'Freedom of panorama', as a rallying cry, sounds like something you'd hear shouted on a BBC picket line by investigative journalists. It turns out to be something far more familiar: the right of people to publish—whether or not for profit—photographs of landmark buildings or public art.

Claims that this is under threat at European Union level are accurate up to a point. Restrictions on the commercial use of such images have been suggested by a committee, but it's a long way from that to a new law.

Copyrighting a building?

In 2002, the US Postal Service released a stamp featuring a photograph of the Korean War Veterans Memorial sculpture in Washington, D.C.. This was protected by copyright law, which stops creative products from being reproduced by others without the permission of the creator—which hadn't been granted. The sculptor sued both the photographer and the Postal Service; and he won.

That couldn't happen here because, as every tourist presumably knows, section 62 of the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 creates an exception to normal copyright rules when it comes to buildings and sculptures "if permanently situated in a public place or in premises open to the public".

This means that you can take a picture of something like London's Gherkin, show your friends and even sell prints without worrying about being in breach of the architect's copyright in the building.

EU law currently allows for freedom of panorama

EU rules on copyright currently allow for exceptions like this. But not all member states have them. Notoriously, pictures of the Eiffel Tower lit up at night are subject to copyright, but not photographs taken during the day.

What's now been proposed is for 'freedom of panorama' to be restricted when it comes to commercial use of photos or videos.

It's not intended to catch personal photographs. But campaigners argue that social media blurs an already tricky distinction between commercial and non-commercial use. Uploading your Gherkin picture to Facebook, for instance, means it can used by Facebook under the terms of a "royalty-free, worldwide license" that you grant the company when you sign up. If a social network managed to make money from your picture, it's possible that an aggrieved architect could seek damages for breach of copyright in the absence of freedom of panorama protections.

If that's true, though, it's already true in countries like France that don't have freedom of panorama. French social media users sharing those night-time pictures of the Eiffel Tower could technically be in breach of French copyright law.

An amendment to a report isn't a diktat from Brussels

This is a long way from becoming law. It's gone into a draft report by the European Parliament on EU copyright rules. The MEP coordinating this report describes it as "not a draft law".

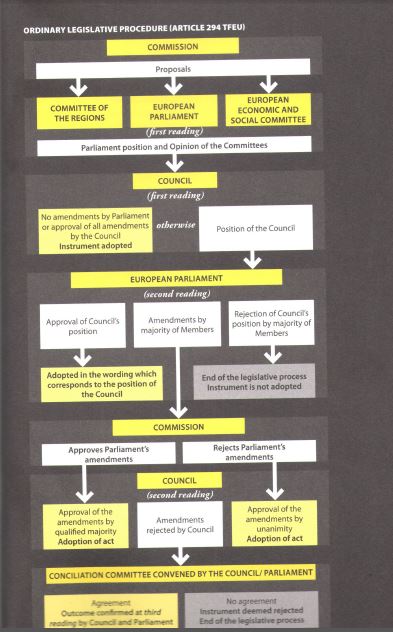

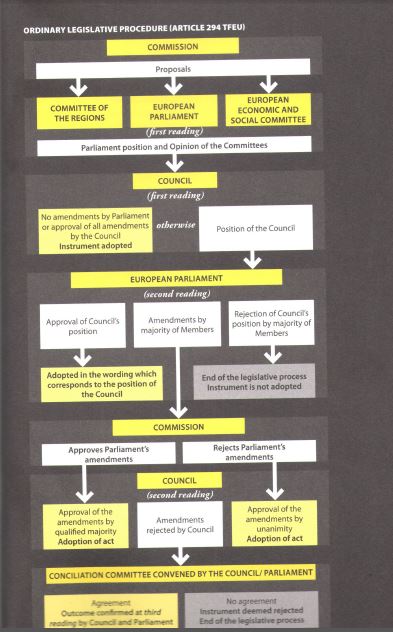

Put another way, this model of simplicity is the European Union's ordinary procedure for making laws. The proposal on freedom of panorama isn't even on the diagram yet, and may never be.

The European Commission, not the Parliament, has the exclusive right to propose new EU legislation. It might take this suggestion on board in drawing up a new copyright regime, due to be published by the end of this year. Equally, it might not. The European Parliament, even if it votes to approve the report in its current form on 9 July, can't force the Commission to follow its recommendations.

Update 10 July 2015

The European Parliament has now voted on its recommendations for copyright law. It decisively rejected the idea of restricting 'freedom of panorama', but neither did it push for all EU countries to adopt the same broad exception that applies in the UK, as some MEPs proposed.

The final report sent to the European Commission no longer contains any reference to freedom of panorama either way.