EU immigration to the UK: what the National Insurance numbers reveal

Earlier this year, there was controversy over whether our immigration estimates have been missing large numbers of immigrants from the rest of the EU, with some outlets accusing officials of a “cover up”.

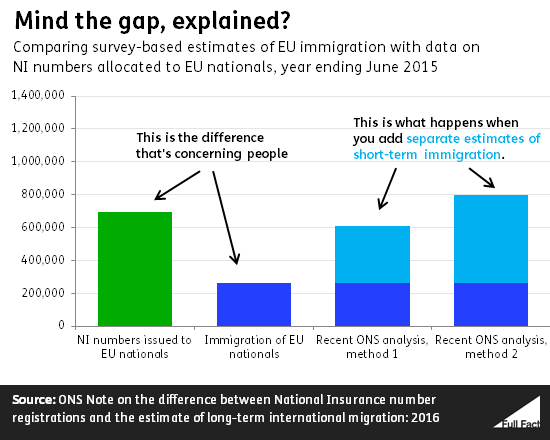

Routine immigration estimates in February suggested around 257,000 nationals from other EU countries migrated to the UK in the year to September 2015.

But another set of figures showed that 655,000 National Insurance (NI) numbers had been issued to EU nationals over the same period. NI numbers are allocated to foreign nationals looking to work or claim benefits in the UK.

In order to try and explain the gap, the ONS said it would publish an analysis this month. Today’s publication is the first installment of that.

What we learned today

The reason that the NI registrations imply so much more immigration than our official estimates show is largely because NI figures count more people in the first place, according to the ONS.

People are only counted in the headline ‘long-term’ immigration estimates if they intend to stay here for at least a year, following the UN definition. If they’re intending to stay for shorter periods, they’re counted separately as ‘short-term’ immigrants or just visitors.

NI numbers just count everyone who comes here and registers for one; people don’t need to stay for a least a year to do so.

The ONS says that, as a result of the work it’s done so far, the recent growth in these ‘short-term’ immigrants coming for less than a year “largely accounts” for the recent differences between the figures. And as a result:

“The International Passenger Survey continues to be the best source of information for measuring long-term international migration”

What we didn’t learn today

“Extra 1.5 million EU migrants came to Britain over last five years, official data shows”—Telegraph, 12 May 2016

"Boris Johnson blasts 'dishonest' ministers for misleading voters over 'extra 1.3 million migrants' in UK"—The Sun, 12 May 2016

No ‘extra’ immigration to the UK from the EU has been proven today, as headlines like these imply. We already knew about some of these extra 1.3 or 1.5 million people, as they were published separately as ‘short-term immigrants’ by the ONS. The rest were estimated in today’s analysis as recent figures aren’t yet available.

Short-term immigration—people who come for over a month and under a year—isn’t normally mentioned in headlines about immigration. Headline EU immigration to the UK is still measured by long-term immigration estimates and those figures haven’t changed.

This isn’t to say long-term immigration is the only measure we should be looking at. The government’s target for reducing long-term net migration continues to be a focus of the immigration debate, but the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford argued some time ago that focusing too much on this:

“creates a profound problem for public debate and immigration policy: focusing only on long-term net migration - the level of immigration minus emigration of people who intend to migrate for at least one year – risks failing to consider other vital data about migration in the UK – not least, how many migrants are actually here.”

Immigration estimates could still be too low

This is the first time the ONS has analysed its own migration figures alongside figures from both HM Revenue and Customs and the Department for Work and Pensions, to test its conclusions.

But this is very much chapter one of what could be an extended essay. The ONS intends to do further work “in due course”, although this is unlikely to be in advance of the EU referendum on June 23.

The economist Jonathan Portes, who first requested publication of more details about the National Insurance data, agrees that short-term immigration is the main reason for the difference, but he says it’s not the only explanation.

Today’s analysis “suggests some degree of undercounting of long-term migration from the rest of the EU”, according to Mr Portes.

For instance, an estimated 739,000 citizens of other EU countries immigrated to the UK in the four years to June 2014. Over the same period, HMRC found a million people from the European Economic Area registered for an NI number and were recorded as paying NI contributions or receiving certain benefits in 2013/14.

There are a number of reasons why these two figures should be different. Some people who immigrated during that period will have left. Not all will have registered for an NI number. On the flipside, of those who did get an NI number over that period, some will just be short-term anyway and not show up in the immigration figures.

Mr Portes says this difference still can't be reconciled without concluding that the immigration is an underestimate.

So today’s development by no means closes the debate over how accurate our immigration estimates are.

Correction (13 May 2016)

We've updated our description of the remaining unexplained 'gap' at the end of this piece to explain the reasoning clearly.