“Ten minutes’ exercise each week cuts risk of early death by a fifth”

The Times, 20 March 2019

“Exercising for just 10 minutes a WEEK can slash your chances of dying early by almost a FIFTH, study claims”

Daily Mail, 20 March 2019

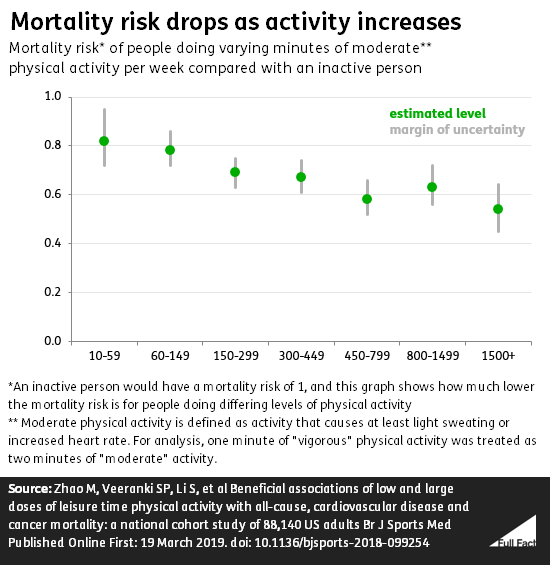

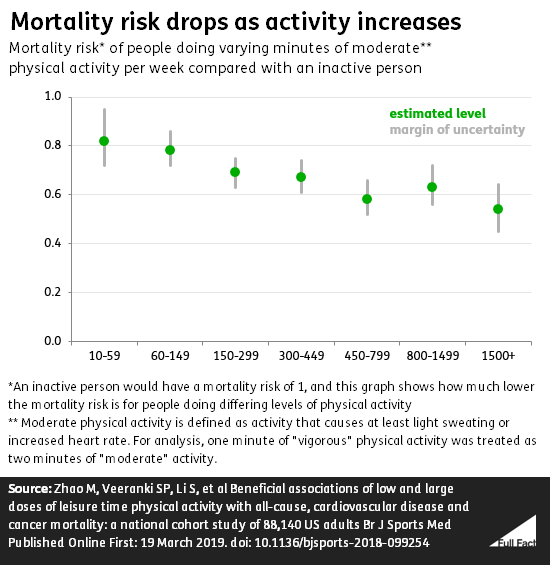

A new study has found that the risk of death was 18% lower among American adults aged 40-85 doing 10-59 minutes of moderate physical activity per week compared to inactive adults.

This wasn’t clearly reported by the Times and the Daily Mail who wrote that just 10 minutes (rather than 10-59 minutes) of moderate physical activity could reduce mortality risk by 18%.

Given that the risk reduction was seen amongst people who did moderate physical activity for 10-59 minutes, it’s likely that this risk reduction was lower among those who only did 10 minutes a week.

Moderate physical activity is defined as activity that causes at least “light sweating or a slight to moderate increase in breathing or heart rate.”

It’s also important to note that the study found that people doing 10-59 minutes of physical activity had an 18% lower mortality risk than those that did no activity—not that any additional 10-59 minute block of exercise reduced mortality risk by 18%.

In other words, the study doesn’t say that someone who is already active could cut their mortality risk by 18% by doing an additional 10-59 minutes of exercise per week.

The mortality risk did decrease among people that did more exercise, but the Times didn’t report this correctly.

It said: “Those who spent between 60 and 149 minutes on moderate exercise had a 28 per cent lower risk of dying from any cause.”

In fact the risk was reduced by 22%, not 28%, compared to an inactive person.

The study took data from an American national health survey to look at the impact of exercise on mortality. In trying to isolate the impact of exercise, the researchers “controlled” for other factors such as age, sex, smoking habits and body mass index. This means trying to limit the impact that these other factors have on the results so we can be more confident that changes are caused by exercise.

The study took data from an American national health survey to look at the impact of exercise on mortality. In trying to isolate the impact of exercise, the researchers “controlled” for other factors such as age, sex, smoking habits and body mass index. This means trying to limit the impact that these other factors have on the results so we can be more confident that changes are caused by exercise.

However, certain important factors were not controlled for, meaning the impact of exercise on mortality risk may be clouded by the impact of these other factors. The authors acknowledged this in their study, citing in particular the fact that dietary intakes and disabilities could not be controlled for.

We also note that access to medical care wasn’t one of the factors controlled for and as this varies considerably in the USA it could presumably have an impact on mortality risk.

That means that the reason why people doing more exercise had lower mortality risks, could have been, in part, because they had better healthcare, diets or fewer disabilities, rather than purely because they did more exercise.

Another important caveat the researchers note is that respondents only answer the survey once. So when the researchers followed-up to see whether the respondents were still alive, they had to class their physical activity based on what they were doing in the year they originally answered the survey.

That’s problematic because someone’s activity level could have changed considerably during that time. Someone who answered the survey in a year they weren’t exercising could have gone on to do lots of exercise in future years which would affect the mortality risk of the inactive group.

The study took data from an American national health survey to look at the impact of exercise on mortality. In trying to isolate the impact of exercise, the researchers “controlled” for other factors such as age, sex, smoking habits and body mass index. This means trying to limit the impact that these other factors have on the results so we can be more confident that changes are caused by exercise.

The study took data from an American national health survey to look at the impact of exercise on mortality. In trying to isolate the impact of exercise, the researchers “controlled” for other factors such as age, sex, smoking habits and body mass index. This means trying to limit the impact that these other factors have on the results so we can be more confident that changes are caused by exercise.