Poverty, apprenticeships and house building: Prime Minister's Questions, factchecked

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Poverty

“...Why are there another half a million children living in poverty in Britain because of the policies of this government?”—Jeremy Corbyn

“Let me give him the figures.. 300,000 fewer children in relative poverty than in 2010.”—David Cameron

This isn’t the first time the Prime Minister and the Labour leader have clashed on what’s been happening to child poverty. The answer is all down to which measure of poverty you use.

After housing costs are taken into account, the number of children living in absolute poverty in the UK is up from 3.6 million in 2009/10 to 4.1 million in 2013/14. That's the 500,000 rise Mr Corbyn is talking about.

But the number of children in relative poverty (this time before housing costs) fell in the same period. It went from 2.6 million in 2009/10 to 2.3 million the following year, and has stayed there since. That's the fall of 300,000 the Prime Minister is referring to.

No one of the measures is clearly superior to the other, so it's not helpful for either side to highlight one of them in isolation. As the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) puts it, absolute and relative measures tell us different things, and "there is nothing to be gained from ignoring some of this information".

The IFS commented last year that the declining value of people’s pay had been a key factor in recent rises in absolute child poverty.

Apprenticeships

"Construction apprenticeships have fallen by 11% since 2010.”—Jeremy Corbyn

“I do have to pick up the right hon. Gentleman on his statistics, because we have seen a massive boost to apprentices ... under this government. Two million in the last Parliament, three million in this Parliament.”—David Cameron

18,300 people started apprenticeships in the construction, planning and built environment sector in England in 2014/15. As Mr Corbyn says that’s a fall of about 11% since 2009/10, when there were 20,600 apprentices.

The figures for 2009/10 might have included some duplicate learners—which is no longer the case in more recent sets of statistics. So the number of apprenticeships in this sector might have decreased by a bit less than 11% over this time.

Over two million apprenticeships overall were started in the last Parliament, a significant increase on previous years. The annual number of starts rose from less than 300,000 in the years up to 2009/10 to around 450,000-500,000 in 2010/11 onwards.

But the quality of these apprenticeships has been questioned. Some experts, such as Ofsted, have said that some of these apprentices are simply workers getting existing skills accredited.

The government has committed to delivering three million apprenticeships over the current Parliament.

House building

“House building under Labour fell by 45%. Since then it’s increased by two thirds. Over 700,000 new homes have been delivered since 2010.”—David Cameron

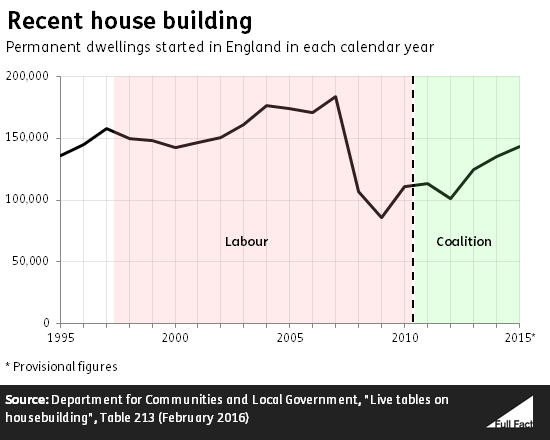

These numbers are correct. The decline in house building under Labour coincided with the recession.

While building has started on a generally increasing number of houses each year since 2009, it’s yet to return to pre-recession levels.

In the year Labour took office, construction began on 158,000 houses in England. In their last full year in power, when the UK was in recession, it was 86,000. That’s a fall of 46%.

Since then, the number of house building starts has increased by two-thirds, to 144,000 in 2015.

If instead you took homes completed in 1997 compared to 2009, the decline is only 16%, and similarly the recovery since is only 14%.

In terms of the number of homes “delivered”, over 700,000 new houses have been completed in England since the start of 2010. This will include houses completed before the Coalition government took office in May 2010, and some that started construction under Labour.

Stepping back and looking at the big picture, a similar number of homes were started last year as in 1996. House building is still low by historical standards.

Jobs for foreign workers

“Over two million jobs have been created since 2010 but nearly one million of those have gone to non-UK EU nationals.”—Anne Marie Morris MP

“Two thirds of the rise of employment over the last five years has been made up by jobs going to British people”—David Cameron

Roughly two thirds of the rise in employment over the last five years is accounted for by UK nationals and the rest by non-UK nationals, as the Prime Minister says.

Ms Morris’s claim is more problematic.

It’s correct that, of the change in employment since the start of 2010 (which is where the MP’s comparison starts), about 950,000 is accounted for by nationals from the rest of the EU.

But these aren’t “jobs created”—they’re how many more EU nationals are in work.

That’s because the figures—which do show over two million more people in work since 2010—will include jobs lost as well as jobs gained.

The same figures show non-EU employment fell over the same period. That doesn’t mean no-one from outside the EU found a job over the last five years, it just means that more moved out of work than moved into it.

“The EU's free movement of people is damaging UK nationals' employment prospects and has contributed to the 1.6 million British people remaining unemployed”—Anne Marie Morris MP

1.7 million people are unemployed in the UK, according to the latest estimates. That’s an unemployment rate of around 5%.

Immigration from other EU countries hasn’t been found to significantly affect unemployment. Research has suggested it impacts wages: low-paid workers lose and high-paid workers gain.

A study from 2012 did find that, although there was no overall impact, immigration from outside the EU was associated with reduced employment of UK-born workers.

The likelihood of non-EU immigration affecting British workers was greatest during economic downturns, according to the research.