Brexit amendments in the House of Lords

The government was outvoted in the House of Lords twice this month over the draft law authorising the Prime Minister to trigger Brexit. Readers have asked us about the significance of these votes, in particular whether the government has to abide by what the Lords have voted for.

The short answer is no; the long answer is more interesting.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

The House of Lords can ask MPs to think again, but doesn’t normally try to overrule them

The Supreme Court ruled in January that the UK can’t leave the European Union without a law being passed to authorise it.

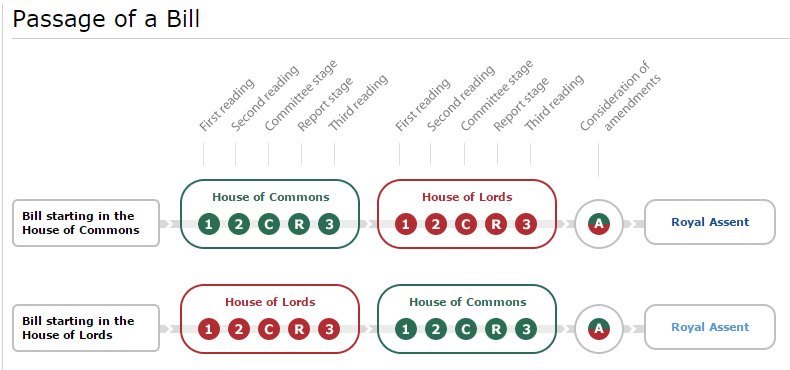

Laws are passed by parliament, which is made up of the House of Commons, House of Lords, and the Queen. As the Queen’s role is a formality, people often talk about parliament as being just the Commons and Lords.

MPs in the House of Commons duly approved the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill.

But in order to become law, a bill generally needs to pass in the House of Lords as well, before being rubber stamped by the Queen. The government doesn’t have a majority in the Lords—only around 250 of its 800 or so members are Conservatives.

The Lords can suggest changes to a bill passed by the Commons, and send them back to the Commons for consideration. Each House needs to vote for the same version of a bill for it to pass.

That primacy exists in legal form, such as in the Parliament Acts, which contain a procedure to override the Lords’ rejection of a bill.

In practice, the Parliament Acts have rarely been used, because of the political consensus that the Lords won’t block bills or repeatedly insist on amendments against the wishes of the House of Commons. Put another way, “in cases of conflict the Lords should ultimately yield to the Commons”.

What’s the point of the Lords if it always gives in to the Commons?

Its role is to get MPs to “think again”. Amendments give MPs the chance to take another look at the law they’re passing and decide whether it would be better in the form suggested by the Lords.

The Lords amended bills despite the objections of the government 50 times last year. Around one third of such defeats are overruled by the Commons, with the Lords taking the matter no further, according to the government’s guide to passing legislation.

Another third of defeats result in a compromise over the wording. The process of negotiating an agreed version between Commons and Lords is known as ‘ping pong’, as a bill can go back and forth between the two Houses multiple times.

A final one third of defeats “are conceded by the government”. That can be because the government doesn’t have the support of MPs to overrule the Lords, or because it decides that the Lords amendments are a good idea after all. So the Lords can get their way over laws from time to time.

And the government can make policy commitments in order to persuade the Lords not to vote against it, meaning that pressure in the upper house can have political impact even if draft laws go through unchanged.

What does this mean for the law triggering Article 50?

The House of Lords has considered the European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Bill and put in two amendments.

The first would require the government to “bring forward proposals” guaranteeing the rights of citizens from other EU countries who live in the UK. The second tries to stop the government from agreeing any Brexit deal with the EU, or from leaving with no deal, without the approval of parliament.

The House of Commons now has the opportunity to accept those amendments. It votes on them today (13 March). The government will be recommending that the Lords amendments be rejected.

If MPs reject the Lords’ amendments, the Lords will ultimately concede the point and pass the bill anyway. Labour’s leader in the House says “it is the House of Commons that will, as always and quite rightly, have the final say”.

Dr Hannah White, a parliamentary expert at the Institute for Government, expects there to be only “one round of ping pong” on this bill. In other words, one rejection of its amendments by MPs will be enough to make the Lords yield.

It’s only in the supremely unlikely event that enough Lords disagree with this standard approach to the primacy of the House of Commons that they’d vote against the bill. That would stop the government from triggering Article 50 by the end of March, but not block Brexit altogether, as the government could eventually force the law through using the Parliament Acts.

So, in the end, what matters is what happens in the House of Commons.