Can we trust our immigration figures?

How many citizens from other EU countries are arriving, and staying, in the UK?

It sounds like a question we ought to have a simple answer to. Events last month made clear that we don’t.

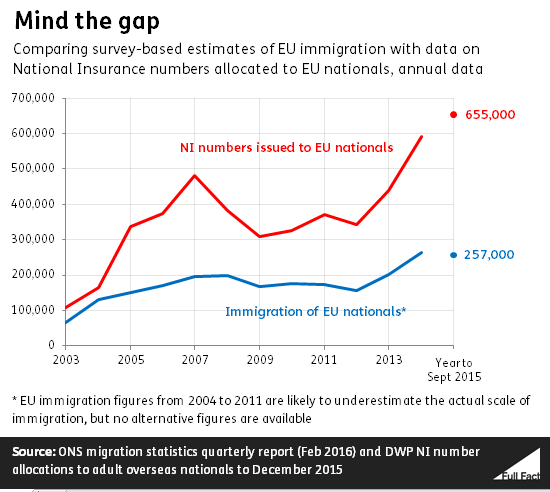

February’s routine immigration estimates suggested around 257,000 nationals from the rest of the EU migrated to the UK in the year to September 2015.

But another set of figures show that 655,000 National Insurance (NI) numbers had been issued to EU nationals over the same period. NI numbers are allocated to foreign nationals looking to work or claim benefits in the UK.

How can these figures be so different?

There are two main explanations: either our estimates of immigration are failing to count enough people, or there’s been a surge in people coming to work or claim benefits here for less than a year—the kind that NI number figures would pick up, but headline immigration figures would not.

We don’t yet know for sure which explanation is more likely.

Immigration estimates and NI numbers will never match exactly

Immigration estimates in the UK come mainly from a survey of passengers at airports and other ports across the country.

For people coming into the UK, the only way to distinguish immigrants from tourists and everyone else is by asking how long people intend to stay in the UK. If people intend to stay here for a year or more, they’re counted as an immigrant (a ‘long-term’ immigrant on the technical definition).

So the estimated 257,000 immigrants from the rest of the EU is based on a survey of a few thousand EU nationals who say they intend to stay here for at least a year. It’s an uncertain estimate: the ‘true’ figure could be up to 23,000 higher or lower than the estimate the vast majority of the time.

We also know that historical estimates of EU immigration are inaccurate. The survey of passengers was found to have missed a “substantial amount” of immigration from several eastern and central European countries in the 2000s.

NI numbers are more certain—the figures we have are a count of how many people are issued with one by the government.

But unlike the passenger survey, NI numbers don’t actually distinguish ‘immigrants’ from foreign nationals staying here for a shorter length of time.

There’s nothing to stop someone coming to the UK, getting an NI number, and leaving again before a year is up.

NI numbers also don’t tell us when people arrived in the UK. Someone could have arrived several years ago and only applied for an NI number recently. They’re a blunt instrument for measuring the inflow of immigrants to the UK.

So numbers from the two data sources shouldn’t really be the same—they’re not measuring the same thing. The Office for National Statistics said as much in a statement to us:

“It should be noted that the data on NI numbers and from the International Passenger Survey relate to different concepts. The figure for NI numbers issued to overseas nationals will include those issued to short-term migrants and to people who may have migrated some time ago but not previously entered the labour force. The IPS estimates are for long-term migrants—those staying for a year or more.”

In recent years, our estimates of immigration and figures for NI number allocations have been growing further apart. In particular, the amount of NI numbers being issued has grown considerably.

Short-term immigration could be the reason for there being far more NI numbers recorded than estimated immigrants

One explanation for the gap is simply that more people are coming here to work and/or claim benefits for less than a year.

These are people the passenger survey won’t count towards the main immigration statistics but will be included in the NI number figures.

The Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford told us:

“It is natural that National Insurance number allocations should be higher than the ONS measure of long-term EU immigration, because the immigration figures only include people who come to the UK for at least one year.

“The increased gap between NI number allocations and immigration figures could potentially be the result of a rise in short-term migration. It is also possible that the immigration figures have undercounted migration.

“Based on the data that is currently available, it is difficult to know.”

Large rises in short-term immigration have happened before. Following the entry of several new countries into the EU in 2004 (mainly from eastern and central Europe), the number of NI numbers issued increased hugely, outstripping the rise in estimated immigration at the time.

There were, however, large increases in the estimated number of ‘short-term immigrants’—people who claimed to be staying in the UK for over a month and less than a year.

So the same, potentially, could be happening now.

We don’t know because, for now, we only have short-term immigration figures up to 2013.

‘Short-term’ immigrants may leave again soon, or change their minds and stay

The immigration estimates do make an adjustment for 'visitor switchers'—people who change their minds and end up staying. But there could be more people doing this than the estimates suggest.

There’s some data to suggest that people may well change their minds.

Estimates of the adult population have tended to show larger increases in the population of people from the EU than are accounted for by the immigration estimates. Some of this could be due to EU citizens having children while here—but it could also be ‘unseen’ long-term immigration not picked up by the survey.

Immigration estimates may simply be undercounting people

The ONS pointed out to us that the differences between NI numbers and immigration figures after 2004 grew less over time. This suggests that short-term immigration was a factor in explaining the divergence.

But not everyone is convinced that’s the whole story for the latest gap.

The economist Jonathan Portes agrees that ‘hidden’ short-term migration will explain some of the disparity, but says it’s unlikely to account for the full scale of the difference.

As the Observatory says, the immigration estimates may systematically undercount the number of immigrants.

For now, though, there’s no evidence to suggest anything underhand is going on with how the figures are put together.

The answers are out there, potentially, but we’ll have to wait for them

The ONS told us it’ll be publishing a report in May this year to cover the issue in more depth, and we'll have short-term immigration figures up to the middle of 2014. That might give us a more thorough explanation for why there’s a growing difference.

More information about NI numbers is another potential source. One of the problems with the published figures is that they simply show how many have been issued—not whether they are actually being used.

Those are figures Mr Portes has been trying to obtain from the government, but so far the government hasn’t released them.

With access to these figures, we would be a step closer to understanding whether our estimates of immigration are fit for purpose.

Update (12 May 2016)

On 12 May the ONS published its analysis of the difference between the figures. We've summarised what they found.