Brexit plans: five key arguments factchecked

With the Conservative leadership race now down to the final two, we’re hearing a lot of claims about what both remaining candidates would do in order to secure a Brexit deal by 31 October.

Jeremy Hunt, for example, has emphasised that he believes getting a new Brexit deal from the EU is “about the personality of our Prime Minister… someone that the other side will talk to who's going to be very tough”.

Meanwhile Boris Johnson has laid out a plan to “disaggregate the elements of the otherwise defunct withdrawal agreement”. It includes a plan to “reserve” the payment of the £39 billion divorce bill, and to only “solve the problems of free movement of goods” across the Irish border after Brexit, during the implementation period. Failing that, his “plan B” is to get a “standstill” agreement using something known as GATT 24.

Obviously, you can’t factcheck the future - it’s almost impossible to say definitively whether any particular negotiating strategy would or would not work. But, to date, many of the arguments we’ve heard have alluded to or repeated claims about the Brexit negotiation process which are either misleading, or highly unlikely when you take into account current political realities.

Many of the elements of the Brexit plans being discussed in the leadership debate are things we’ve written about before - often repeatedly. Here, we’ll round up five of the most commonly repeated points about how to get a Brexit deal over the line that we’ve covered before.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Taking the Irish backstop out of the withdrawal agreement

This is a popular approach among many MPs, but it seems very unlikely to result in workable deal, as the EU has remained adamant that any deal must include such a backstop.

To save time, we won’t explain here what the Irish backstop is—but you can read our explanation of it here (shorter) or here (longer).

The Irish backstop is part of the withdrawal agreement which the UK and EU first negotiated in November 2018. That agreement has so far been rejected three times by the UK parliament.

A key reason why some MPs say they have refused to vote for the withdrawal agreement is because of the Irish backstop, so a withdrawal agreement without a backstop is more likely to be passed by MPs.

But the issue is that senior EU figures such as Donald Tusk, Michel Barnier and Jean-Claude Juncker have repeatedly said that they will not sign up to any withdrawal agreement that doesn’t include a guarantee on the Irish border, and that the current withdrawal agreement (including the backstop) is not up for renegotiation. This position has recently been reiterated by the Irish Taoiseach (Prime Minister), Leo Varadkar.

Using tech solutions to get around the Irish backstop

Another repeated line is about the possibility of technological solutions or alternative arrangements to replace the backstop (for example an IT system linking customs declarations and vehicle registration numbers).

The EU is not opposed to this in principle, but the problem is that a technological solution— which would keep the border open as it is today even if the UK and EU had different customs regimes— doesn’t currently exist.

No clear plan for a technological solution has been outlined, and Ireland does not consider this a realistic solution before the Brexit date of 31 October. In this context, the EU insists that the Irish backstop is the only realistic way to guarantee the Irish border stays open, and thus insists on it staying in the withdrawal agreement.

Abandoning the withdrawal agreement, and settling the Irish border during the implementation period instead

Another common argument is that you don’t actually need to pass a withdrawal agreement to resolve the stickier points of Brexit, and that this could be done during the “implementation period” instead.

This is incorrect, and we’ve corrected politicians for making false claims like this again and again and again and again.

The “implementation” or “transition” period is set out in the withdrawal agreement, and it is designed to smooth the process of the UK’s exit. It would kick in after Brexit, and keep the UK aligned to the EU’s single market and customs union while we negotiate a future trade agreement with the EU.

So for the implementation period to kick in, you need to pass a withdrawal agreement. And as we explained above, the EU have said they won’t sign up to a withdrawal agreement unless it includes the Irish backstop, or another mechanism to guarantee that the Irish border stays open after Brexit.

No withdrawal agreement means no implementation period.

Using “GATT 24”

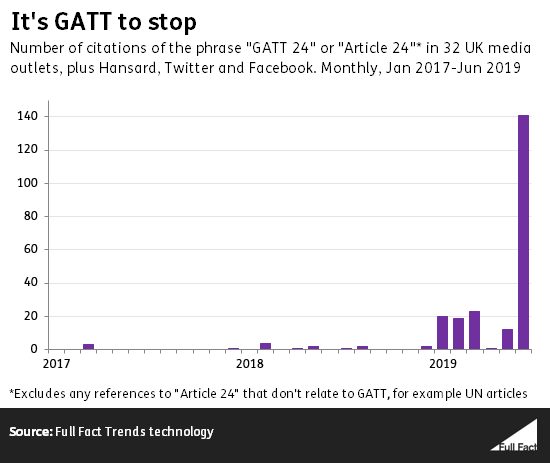

A further commonly-repeated suggestion is that we don’t need a withdrawal agreement or an implementation period because of something called “GATT 24” or “Article 24”. In the last week or so, GATT 24 has been invoked by, among others, Boris Johnson, Daniel Kawczynski, Priti Patel and Iain Duncan Smith.

The term “GATT 24” was virtually never used in public discussion prior to 2019. Use of the term took off around the time that Theresa May began to try and get her withdrawal agreement through parliament. And after a lull in April and May, use of the term has rocketed in the past week, presumably driven by the Conservative leadership debate.

GATT 24 is a provision of the World Trade Organisation’s (WTO) trading arrangements. We would trade with the EU under WTO rules if we left the EU with no deal. The argument is that GATT 24 would allow us to leave the EU on 31 October without a deal and still continue trading with the EU as we do now, without any tariffs. GATT 24, the argument goes, allows two trading partners to maintain a “standstill” on their existing tariffs, while they finalise a new trade agreement.

But the problem is that this requires both the UK and EU to have reached an agreement on going into such a “standstill” period, and agree a plan and schedule for what the final trade deal would look like.

This scenario is very unlikely to come about. The EU says it would refuse to begin trade negotiations with the UK until the three main issues covered by the withdrawal agreement—the divorce bill, citizens’ rights, and the Ireland-UK border—were settled. These can’t be settled without the UK and EU signing up to some kind of deal first.

We’ve explained the problems with the GATT 24 argument twice before. Additionally, a range of government ministers and experts have explained the problems with GATT 24, including Bank of England governor Mark Carney, International Trade Secretary Liam Fox (a leading Brexit supporter), and trade experts such as Peter Ungphakorn.

Refusing to pay the £39 billion

A final argument is that we could refuse to pay the EU the “divorce bill” of £39 billion which was agreed between the UK government and the EU last year in order to get the EU to change its negotiating position. This is something Boris Johnson has recently claimed he would do, and in this video he refers to his intention to “reserve” the £39 billion payment.

It’s obviously not possible for us to predict exactly how EU negotiators will react. But it is worth clarifying that the divorce bill is not a fee which the UK is paying in exchange for a withdrawal agreement or free trade deal—rather it is the amount of money which the UK is considered to owe the EU in existing financial commitments (like to the EU’s budget), as agreed by both sides.

The EU has said that “the UK would be expected to continue to honour all commitments made during EU membership” in the event of a no deal scenario. Experts at the UK in a Changing Europe told us earlier this year that while it’s not clearly set out in international law that the UK would have to pay anything once it left the EU, the EU would be within its rights to take the case to the International Court of Justice on the grounds of the UK’s repeated commitments to pay.