Is the NHS in crisis?

"Why is the NHS in crisis?" is one of the most-googled questions on the NHS this election. But is our health service really in crisis? We joined up with the independent health experts Nuffield Trust to find out.

We can't go on like this. That was the stark message of a special House of Lords Committee on the future of the NHS:

"Our conclusion could not be clearer. Is the NHS and adult social care system sustainable? Yes, it is. Is it sustainable as it is today? No, it is not. Things need to change.”

They reported that "Many of our witnesses portrayed an NHS which is now at breaking point."

There are so many ways of measuring success in the NHS, across the different countries of the UK, that it will almost always be possible to find something to boast about and something to worry about. And the NHS probably does not have a single breaking point among all its different organisations and functions.

The Nuffield Trust, a leading health think tank, has looked across:

- Access to care – how many people are receiving care, how quickly?

- The money - NHS Finances

- The people - NHS staff

- The results - how patients are doing

The results show that the NHS does face significant problems in many different areas. It is succeeding in treating more patients than in the past, but this rise in need for care, and rising costs coupled with tight budgets, are translating into widespread pressures on the ability of staff and managers to keep up with past performance and the standards the service sets itself.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Access to care is getting more difficult

Waiting times are important to patients and are a key signal of how well access to healthcare is holding up. Two particularly significant measures of waiting times in the NHS are the time people wait to get a decision in A&E about where they go next, and the time people wait from a GP referral to planned treatment. While there are many other targets, these targets are notable for their breadth: they cross all conditions, and apply in one form or another across the UK.

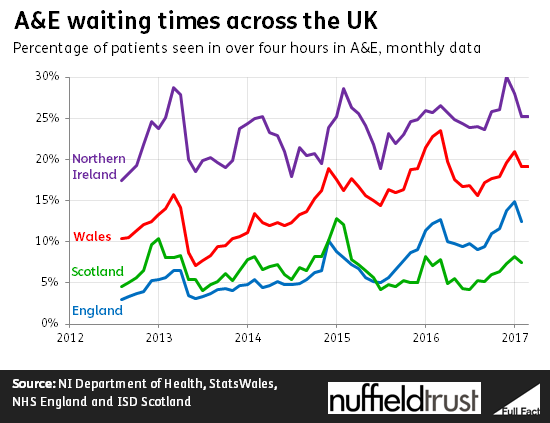

Wales, Scotland, Northern Ireland and England all have a goal that 95% of patients who come to A&E should have a decision taken about where they go next within four hours. The aim is to limit the time people wait in the emergency department before they are sent home, sent into the main hospital, or transferred to another service.

At one time or another over the last decade, this level of performance was achieved in Wales, Scotland and England. Now, all four countries are currently below it. As the chart below shows, there has been a gradual reduction in performance for the last five years. Even Scotland, which has kept performance fairly steady, has never managed to meet the target in winter when pressure tends to be higher.

For planned procedures like hip surgery the different health services have different targets, but again the signs of pressure are clear. Scotland and England are falling short of their commitments to treat nearly all patients within 18 weeks. Wales aims to treat patients within 26 weeks, but is not achieving this either.

These lengthening queues for treatment are happening despite the NHS treating more patients. In England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, the number of episodes of care provided in NHS hospitals has been rising. In England, for example, the number of episodes of care overseen by a hospital consultant has risen 11.4% between 2010/11 and 2015/16. It is just that the rise in the treatment provided is not keeping pace with the even faster rise in the number of people coming forward.

At the same time, England, Scotland and Wales have all started in different ways to look at reducing the provision of treatments deemed to be of less benefit to patients. That means that some people who would have got treatment on the NHS before might not in future.

Outcomes and effectiveness

Of course, access to care is not all that matters: the experience patients have, and the effectiveness of the care they do eventually get, are at least as important.

Here, there are better signs. Public satisfaction with services across the UK is holding up well, and at a relatively high level historically. The Nuffield Trust’s QualityWatch review of the NHS in England with the Health Foundation last year found signs that satisfaction from patients was also being sustained, although this is measured in many different ways across the UK.

Our report also found that care for hip fractures and stroke was still improving: more recent work has found that indicators of clinical standards in ambulance treatment are also improving or being maintained. In Scotland the NHS has set reduced mortality in hospital as an important measure of health service performance. This, too, is continuing to improve.

Services are financially overstretched

This decade health services have seen some of the lowest spending increases in their history. In England, real annual increases are only around 1% a year. Real terms spending has also been roughly flat per person since 2010 in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland.

This compares to an average increase of nearly 4% over the history of the NHS reflecting the fact that, as the OBR has found, an aging population, new technology and rising wealth all tend to increase health spending in a country.

Yet the amount of care being provided is still rising at over 3%, and prices in health care have usually risen more rapidly than in the wider economy. For example, the English regulator NHS Improvement believes the price of drugs will rise at more than 4% for most of the next five years, whereas prices across the board are projected by the Treasury to rise at less than 2%.

Efficiency drives are underway across the UK. However, there are signs that the NHS is not keeping up with the scale of the pressure. In England, NHS trusts are on track to overspend by more than a billion pounds this year. Similar overspending is visible in Scotland and Wales.

In a sense, these problems are not surprising. As the House of Lords Committee noted “The UK has historically spent less on health when compared with the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) averages. UK health spending per head is markedly lower than other countries such as France, Germany, Sweden and The Netherlands.” The Committee concluded that after 2020, health spending will need to start increasing more quickly again, at least in line with overall national income. That, they say, means “a shift in government priorities or increases in taxation.” The Nuffield Trust has looked at the financial implications and believes this would be sustainable.

Staff are in short supply

At the same time, the NHS is experiencing staffing shortages in key areas. These add to the pressure on services and have created an increased need for agency staffing in Scotland, England and Wales. In each country, regulators and independent bodies have expressed concern that agency staff are typically far more expensive, increasing financial pressure.

Nursing shortages leading to unfilled vacancies have become a serious issue across the UK. The Migration Advisory Committee found that as of 2015, 31,000 posts (or around 9%) were not filled in England alone. They agreed to formally list nursing as a Shortage Occupation for immigration purposes.

Vacancies are a serious issue in general practice as well, with one GP post vacant for every two practices in the limited number reporting data in England. Even as the number of appointments is estimated to be rising, latest figures show that the number of GPs fell in 2016 in both England and Scotland. There are similar problems with practice nurses. This is a particular concern given that all health services aim to provide more care outside hospital.

The Government is trying to get more medical graduates to become GP trainees, aiming to have 5,000 extra GPs by 2020. They also hope to increase the number of nursing training places, funding this by introducing tuition fees for courses that were previously publicly funded.

However, introducing fees for nursing seems to have reduced applications in the short term – although there are still more applications than places – and drives to persuade more people to train as GPs have fallen short for several years. In the meantime the UK is bringing in over 9,000 nurses from the EU each year, which may be harder after Brexit.

Long-standing concerns about the morale and engagement of staff may feed into this problem. Surveys of NHS workers for Scotland, Wales and England all show that on the whole staff disagree that there are enough staff for people to do their jobs properly, although there has been a slight improvement in recent years. Data for England shows that the number of staff giving work-life balance as a reason for their resignation has doubled between 2012/13 and 2015/16.