The Prime Minister has pledged an extra £20 billion in funding for the NHS in England by 2023/24, saying this will in part be paid for by the ‘Brexit dividend’.

There is no guaranteed extra money—or ‘Brexit dividend’—as a result of the UK ceasing its contributions to the EU budget after leaving. Other costs associated with leaving are expected to more than offset that saving.

The government also won’t know what the impact of Brexit will be on the public finances until it finalises a deal with the EU.

Any extra funding given to the NHS or any other part of public spending would then need to come from increased taxes (as the Prime Minister also alludes to), increased borrowing, or reducing spending on something else. We’ve looked at the NHS funding pledge in more detail here.

The Health Secretary has also said that if there was any Brexit dividend then any savings “won’t be anything like enough” to fund the NHS commitment.

Savings from EU budget contributions

The UK currently pays between £13 and £14 billion into the EU budget every year—that’s roughly £250 to £280 million a week. It also gets some of that back, mainly through payments to farmers and for poorer areas of the country such as Wales and Cornwall. Those are worth about £4 billion a year or £75 million a week.

The government has already indicated that, until at least 2022, it will continue to spend some money on the areas where the EU currently gives us funding. It may also wish to participate in EU agencies and programmes after Brexit, which could come at a price.

That could mean, when we stop paying to the EU budget in 2021, we’d be likely to have at least £9 to £10 billion a year—our ‘net payment’ to the EU budget—which is worth £170 to £190 million a week. This is the dividend the Prime Minister is referring to.

That would be a saving in itself, but it’s not extra money. “There isn't a Brexit dividend” according to Paul Johnson, director of the Institute for Fiscal Studies. That’s because the short-term savings from ending payments to the EU budget are expected to be outweighed by the costs elsewhere.

Not all of the costs are certain yet, so we don’t know what the exact change to the public finances will be. Some though, such as the ‘divorce bill’, have already been agreed in principle.

Costs from the ‘divorce bill’

The UK hasn’t left the EU yet, so for now we’re continuing to pay into the EU budget, and will do so until we leave fully, which is currently expected to by 2021. We’re also likely to be paying a ‘divorce bill’ for leaving.

The ‘divorce bill’ is a sum agreed by the UK and EU which settles the UK’s financial commitments or outstanding liabilities, like EU pensions.

The latest estimate for that figure is around £37 billion in total, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility. Between 2021 and 2028, about half of that—£18 billion—is expected to be due.

Costs from the economic effects of Brexit

Eventually those divorce bill payments will drop off, but there’s still the question over the wider economic impact Brexit will have and how this affects the public finances.

No one knows exactly what the economic impact of Brexit will eventually amount to, but the government has already accepted, through the Office for Budget Responsibility, that the public finances have taken a hit.

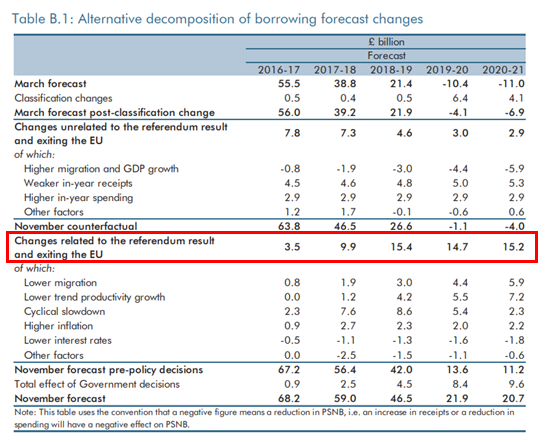

Estimates from 2016, just after the referendum, suggest the economic effects of Brexit “weakened the public finance by £15 billion per year by the early 2020s, more than outweighing the UK’s £8 billion net contribution”, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

As the IFS also said in January, “In other words, so far the implication is that Brexit has reduced rather than increased the funds available for the NHS (and other public services), both in the short and long term…

“Although subsequent growth after the OBR’s forecast has been slightly stronger than expected, the medium-term outlook is now gloomier than in November 2016.”

In other words, at the moment the cost of Brexit is expected to outweigh any ‘dividend’ the UK gets from ending payments to the EU budget.

We don’t know what deal the UK will ultimately strike with the EU upon leaving, so the eventual impact on the public finances is still uncertain.

Downing Street on Twitter,

Downing Street on Twitter,