Explaining the EU deal: is it legally binding?

The Prime Minister’s renegotiation deal on the UK’s European Union membership is a package of changes to EU rules. It was agreed by European leaders on 19 February 2016. In this series of articles, some of the country’s leading experts in EU law explain the deal and what it changes.

This is a shorter version of a blog post on the EU Law Analysis blog.

The stated objective of Prime Minister was to get an agreement on the renegotiation of UK membership of the EU that is “legally binding and irreversible”. Did Mr Cameron achieve his aim?

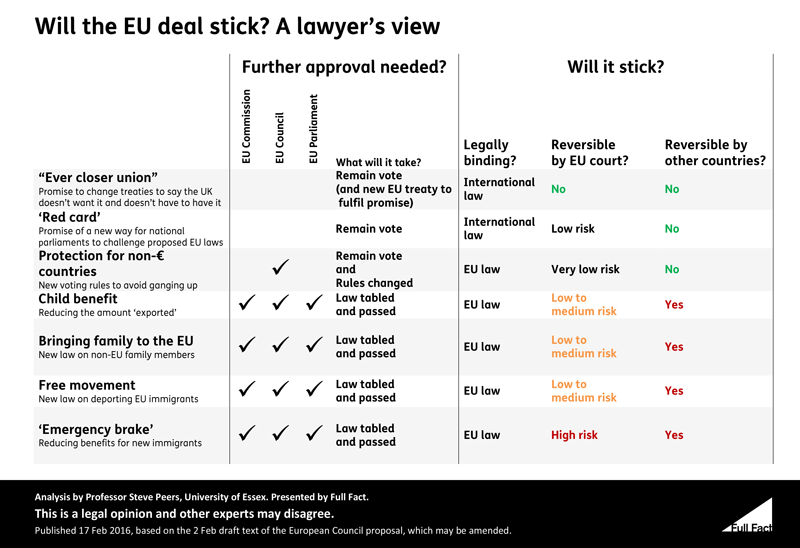

The answer is complicated, because there are several different parts of the deal, taking different legal forms. We’ve provided a quick summary.

For each part, the legal status depends on several different factors: when it would be passed; who would have to approve it; whether the EU courts have power to overturn it, and whether they are likely to do so; and whether it could be repealed or amended in future.

Main part of the deal is international law, not EU law

The EU deal takes the form of six legal texts. It also implies three new EU laws, all dealing with the free movement of EU citizens (the emergency brake on benefits, EU citizens’ non-EU family members and export of child benefit), which are referred to in these texts.

The government is also likely to propose domestic laws linked to the renegotiation deal, for instance on sovereignty and the EU Charter of Fundamental Rights.

The main legal text is called the Decision of the Heads of State or Government.

This includes the promises to exempt the UK from “ever closer union” by changing EU treaties and to give national parliaments a ‘red card’ to challenge proposed EU laws.

It’s not EU law as such; it’s international law. It’s not an act of the European Council, which is the EU institution consisting of heads of state or government, but rather of the heads of state and government acting in their own name.

That distinction might sound pedantic, but it has legal consequences.

The government intends to register the Decision as an international treaty.

Making a deal between member countries using an international treaty isn’t new to the EU. It was done in 1992, to encourage Danes to ratify the Maastricht Treaty, and in 2009, to encourage Irish people to ratify the Lisbon Treaty.

When European leaders declare it “legally binding”, they mean it’s legally binding under international law, not EU law.

Under international law, it's “irreversible” in the sense that the UK government would have to consent before it could be amended or repealed.

The Decision will not as such change EU law, although other elements of the overall deal would: the planned legislation on free movement issues, and the promised decision on eurozone issues.

Indeed, the Decision couldn’t change EU law without following the formal procedures to do so. It explicitly recognises that it can’t have that effect.

This part of the deal can’t be directly enforced in the EU court, but can’t be attacked there either

The Decision can include legal obligations for EU members as a matter of international law, as long as this doesn’t conflict with EU law.

In the event of any conflict, the primacy of EU law means that it takes precedence over the Decision.

The distinction between the Decision and EU law does mean that there is a gap in the Decision’s enforceability.

A dispute about enforcing it can be brought back before the European Council. But there is nothing on bringing a dispute before the EU court, which could then impose fines.

So despite the binding nature of the Decision, there isn't a clear mechanism for making it stick.

On the other hand, because the Decision isn’t part of EU law, another country couldn’t directly challenge it before the EU court either.

Other parts of the deal changing EU law itself could be legally challenged or blocked by politicians

There are plans that would change EU law.

The plans to change the treaties themselves (on “ever closer union” and the eurozone) essentially require the consent of all EU countries and ratification by all national parliaments (with possible challenges in national courts).

The EU's administration. It proposes new laws as well as overseeing existing ones.

The change to voting rules on certain eurozone laws can be done by governments through the Council. It doesn’t need to be proposed by the European Commission, or agreed by the European Parliament.

The deal also says that a law will be passed on the ‘emergency brake’ on in-work benefits for EU migrant workers. There will also be a law relating to the non-EU family members of EU citizens who move between countries. And there will be a law about the 'export' of child benefit.

Is there any guarantee that these laws will be officially proposed; be passed; not be struck down by the EU court; and not revoked?

Some of the necessary political approval is secured in advance

It’s up to the European Commission, or administration, to make proposals to start the process of passing these laws. The deal doesn’t force the Commission to act. But it includes two declarations by the Commission, announcing its intention to make these proposals.

For those proposals to be passed, they must be approved by the EU’s Council (by a qualified majority) and the European Parliament (by a majority of the vote, under most variants of the EU legislative process).

Again, the deal can’t bind the Council or the parliament. But the Council is made up of member countries’ ministers. In the deal, those countries commit themselves to supporting two of these three proposals (on child benefit and the emergency brake).

The Commission says that it will propose them after a ‘Remain’ vote.

However, the EU’s parliament and court aren’t bound by the deal. It remains to be seen whether the parliament will object to some or all of the planned laws. This might become clearer closer to the referendum date.

Some of the laws proposed in the deal could be legally vulnerable

The position of the court would only be clear if a legal challenge reached it. That would be some years away.

I made an initial assessment of the planned changes in a separate blog post on free movement issues. The most vulnerable seems to be the emergency brake.

Other experts may disagree.

The laws could be repealed, although that’s highly unlikely

Leaving aside the question of court challenges, could the legislation be revoked or amended, after it was passed?

In principle, that is possible. The UK could not veto it.

But the Commission’s commitment to make these proposals and governments’ commitment to support at least two of them suggest this is not going to happen, because the law could not be overturned without a proposal from the Commission and support from member countries' ministers.

Overview: is the draft deal legally secure?

It follows from the above that the renegotiation deal is binding. But there are two significant caveats to that.

Parts of the deal, concerning the details of the changes to free movement law and Treaty amendments, still have to be implemented separately.

And there are limits to the enforceability of the deal.

Update 24 February 2016

We revised the article to take into account the final version of the EU deal published on 19 February, rather than the draft of 2 February as in the original.