Science: a girl thing, not yet a women thing — women in science in the UK

The European Commission's 'Science: It's a girl thing!' campaign launched at the end of last week.

A controversial video brought the campaign a good deal of attention. But is the campaign any better than the video was widely thought to be?

Dr Petra Boynton asked whether the real issue "is less about young women going into science, but staying in science careers... and also if it's a case of not studying science, or not doing it as career?"

The situation in the UK

The UKRC's 'Women and men in science, engineering and technology: the UK statistics guide 2010' is a thorough and well-sourced look at gender imbalances in sciences, engineering and technology (SET) in the UK.

While it was published in 2010 and often talks about data which might seem out of date, it can give us some rough indications on what we can expect from the gender balance today; data used by the Commission campaign is also often out of date by around the same amount of time.

Reading through the UKRC guide shows that one of the major problems here is the so-called 'leaky pipeline'.

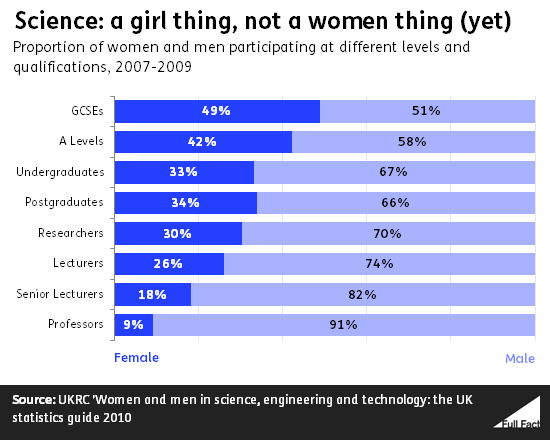

The proportion of women participating in science, technology, engineering and mathematics STEM qualifications and jobs decreases as we move up the ladder of secondary qualifications and vocational training, higher education, and careers in the workforce and academia.

At GCSE level, the numbers of boys and girls are very nearly equal, with 48.8 per cent of entries being from girls. That's not surprising because science is all but compulsory at GCSE level. By the time we reach the heights of the disciplines, however, fewer than one in ten Professors are female.

The graph uses figures for full-time employment but including part-timers does not alter the thrust. The only case in which women were more than half of part-time employees is among researchers, where they make 56.6 per cent. When it comes to part-time Professorships, only 8 per cent are held by women.

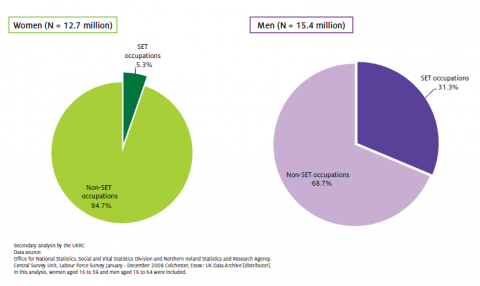

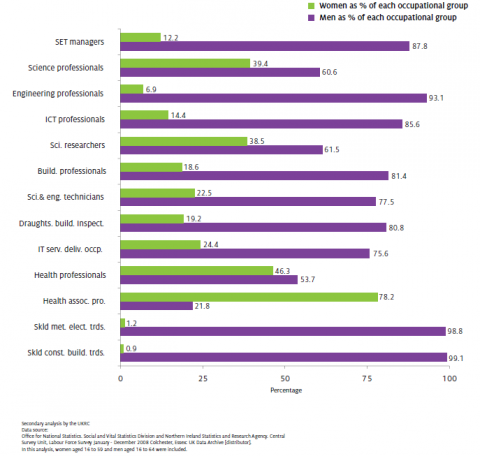

The SET workforce is explored by the UKRC in some detail. It's probably enough to point to the following charts, which show how few women are employed in SET areas, and how the women who work in these areas are distributed:

Overall, the UK has a clear gender imbalance in science. Dr Petra would appear to be correct in that the problem isn't so much that of girls and young women not wanting to get into SET: many sit STEM exams in secondary education and go on to study scientific areas during higher education. Fewer can be found in employment and academia.

On the other hand, even at A Level there is a marked tendency for boys to outnumber girls, and that tendency only increases as each year group gets further into their education.

Admittedly, these figures are only a snapshot. This is particularly relevant for the employment and academic figures; for example, it might well be the case that the 9.3 per cent of female professors is an accurate reflection of the number of women going into academia a good number of years ago, as professors occupy senior posts.

It is perfectly possible that the next few years will lead to the much higher numbers of women going through higher education and starting out their various careers having a noticeable effect on the statistics we've seen above.

However, as we'll show in part two of this article, the UK is hardly leading the European field supporting women in science, so we should not get unduly optimistic.