EU immigration and pressure on the NHS

EU immigration contributes to financial pressure on the NHS, but its annual impact is small compared to other factors. Whether EU immigrants pay enough into the public finances overall to cover their costs is difficult to say, and researchers give different answers. However, it does appear that they make more of a net contribution than other groups. The UK doesn’t claim back as much as it could of the cost of treating Europeans who come here for a shorter period as visitors or to live as pensioners, which is mostly down to the NHS not asking for money it is due.

EU citizens moving into and through the UK change both sides of the NHS’s financial equation. They affect the number of people who must be treated—but by paying taxes or transferring money from their home countries under schemes such as EHIC, they also affect how much money the health service has to spend. The question is: do they cover their costs?

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Are EU immigrants driving current pressure on the NHS?

The trust deficit and the wider pressures the NHS faces are driven by an unrelenting increase each year in the cost of treating patients coming forward. Is EU migration an important contributing factor in this?

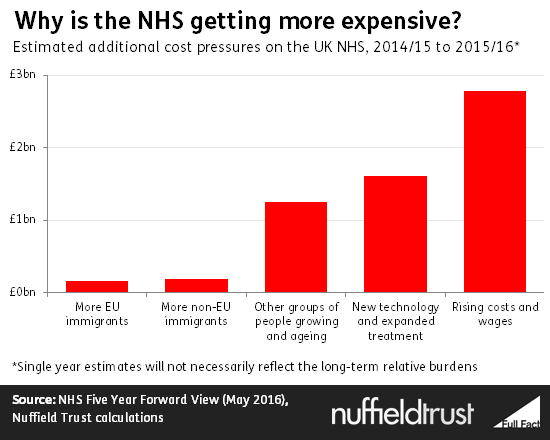

We estimate that in 2014, migration from the EU added £160 million in additional costs for the NHS across the UK.

That figure has been arrived at by using NHS England estimates of cost to the health service for people in different age groups. We can add these costs for migrants who arrive, and subtract them for those who leave, to estimate the total cost of migration from the rest of the European Union. It assumes that they use health services at the same rate as people of the same age already in Britain—which some studies support, although there is also evidence that EU immigrants may be healthier.

£160 million is a significant figure. However, it is small compared to the additional costs caused by other pressures on the health service.

The same technique suggests that £1.4 billion in additional costs were caused by other changes in the number and age of people in the UK. The biggest contributor to this was the growing and aging native population, as well as immigration from outside the EU.

Applying estimates from the NHS in England to all four countries of the UK, we can also look at pressure unrelated to population change. Last year saw around £1.6 billion in extra costs from new technologies and the financial implications of trying to improve standards of care, and £2.8 billion from inflation and rising wages.

Is immigration from the European Union a net burden on the NHS?

In the longer term, immigrants are taxpayers as well as patients—they affect how much money is available for the NHS, as well as how much it is asked to spend. Are EU immigrants taking more out of the system than they put in, at the expense of British-born users of the NHS? Or are they making a net contribution which benefits those already here and allows us to fund the NHS more generously than if they had not come to the UK?

Almost all NHS funding comes from the government’s central budget so we need to look at the public finances as a whole to see the impact of immigration on the NHS.

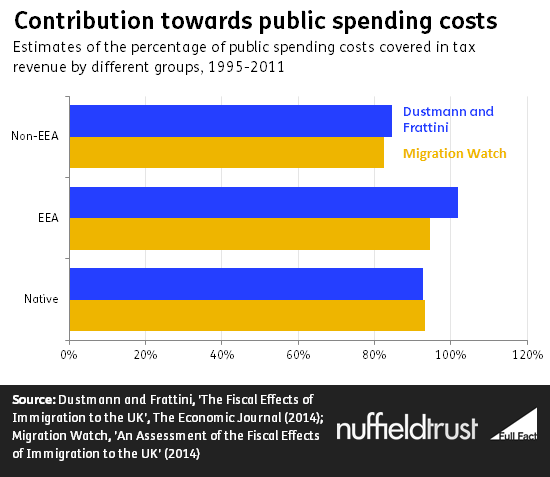

This is an inexact science, and different researchers come to different results.

For example, two studies have been carried out on immigrants living in the UK between 1995 and 2011—one by academics at UCL, and another by the campaign group Migration Watch.

Both studies agree that immigrants from the European Economic Area (Norway, Iceland and Liechtenstein plus all EU countries) made a more positive contribution than UK natives—and a far more positive contribution than immigrants from outside the EEA. However, over this period the UK as a whole ran a budget deficit, which means that the population as a whole received more in public spending than it paid in tax.

In this context the studies disagree on whether EEA migrants contributed enough more to actually be net contributors overall.

Under the UCL figures their net effect was to add £4.4 billion to public coffers, whereas Migration Watch find that the overall impact was a loss of £13.6 billion.

As the studies cover sixteen years in which several trillion pounds were gathered and spent by the British state, these are relatively small differences, suggesting that EEA migrant tax revenues have been at least in the same ballpark as the money spent on them.

Both studies agree that recent immigrants (those arriving since 2000) have made a more positive contribution to the public finances than those covered by their longer studies—as we might expect given that this does not include older groups who use more welfare and are more likely to be retired.

How could the pressure from EU immigration change if the UK remains part of the EU?

There has been much debate around future immigration if the UK remains in the EU, and what it might mean for the NHS. But the existence of freedom of movement makes it very difficult to predict movements in the longer term. Immigration in recent years has been driven by the UK’s economic strength relative to southern and eastern European countries—and fluctuations in relative economic performance, driven by many complex factors, will determine its future levels.

Vote Leave campaigners have emphasised the possibility of more countries joining the European Union and have argued that this could place a particular burden on the NHS. This involves even more completely unknown factors. The country talked about most, Turkey, is a candidate to join the EU. But it’s unlikely to join any time soon and there are currently considerable barriers to it joining.

Again, whatever happens, the critical consideration in terms of pressure on the NHS would be not just the numbers who arrive, but whether they cover the costs they incur.

Are we getting a bad deal on the health care costs of visitors and pensioners moving to and from the UK for short periods?

In March this year the Labour MP John Mann published the results of a Parliamentary Question asking how much the UK had received from EEA countries for treating their citizens on the NHS, and how much money those countries had received for treating British citizens.

The UK paid £674 million to other countries, while receiving just £49 million in return.

There are several arrangements under which care in the EEA is charged to the country whose citizen is treated abroad in this way. The most notable are the European Health Insurance Card (EHIC), which covers health care for short term visitors, and the S1 document which covers the health care costs of expatriate pensioners.

The size of the difference between the amount the UK pays out and the amount it receives is partly because foreign citizens in Britain run up less than half as many costs which might be covered under these schemes as British citizens abroad. However, government studies suggest that the NHS is also simply failing to charge when it is supposed to—recouping only a fraction of what should be around £340m from other countries.

This means the UK effectively gets a poor deal from these schemes. But the discrepancy is not closely linked to the fact of EU membership. It is largely down to the NHS failing to recoup costs as other EU countries do. Government papers suggest that this is because NHS trusts find it easier not to record that they are owed money from abroad, thereby getting full payment from the standard system without the extra admin involved in tracking foreign visitors.

Although the scheme is currently implemented through the EU for the UK, the EHIC card initiative also applies to non-EU members of the EEA as well. Britain could remain one of these even if it left the EU.

If the UK did leave both the EU and the EEA—which would be required to limit European immigration—then it would be released from these schemes. European immigrants would then fall under the charging system for general immigrants, which the government has also acknowledged has some issues with the NHS not demanding payment when it should. British tourists and pensioners abroad would have to cover health care costs from their own pockets or from travel insurance, without EHIC cards or S1 documents.

A replacement deal could be negotiated: the UK also has arrangements to cover the costs of people visiting countries such as Australia. However, this might take time in which visitors had to go without cover, and might not apply to all European countries.