“The Chequers deal is now more unpopular with the British people than the Poll Tax was.”

Justine Greening MP, 3 September 2018

“The Prime Minister’s Chequers plan is even more unpopular than the Poll Tax.”

Ian Blackford MP, 5 September 2018

In recent days politicians from several parties have said that the so-called ‘Chequers deal’—the current cabinet-endorsed negotiating position on Brexit—is less popular than the ‘Poll Tax’, the widely-protested tax introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s government.

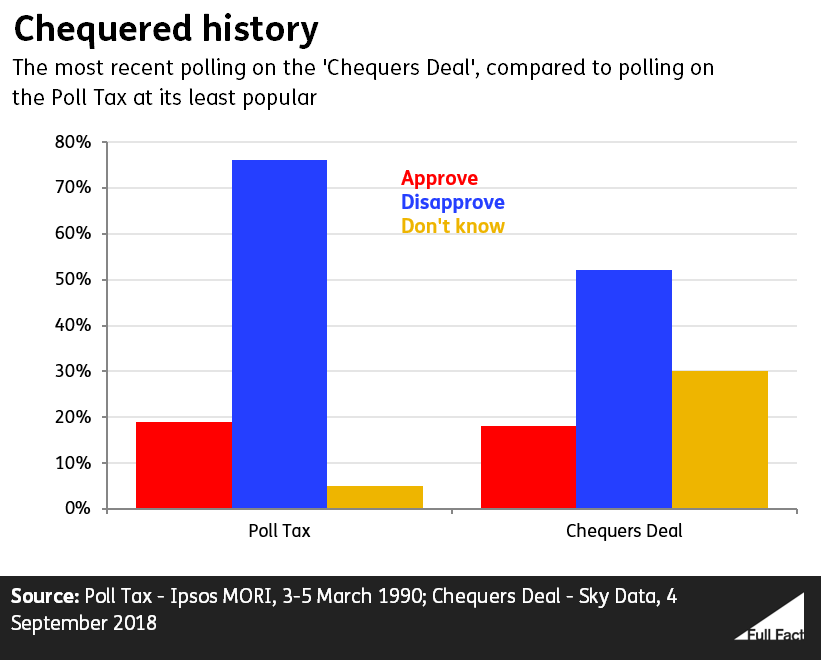

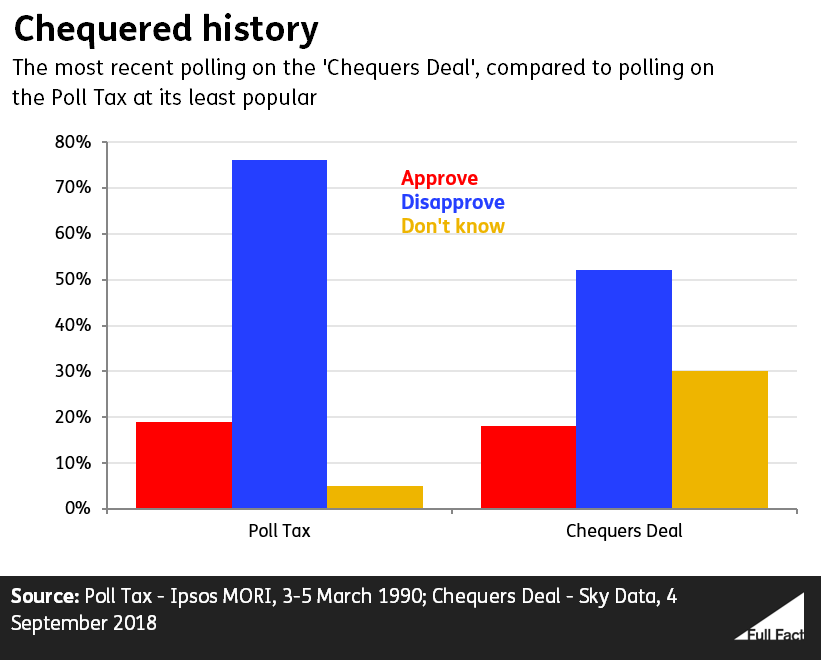

It’s true that, according to recent polls, the percentage of people who say they support the Chequers deal (18%) is lower than the percentage who supported the Poll Tax at its least popular (19%), although based on a poll that’s such a small difference we can’t know for sure that Chequers has smaller support levels.

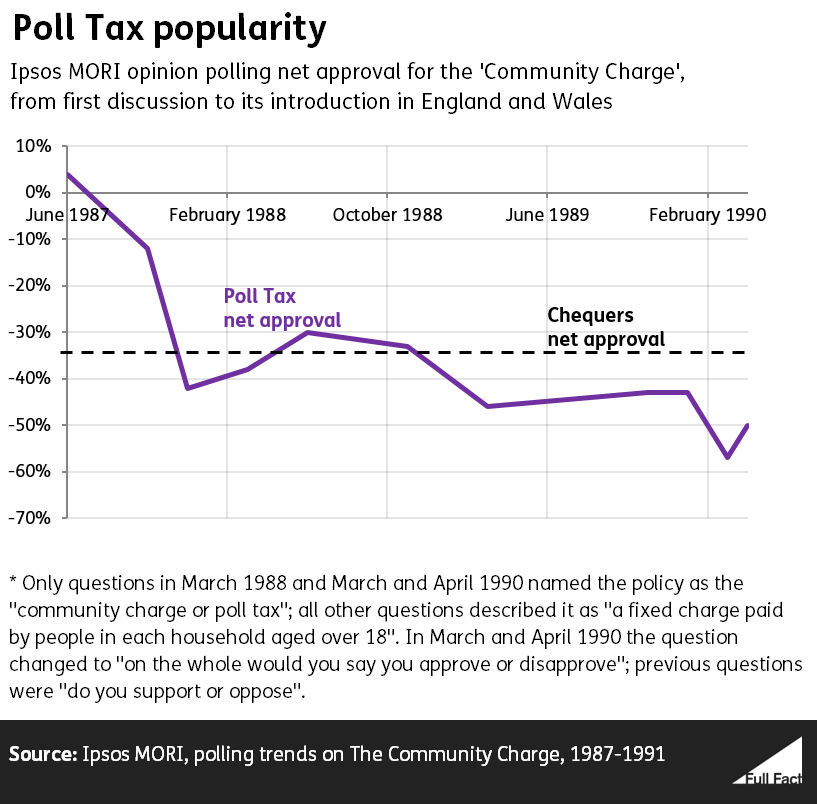

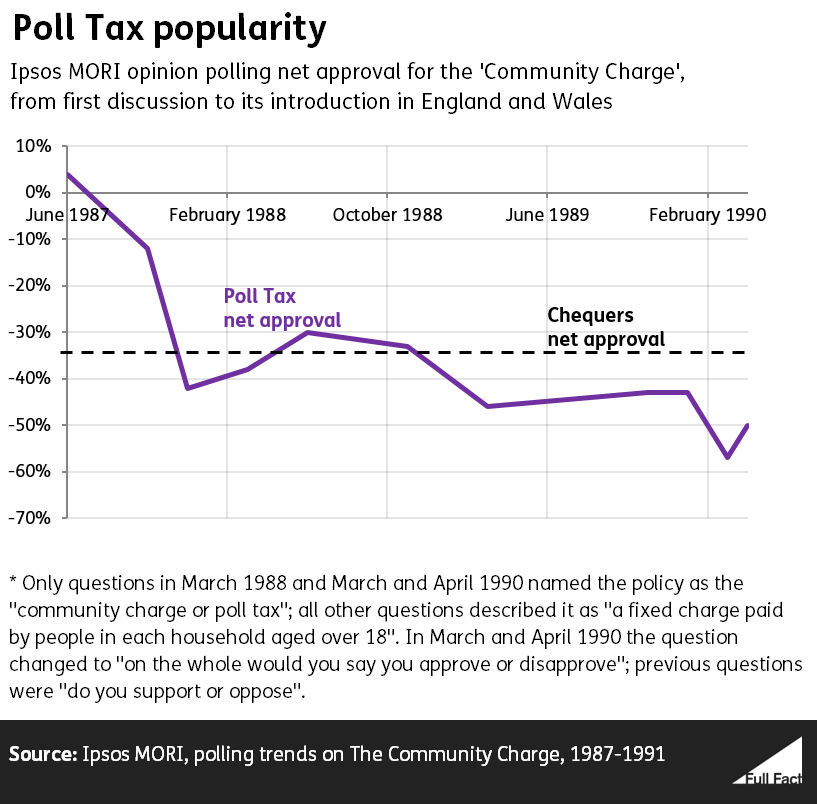

The most common way of measuring popularity, however, is to look at the difference between positive and negative opinions. By this measure, the Poll Tax (with a net approval of -57% at its least popular) was far more unpopular than the Chequers deal (net approval -34%), as many more people actively opposed it. A large percentage of people say they don’t know what they think of the Chequers deal.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

What was the Poll Tax?

The ‘Poll Tax’ – officially known as the ‘Community Charge’ – was a new local government flat tax introduced by Margaret Thatcher’s Conservative government, to replace the previous system of council ‘rates’. It came into force in Scotland at the beginning of the 1989 financial year, and then in England and Wales a year later in 1990.

The tax was extremely unpopular, sparking widespread protests, riots and co-ordinated non-payment campaigns. Opposition to the tax (and the damage it was having on Conservative polling figures) was a major factor the leadership challenge that forced Margaret Thatcher to resign in November 1990.

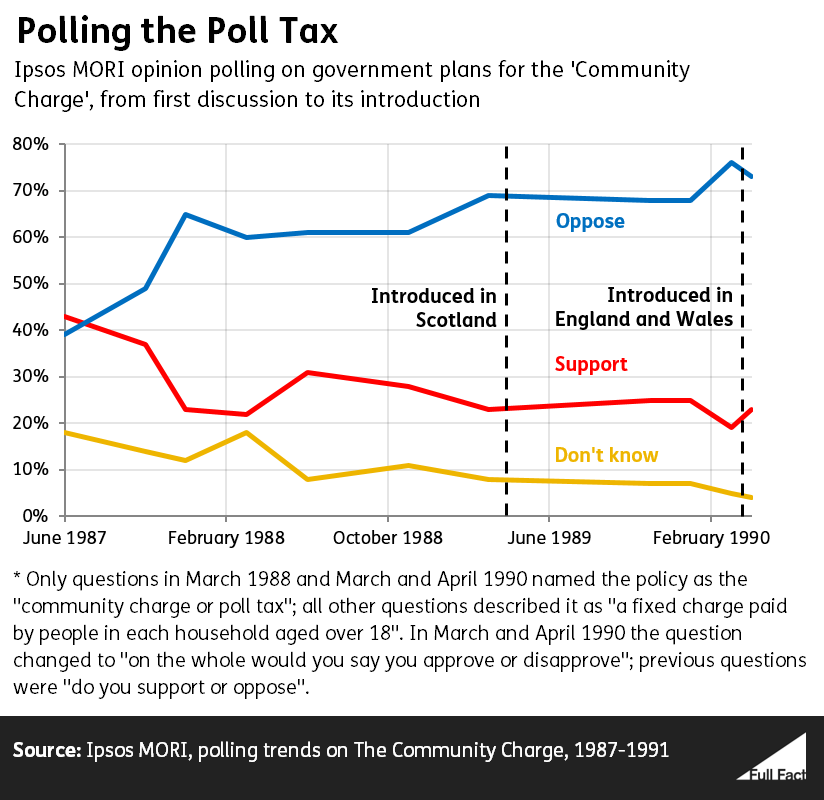

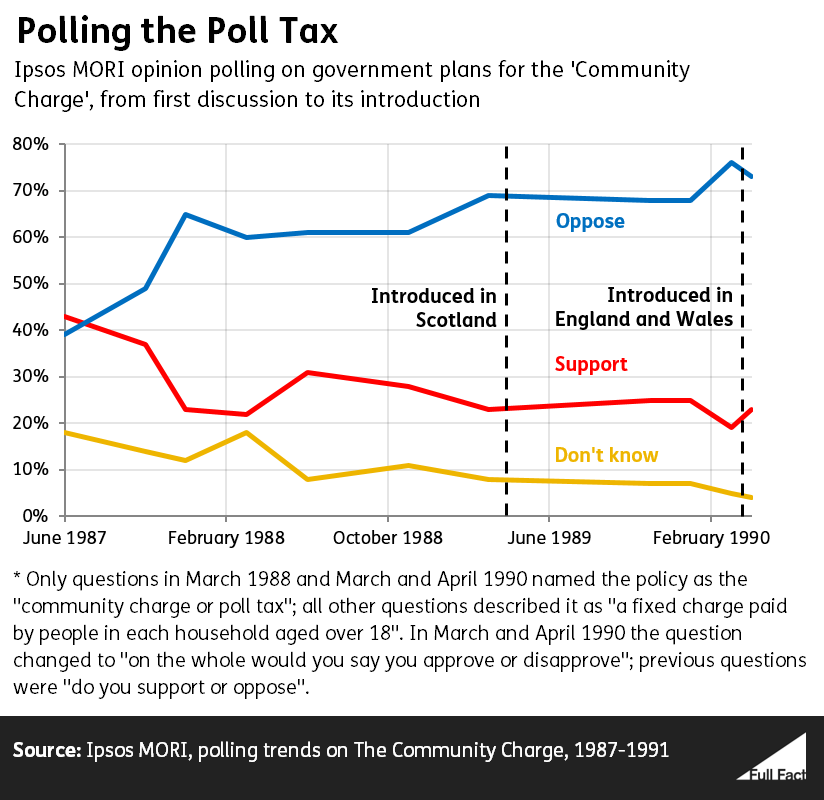

Polling firm Ipsos MORI has historical opinion poll figures covering several years from when the Poll Tax was first proposed, until its introduction in England and Wales in the spring of 1990. This data shows that opposition to the tax peaked in March 1990, shortly before it was due to come into force in England and Wales, when only 19% of people approved of it and 76% disapproved, a net approval of -57%.

How does the Chequers deal compare?

The ‘Chequers deal’ or ‘Chequers plan’ is the common term for the Brexit negotiating position agreed by the cabinet during a meeting at Chequers (the prime minister’s country residence) in early July. It was immediately controversial, and prompted the resignation of several pro-Brexit cabinet ministers who opposed it, including the Foreign Secretary and the Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union.

A poll by Sky Data on September 4 found that 18% of people approved of the deal, while 52% disapproved (with 30% responding ‘don’t know’). Earlier polling by YouGov, which asked a slightly different question, showed that only 13% of people thought the deal would be “good for Britain” compared to 42% who thought it would “not be good for Britain” (44% responded ‘don’t know’).

Here we’ll use the Sky Data figures, both because they are the most recent, and because the question they asked is most comparable to that asked about the Poll Tax.

While the level of support for the Chequers deal is marginally below that of the Poll Tax (although within the polling margin of error), the level of opposition to it is significantly lower, by 24%. This is reflected in the fact that the percentage of ‘don’t knows’ is far higher for the Chequers deal, at 30% compared to just 5% for the Poll Tax.

This means that the net approval for the Poll Tax at its worst was -57%, while that for the Chequers Deal is -34%. Over the years that Ipsos MORI polled, the Poll Tax regularly had net approval ratings below the current level for the Chequers deal. So while the low level of support for the Chequers deal is comparable to the Poll Tax at its least popular, it’s not accurate to say that it is “more unpopular”.

When considering the number of ‘don’t know’ responses, it’s worth noting that with the Poll Tax the proportion of ‘don’t knows’ decreased as the policy came closer to being implemented.

It’s also worth noting that people can dislike the Chequers deal for opposing reasons: some Leave supporters think the form of Brexit it proposes is too ‘soft’, while Remain supporters may oppose it because it is still a plan for Brexit.