Is there a shortage of NHS hospital beds?

"It is completely wrong to suggest that the NHS cannot cope — the NHS only uses approximately 85 per cent of the beds it has available, and more and more patients are being treated out of hospital".

Dr Dan Poulter, Health Minister, 13 September 2012

According to several of yesterday's newspapers and TV news reports, we're facing a crisis in hospital care. We're told that compared to 25 years ago the number of beds in 'general and acute' wards has been slashed by a third.

At the same time we're informed that there's been a 37% increase in the number of people being admitted to hospital in an emergency. The majority of them are older people with more complex medical needs. For example, an Alzheimer's patient who's had a fall will need to be seen by more than one specialist.

So, are there too many patients and too few hospital beds?

The media's source is 'Hospitals on the Edge?', a new report by the Royal College of Physicians, which suggests the NHS hospital system is, as the RCP's President described it, 'on the brink of collapse'.

In response to the report, the health minister Dr Daniel Poulter issued a statement in which he said, "It is completely wrong to suggest that the NHS cannot cope — the NHS only uses approximately 85 per cent of the beds it has available, and more and more patients are being treated out of hospital".

But how do the Department of Health arrive at this 85 per cent figure? The NHS Information Centre collects data on the number of available beds and for the last quarter (up to 16 August 2012), the average bed occupancy was 85.8% for overnight stays and 86% for day visits.

However, for critical patients, the figures are higher (87.5% and 86.1% respectively). This means we drift further away from the minister's admittedly approximate statistic.

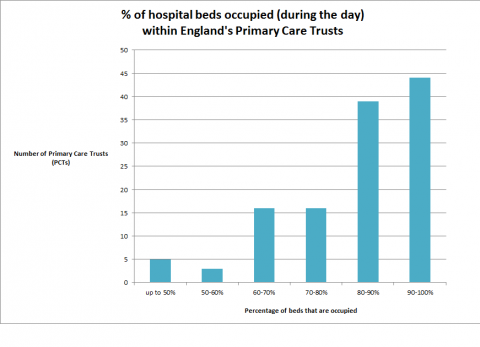

We can interrogate the numbers in more detail. The bar chart below shows that the number of PCTs with a day occupancy rate of between 90% and 100% is greater than any other decile. In fact, looking at the raw data, 24% of relevant PCTs were operating at full capacity during this period.

(Fewer PCTs submitted data for day occupancy rates because not all trusts provide day beds.)

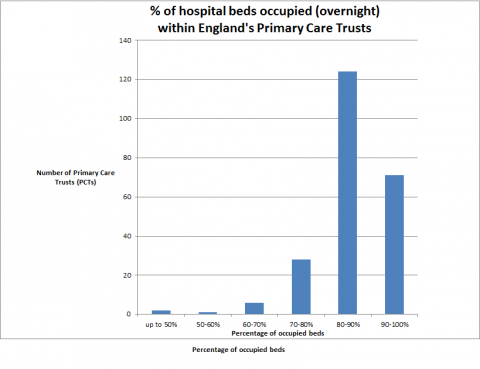

Similarly, for overnight stays, the large number of trusts with hospitals operating at 90-100% capacity accounts for the high average overall. Unlike for day occupancy, every trust has at least one spare bed.

If we talk about 85% mean occupancy, it's not the case that on an average hospital ward there are 15 beds in every 100 available at any one time. This is where it's helpful if we calculate the median, where the average has to be the middle number the data set, rather than the mean that's more easily affected by extremes in the data.

The median figure meanwhile is closer to 90% (more specifically, 88.5% for day occupancy and 90.7% overnight occupancy in acute care wards).

Does the government's statistic settle the debate?

The Department of Health's 85% statistic is not inaccurate. However, what it obscures is the considerable variation in bed occupancy across England's 232 Primary Care Trusts (PCTs) and across different wards. The government rebuts the RCP's claim about bed shortages by using data on bed occupancy from the last quarter.

And while the different figures aren't incompatible, the government's statistic doesn't actually disprove what the RCP is saying. We know that in some hospitals there are no spare beds. What the figures don't tell us is whether patients have been turned away from these wards because there isn't a bed for them.

It would, however, be reasonable to deduce that at some hospitals there is likely to be overloading of this kind. Meanwhile, at other hospitals bed provision is easily adequate.