How medical staff found themselves at the centre of an information battle during the pandemic

Over the past months, as the coronavirus pandemic gripped the country, medical staff have found themselves – often unwillingly – at the centre of a parallel information crisis.

Throughout the pandemic, there have been numerous posts that attribute their claims to doctors, nurses, and medical professionals which have often turned out to be either false, needing vital context, or highly exaggerated. At Full Fact, we’ve seen someone create a fake NHS nurse account, fake information on death rates circled WhatsApp, and a doctor’s breathing tips go viral as they were taken out of context.

The virality of these posts has shown the appetite for “leaks” or insider information provided to doctors. The novel nature of coronavirus, and the understandable concern people have for their wellbeing, has left people grasping for any insight or explanations that they can get.

Added to this, the rise of medical influencers is yet another sign that the public is hungry for any insight that they can get right now.

However for medical staff, the novel coronavirus is a once in a lifetime challenge that they are undertaking, and learning about, often at the same rate as the public. Unlike viral posts suggest, they do not have quick and easy answers to the constantly evolving pandemic, and many feel unable to speak up about what they are experiencing out of fear of reprisal.

However for medical staff, the novel coronavirus is a once in a lifetime challenge that they are undertaking, and learning about, often at the same rate as the public. Unlike viral posts suggest, they do not have quick and easy answers to the constantly evolving pandemic, and many feel unable to speak up about what they are experiencing out of fear of reprisal.

It is true that there is real value in doctors’ stories right now. Anisha Gupta, a hospital dentist working in South London, has actively shared other medical staff’s experiences and key information like mask advice on her social media throughout the pandemic. She said her followers have found it extremely helpful.

"Several weeks ago, a good friend of mine who is a doctor had suspected COVID, and upon recovery made a really informative Insta-story of her personal experience with the disease and advice on how she managed isolation/quarantine and hygiene during her illness.

“I reposted the story to my own account as I consider my friend an excellent public speaker and communicator, and I had a non-medical friend message me to say how clear, informative and reassuring she found my friend’s Insta story, and how it alleviated a lot of her worry to hear a personal account from a health professional."

But while posts on social media can benefit non-medically trained users with accessible, advice, it’s far less simple for doctors to share the complicated and traumatic experiences they’re experiencing while facing a once in a lifetime pandemic.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

The anonymity problem

There has been a notable appetite for personal stories about doctors and patients during the pandemic, as the public tries to understand the complexities of a pandemic through human stories.

But while medically-trained and specialists in their skills, most frontline UK medical staff have never faced a pandemic before, let alone something like Covid-19 – a new disease about which the evidence is developing in real-time.

With posts from doctors going viral, it’d be easy to assume that medical professionals would be seizing the opportunity social media gives them.

But generally, doctors face a huge amount of uncertainty around how their behaviour and opinions will be met online.

There has also been considerable media space devoted to doctors who have faced a backlash from members of the public for posting fun videos during the crisis.

There has also been considerable media space devoted to doctors who have faced a backlash from members of the public for posting fun videos during the crisis.

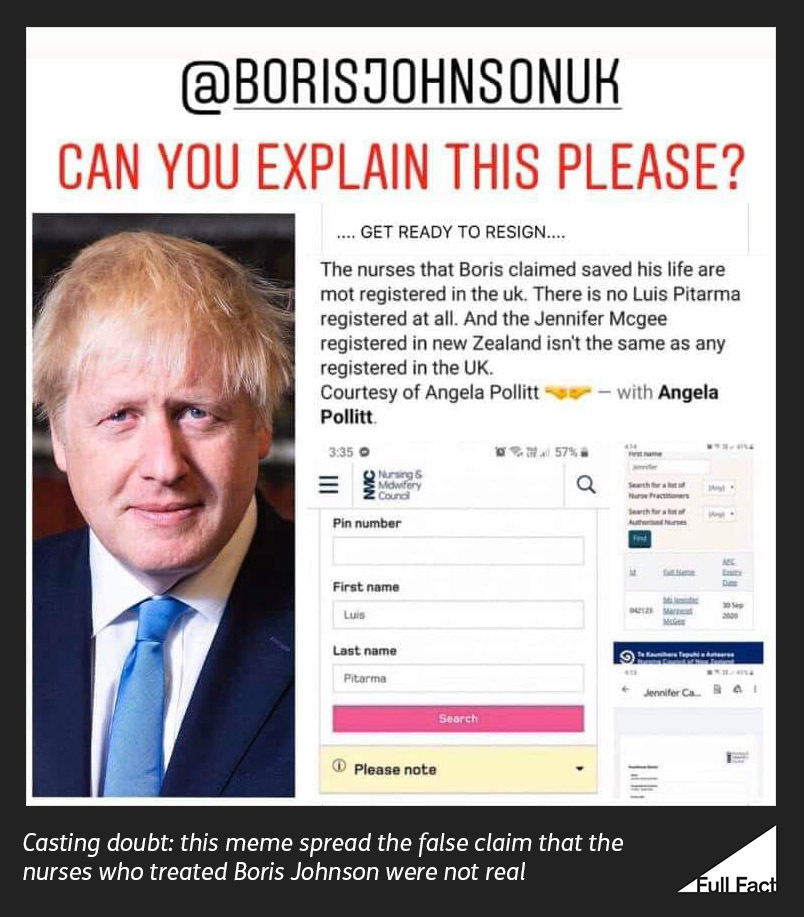

And two nurses and their social media accounts became the subject of conspiracy theories when they were named by Boris Johnson as two of the medical team that nursed him back to health when he was hospitalised with the disease.

Medical professionals’ behaviour on social media is largely guided by medical councils’ social media guidelines. The General Medical Council does not ban social media use and does say that social media use can have a benefit.

However, the guidelines require doctors to identify themselves when posting about being a medical professional on social media. Some have said this can put patients at risk.

One GP told Full Fact they worry that sharing too much publicly could breach patient confidentiality at such an emotionally-heightened time.

“Many of us feel that if we identify as doctors and share our name, then by default our hospital or community health care setting is known, and any stories we share could potentially be read by our patients or their relatives. When a patient comes to a health care professional they have every right to expect that the exchange of information and what happens during the course of their treatment is confidential.”

(For the record, as a rule, Full Fact does not use anonymous sources in its fact checks. For this feature article, we granted anonymity to some interviewees to enable them to specifically discuss the problems doctors have in speaking non-anonymously. We verified the identities and employment of each interviewee.)

Dr Julia Patterson from the Every Doctor campaigning organisation adds that even highly anonymised reports from individual hospitals can also put medical staff at risk - if there’s a limited number of a certain role at a hospital, for example, staff may feel that speaking to the press, even off record, could make their identity obvious. She says the group has been working to place stories from doctors into the media, most often anonymously.

And there have been some successes in directing media attention towards their highlighted issues using anonymised accounts. For example, numerous stories in the coverage of PPE shortages came about because of doctors either speaking anonymously or speaking through groups like Every Doctor.

But Patterson says that medical staff need to be able to speak up without fear of reprisal. ”We are sent a lot of examples of doctors being criticised, bullied and even threatened with losing their jobs if they speak up about the realities on the frontline of this national crisis.” This has been reported throughout the crisis by the British media.

The Hospital Consultants and Specialists Association told Full Fact, “Current employment law means that if they whistleblow directly to the press it is unlikely they will be protected from action by employers or have a right to compensation.” The NHS provides guidance on reporting issues internally, however, there have been noted reported examples of senior staff, trusts, and controlling NHS bodies disciplining whistleblowers.

The same boat

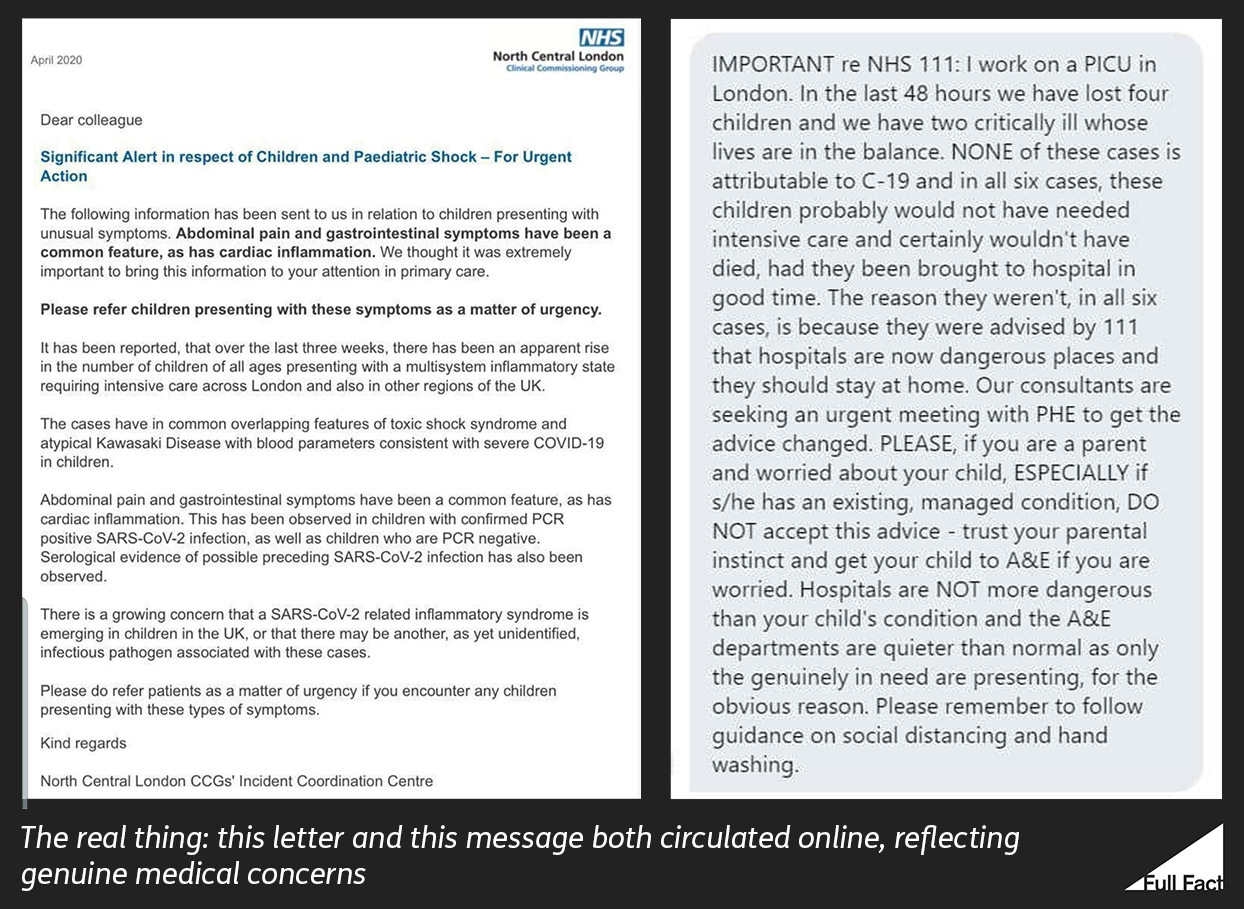

In late April a letter, sent to primary care staff detailing symptoms seen in some children with coronavirus, some without, became fodder for national headlines as people clung on to a small piece of information that confirmed a deep-seated fear. Medical professionals could be seen discussing the information, and what it meant, in real-time just as the wider public did.

Another post warning about children falling ill after not being taken to the hospital (in fear of these spaces being at over capacity) spread in a similar way - it originated as a news report in Health Services Journal, and slowly shaped into a text based-meme indistinguishable from the myriad of others circulating online.

The letters’ appearance on social media seems to speak to medics’ own confusion and desire for more information on the developing crisis - medical professionals were sharing these shreds of insight with each other as much as they are sharing them with their patients.

The letters’ appearance on social media seems to speak to medics’ own confusion and desire for more information on the developing crisis - medical professionals were sharing these shreds of insight with each other as much as they are sharing them with their patients.

One paediatrician told Full Fact that they believed the spread of the letter about inflammatory symptoms in children across social media was a move by doctors to ensure that colleagues were as well informed as possible. The letter was sent by a clinical group in London, but when shared to social media it quickly gained national and even global recognition.

“When something is new one cannot rely on case-control or other types of research. Much starts as anecdotes then reports of groups of patients with similar symptoms or who responded in a similar way to an intervention,” he said. “If they hadn’t shared doctors in the U.K. would each see 1 or 2 cases (as I have now done) and think nothing of it or just say that’s interesting.”

The doctor said while it is likely that awareness of the inflammatory symptoms would have eventually spread outside of London, speed is important in a pandemic, and it led to national data collection on these conditions by the British Paediatric Surveillance Unit (BPSU). (The set of inflammatory symptoms the letter identified in April continues to make headlines and be the subject of study.)

Across interviews conducted by Full Fact with doctors, health professionals and their representatives, a commonly expressed sentiment was that, despite a surge in interest in posts and quotes from doctors and hospital insiders, medical professionals were in a similar boat to the public, discovering changes and updates about the disease as many worked on the NHS frontlines.

Dr Natalie Ashburner of The Doctors’ Association UK says that many medical workers are currently using private groups to safely discuss the ever-changing information on coronavirus.

“The challenge in recent times has been the speed at which guidance and news is changing due to the novelty of the virus which has led to conflicting information circulating,” she said.

Dr Ashburner said their private Facebook group for doctors and medical students, previously known as “The Consulting Room”, saw a surge of membership when it was changed into a group for coronavirus discussion. The space now has over 15,000 members, who use it to discuss the rapidly changing situation safely among peers. Likewise campaign group Every Doctor also runs a popular Facebook group for doctors, The Political Mess, and told us that the group had been an important tool for doctors to sense check information they are seeing.

Dr Ashburner pointed to the confusion around whether ibuprofen should be taken by people with coronavirus as an example of one of the topics that had been discussed among members. The newness of the disease has meant that many doctors have been left searching for answers.

Under pressure

It’s undeniable that, with COVID-19, NHS staff are facing a deluge of novel challenges that most have never faced before. However, for staff members who already face hurdles in their day to day work, the pandemic has heightened these challenges.

Multiple sources told Full Fact that Covid-19 has deepened already-existing issues faced by the NHS’s minority staff. They said that BME medical staff, who make up around 40% of frontline NHS workers, have been facing unique pressure during the crisis, adding to the mounting difficulties faced in speaking out.

“There are definitely fears around safety/vulnerability (and ultimately increased risk of death) but the BME experiences we picked up were a lot more nuanced than that too,” said Dr Sahil Suleman.

Dr Suleman has been co-facilitating listening sessions for BME staff at South West London and St George’s hospital and said issues raised include anger at lack of clear guidance about the disease and response from management, risk assessment and testing, and fear over whether their work in healthcare was putting family members at risk.

Research from prior to the pandemic already showed that non-white medical staff face far higher rates of disciplinary referral - have behaviour reported to a medical regulator - than white co-workers. During the crisis, some minority staff members have also shared that they feel they are being put in more dangerous situations than white co-workers.

Ishita Rajan, a writer and creative, built a hub for BME people to find resources and share stories about the pandemic experience, says she’d also received similar stories via her hub of BME staff feeling unique pressure. She said many BME staff, particularly from less diverse areas, feel pressure to be representatives for their communities, leading to pressures that can affect how they communicate their experiences.

Generally, doctors’ groups and doctors themselves are keen to emphasise that they too are human and under enormous pressure during the pandemic.

“On top of these difficulties in speaking out, many doctors are under an unbelievable amount of pressure currently,” said Dr Patterson.

“We are contacted regularly by some media outlets who are very keen to pursue interviews with doctors at the end of long shifts, within their hospital or clinic settings. In many instances this simply isn't appropriate; to ask a person experiencing trauma to re-live their experiences on camera, in front of a national audience, can be re-traumatising and anxiety-provoking. It is incredibly important that NHS workers' stories are heard, but this is a sensitive, fraught area at the moment."

“Doctors are only human and share many of the same worries as the general population,” said Dr Ashburner. “They are also trying to cope with the restrictions in place, the loss of their usual coping strategies and the changing methods and demands of their work. They want to do their job to the best of their ability whilst keeping themselves and their families safe.”