Are you at greater risk of dying if you're admitted to the NHS at the weekend?

"Time to end the scandal of our 9 to 5 NHS...

...The risk of dying if a patient is admitted to A&E on a Saturday or a Sunday is 9.5% higher compared to the rest of the week, according to a recent study"

Daily Mail, May 07 2012

This week in the Daily Mail an anonymous author criticised the ability of the NHS to provide for patients outside office hours.

'Dr Nick Edwards' (not his real name) claims that the risk of death if a patient is admitted to A&E on a Saturday or a Sunday is 9.5 per cent higher compared to weekdays.

But does the NHS really shut up shop after 5pm?

Analysis

The 'recent study' cited by the author is the 2011 Hospital Guide, released by Dr Foster. Rather than being a super-human chap in a doctor's coat singlehandedly monitoring statistics across the entire NHS, 'Dr Foster' is in fact an organisation which describes itself as the "UK's leading provider of comparative information on health and social care services."

It is their report, released last year, from which the Mail's anonymous Doctor quotes directly. This research institution made the claim

"Being admitted to hospital at weekends is risky. Patients are less likely to get treated promptly and more likely to die. The chances of survival are better in hospitals that have more senior doctors on site. But some hospitals with A&E departments have very few senior doctors in hospital at weekends or overnight."

How it is measured

The report uses two main measures to arrive at this conclusion - 'Hospital Standardised Mortality Ratio' (HMSR) and 'Summary Hospital-level Mortality Indicator' (SHMI). Both are risk adjusted outcomes, comparing the number of actual deaths with the predicted number of deaths, which can be used to work out whether a mortality rate is higher than 'expected'.

HMSR compares the expected rate of death in a hospital with the actual rate of death by taking each diagnosis (heart attack, stroke etc) and calculating the average mortality rate across the country. This method allows for variables including age, the severity of the illness and geographical variations and produces the number of expected deaths per hospital.

The expected death rate is then compared with the actual death rate and each hospital is given a rating between 0 and 100 (perfectly matching = 100, 10 per cent higher than expected = 90, 20 per cent higher than expected = 80...)

SHMI assesses whether an individual Trust is within the expected mortality rate and is now the official NHS-wide mortality indicator for acute Trusts in England. It takes into account the risk profile of patients served by that Trust. It is a ratio of observed (actual) deaths to expected deaths, which is calculated from a risk-adjusted model with a patient case-mix including age, gender and diagnoses grouping.

Some critics have found the SHMI method to be the more reliable, as it gives each patient a probability of death which is then used to give a predicted value for the hospital. As a result, it is best to look at those data sets for which both methodologies find a 'High' risk.

Both measures find a 'High' risk in 19 of the 147 acute Trusts, however, this is a figure relating to total death risk, and is not broken down by weekend/weekday.

So why am I 9.5 per cent more likely never to make it out of a hospital if I arrive outside of normal office hours?

This, it would seem, is a good question. The 9.5 per cent figure does not appear in the report by Dr Foster.

After following the story back through a number of media outlets it seems likely that the the claim originates from The Telegraph who, in November, published the first article commenting upon Dr Foster's findings. In their article they wrote:

"Looking at emergency admissions, overall the death rate rises from 7.4 per cent on weekdays to 8.1 per cent at weekends, an increase of 9.5 per cent"

While it is uncertain where this particular claim originates, what is clear is that in utilising this figure, the Daily Mail's anonymous author may have conflated mortality rate and risk. The mortality rate (the number of deaths) does not take into account anticipated variations, and should not be confused with the mortality risk, which, as we have demonstrated above, is calculated through a different process.

Dr Foster do, however, outline the process by which they linked mortality rates to weekends:

"We picked two random Thursdays in March and April 2011 and asked each hospital trust how many doctors of each grade they had on site and on call. We then asked the same question for the following Sundays. We asked both about staff on site (in the hospital) and on-call (available to come into the hospital if needed).

"We have mapped these data for 130 (177 hospitals) of the 147 trusts and compared the figures to NHS bed data published by the NHS Information Centre for Health and Social Care and our analysis on weekend mortality."

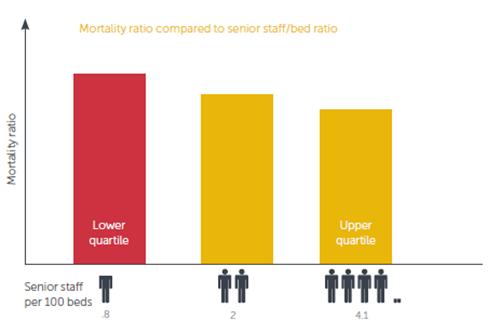

The conclusion Dr Foster reaches is that more senior staff per bed results in a lower HSMR (expected death count). A lower weekend HSMR is linked to more senior doctors as a percentage of total doctors.

Conclusion

Many sources have used the 9.5 per cent figure, but few have been clear about the evidence it is based on. It seems likely that the Daily Mail may have conflated 'risk' of mortality with the death rate, which as the measures show are not the same thing.

Those trusts with higher HSMR and SHMI than expected could be said to be riskier prospects, however a high mortality rate does not necessarily indicate a high risk trust because, for example, a larger number of your patients could be terminally or severely ill anyway.

The increased mortality at the weekend seems to be, in some part, simply down to the staffing levels at weekends compared to weekdays.