Leave campaigners argue that we would be able to capitalise on “shared history, cultural links, common legal systems, business practices, and much more” between the UK and the rest of the Commonwealth.

The Commonwealth isn’t (yet) a bigger market than the EU. The economies of its members were worth around $10 trillion in 2015, according to the IMF, while the EU was worth $16 trillion.

In 2011, the Commonwealth took 10% of UK goods exports and 12% of services exports, according to estimates from the House of Commons Library. The EU took 54% and 41% in that same year—although the proportion has declined whereas exports to the Commonwealth have increased (at least up until 2011, when the data goes up to).

EU in world economy

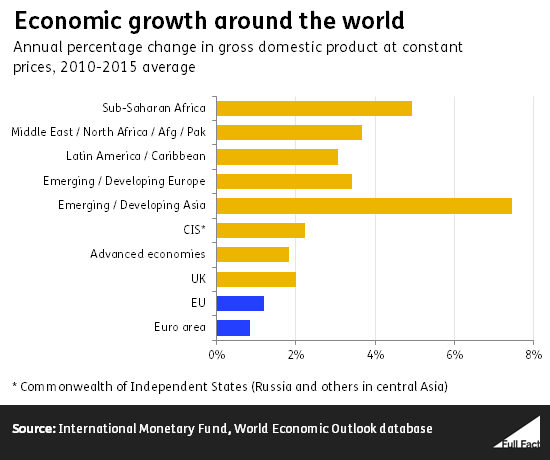

“The EU right now, for example, is one of the worst performing economic areas in the world, it’s basically a sinking ship economically.”—Steve Hilton

This claim really depends on what you mean by an ‘economic area’, and what you measure, but Mr Hilton has a point.

We looked at IMF data for economic growth over the past five years, measured in gross domestic product (GDP) and broken down into regional country groups. It shows that the EU, and the eurozone within it, grew more slowly than other regions.

In most cases it was starting from a better position, as a rich area, but it also grew more slowly than what the IMF considers ‘advanced economies’ generally.

That doesn’t make it a ‘sinking ship’ as such—the EU economy is still growing. The decline is relative to other parts of the world.

EU immigrants and the economy

“We know from official figures that people who come here from the EU contribute about £2.5 billion more, in terms of taxes than they claim in benefits”—Ed Miliband

Figures from HM Revenue and Customs found that, in 2013/14, recently-arrived EU nationals contributed £2.5 billion more in income tax and NI contributions than they took out in tax credits and Child Benefit.

The HMRC source wrongly labels this as the “total net fiscal contribution” of this group. This isn’t the whole picture.

It’s just looking at benefits administered by HMRC, and doesn’t include payments like Jobseekers’ Allowance and other benefits that are managed by the Department for Work and Pensions, some of which we’ve previously analysed in this context.

The HMRC figure is also just looking at EU immigrants who arrived between 2010 and 2014. Ed Miliband didn’t specify recent arrivals from the EU, and research has suggested those who’ve been here for longer are likely to have made a lower or negative recent contribution to the overall public finances.

There’s no single correct figure for what EU immigrants contribute to or take away from the overall public finances.

Correction

During Question Time we tweeted in response to this claim that there aren’t official figures showing immigrants help the economy. This wasn’t correct and didn’t address what Mr Miliband said.

Official figures from the Office for Budget Responsibility suggest higher net migration would reduce pressure on government debt over a 50-year period. Research generally suggests that the impact of immigration on the public finances in the UK is relatively small. See our full briefing on how immigrants affect public finances.