Are GPs to blame for more A&E admissions?

This article has now been updated with more information. (Please see below.)

"U-turn on GP hours as 4 MILLION swamp A&E."

The Daily Express, 25 April 2013

"Jeremy Hunt will say "disastrous" changes to GPs' working hours have led to an extra four million people attending hospitals annually."

The Daily Telegraph, 25 April 2013

Back in 2004 the Labour Government made GPs an offer: in exchange for £6,000 of their salary, they could reduce their working hours and would no longer need to be on-call during the evenings and at weekends. According to the Government, 90% of GPs opted to take the deal.

This means that if you now wake up on a Saturday morning running a high fever or your baby develops a red rash in the middle of the night, you might not be able to phone up your family doctor.

In these cases you would either call NHS 111 (the helpline that was previously known as NHS Direct) where you'd speak to someone who could advise you on what to do next, or alternatively you might make the trip to A&E.

Health Secretary Jeremy Hunt has argued that GPs, by working fewer hours, have created a crisis in Accident and Emergency departments. Last week he told charity Age UK:

"The decline in the quality of out of hours care follows the last government's disastrous changes to the GP contract, since when we now have 4 million more people using A&E a year compared to 2004."

Both the Daily Express and the Daily Telegraph picked up on the story, drawing a link between GPs working fewer hours and a rise in the number of A&E admissions. But is one the cause of the other?

Figures from the Department of Health (DH) offer evidence to support the Government's claim of an extra four million patients: in 2004/5 A&E departments in England treated 17.7 million people compared to 21.7 million in 2011/12.

Life of leisure?

So can we attribute the increase in A&E admissions to doctors working fewer hours?

Firstly, we don't necessarily know that only 10% of GPs are signed up to work out-of-hours (with the remaining 90% enjoying a 9-to-5 lifestyle). The British Medical Association has said that this statistic doesn't reflect the fact that many GP surgeries are members of 'cooperatives', which provide healthcare for their local communities during the evening and at weekends. We're still waiting for the British Medical Association (BMA) to provide us with more information on the number of cooperatives that do offer on-call services.

Also, it's worth noting that since 2004 the population of England has grown from 50 million to 53 million, while the average age of the UK population is older. Therefore the increase in A&E admissions may be partially due to our ageing population exerting greater pressure on the NHS. However, we can't easily say that this has been responsible for a specific number of extra admissions.

What's interesting is that if we take a slightly longer view we can see that rising A&E attendances aren't a new phenomenon.

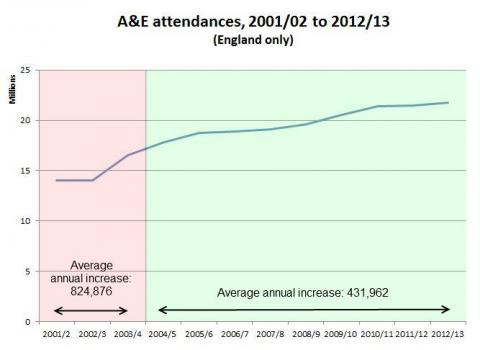

As the graph below shows, while the number of A&E visits has risen steadily since the introduction of the out-of-hours contracts in April 2004, there was also a recorded rise prior to this (at least between 2001/02 to 2003/04, which is the period covered by the data).

Source: DH data (2001-12, 2010-14)

In fact, the average annual rise prior to the introduction of the new contracts was almost twice as large as it has been since (if we look at the three years either size of the change, the difference is even more marked). The fact that we only have three years of data prior to 2004 means that we need to be a little bit cautious about the conclusions we draw on the strength of this information, but there certainly seems to be no sharp increase in the trend after April 2004. Tellingly, the sharpest jump was recorded before the Government offered GPs the new working hours contract.

The Government has commissioned a report into emergency care, the results of which are due next month. This might provide a closer look at any link between GP working hours and A&E visits.

As it stands, it's not clear that a shorter working day for GPs results in a greater workload for A&E - as the official statistics show, the biggest year-on-year rise in A&E admissions occurred before GPs were offered the chance to reduce their hours. We might therefore be dealing with a case of correlation rather than causation.

UPDATE (9 May 2013)

Today's Daily Telegraph quotes the head of the healthcare regulator as saying:

"Emergency admissions through Accident & Emergency (A&E) are out of control in large parts of the country … That is totally unsustainable."

David Prior, the chairman of the Care Quality Commission, was speaking at a conference organised by the Kings Fund, a healthcare think tank. As it happens, the Kings Fund has produced a useful graph that shows what's happened to A&E attendance over the last 25 years:

Source: The Kings Fund

The Kings Fund explains the leap in patient attendance between 2002/3 and 2003/4 by noting that it was at this time that we see an increase in the number of walk-in centres and minor injury units, which were designed to deal with some A&E patients. In other words, people with less serious injuries were diverted away from 'type 1' major A&E units into smaller 'type 2' and 'type 3' units. (A detailed description of each of these units is available from the NHS Commissioning Board.)

According to the Kings Fund, this suggests that a large portion of the 2003/04 increase is due to previously unrecorded attendances being logged but also new attendances at the type 2 and 3 units.

As we can see from the graph, it's attendances at type 2 and type 3 units that account for most of the increase 2003/04 onwards. Some of these people would have turned up at a major type 1 units if type 2 or 3 units didn't exist. However, what this data set does suggest is that patients with less severe injuries are mostly responsible for the rise in A&E admissions.

It may be that the creation of these type 2 and 3 units has stimulated the increase in the number of patients ('supply induced demand'), or that the units have been dealing with patients that previously wouldn't have sought treatment ('unmet demand'). Most likely, it's a combination of both.