Shifting boundaries: what would reducing the number of MPs mean?

Last week, proposals were laid before parliament to reduce the number of MPs from 650 to 600 at the next election, and to redraw constituency boundaries to make them more evenly sized. Parliament is yet to approve the proposals, but we take a look at what impact they might have.

- Under the proposed changes, the number of seats in England would fall by 6%, compared to 28% in Wales, 10% in Scotland, and 6% in Northern Ireland.

- It’s estimated that, based on the new boundaries, the Conservatives would have won a majority of 16 at the 2017 general election.

- Boundary reviews are a regular occurrence, covered by national legislation, and are undertaken by independent Boundary Commissions in each UK region.

- Some MPs have expressed concern that reducing the number of seats without a parallel reduction in the number of ministers reduces the ability of parliament to scrutinise government.

- There’s contention over how representative the new constituency boundary lines are, as they’re based on data which misses out anyone who isn’t on the electoral register, or who joined it later than December 2015.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

What is being proposed?

In 2011, the Coalition government passed legislation that committed to reducing the number of parliamentary constituencies in the UK from 650 to 600. It also sought to make the size of parliamentary constituencies more even.

At the 2017 election, the largest constituency in England had almost 110,000 registered voters—the smallest had just over 53,000. The average number of registered voters in a constituency was higher in England (73,000) than in Scotland (67,000) and Northern Ireland (69,000), and Wales (57,000). This has led to arguments that the non-English regions are overrepresented.

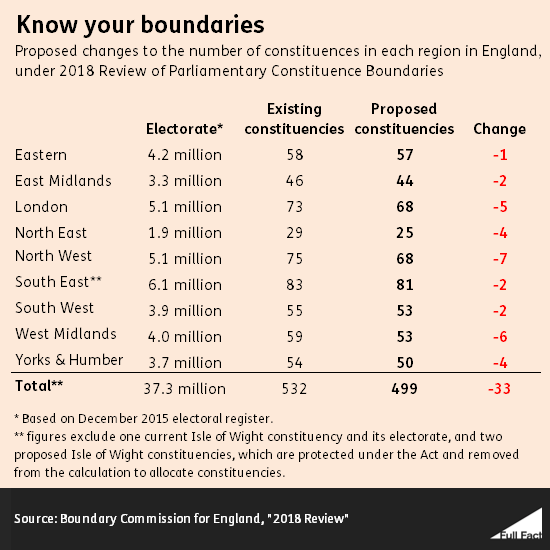

Proposals for the reduced number of constituencies have now been put forward. If approved, England will lose 32 of its 533 constituencies, Wales loses 11 of its 40, Scotland loses six of its 59, and Northern Ireland loses one of its 18.

Some constituency boundaries will also be redrawn to equalise their size. Under the 2011 legislation, constituencies must all be within 5% of the “electoral quota”—which, roughly speaking, is the total number of electors in each region divided by the number of proposed constituencies in that region (exceptions are made for a few island seats, which don’t have to be within the quota).

If approved the changes will affect some parts of the country more than others. In England, the number of constituencies will fall by seven in the North West, but only by one in the Eastern region.

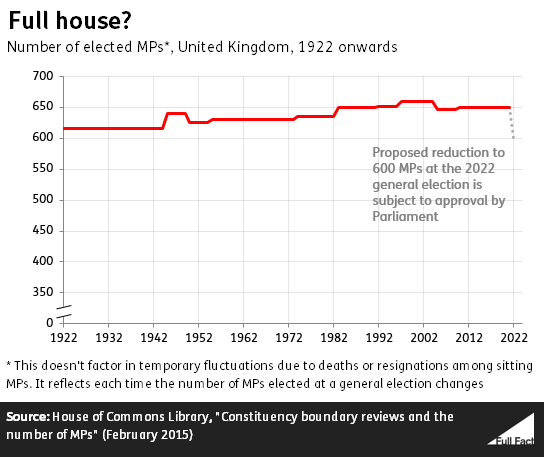

Constituency boundary reviews happen regularly

The redrawing of constituency boundaries has been a regular occurrence since the mid-twentieth century, though they also happened at irregular intervals before then. The number of constituencies has risen steadily from 615 in 1922 to a peak of 659 in 1997, and now stands at 650.

The proposed reduction in the number of constituencies is therefore a significant change by modern standards.

The latest change follows a 2007 parliamentary committee’s conclusion that the rules on boundary redistribution needed to be reformed, as they contained an inbuilt tendency to expand the number of seats at each review. The Labour government agreed but it wasn’t until 2011 that the Coalition government passed an Act committing to this reduction, as well as five-yearly reviews. A 2013 review by the Boundary Commissions was intended to enact these commitments, but was halted due to differences within government. Consequently, the Commissions were required to produce new proposals in 2018, and it is these new proposals which are the subject of this piece.

There is some debate as to whether the reduction of 50 seats is necessary. A 2013 parliamentary committee stated that it hadn’t seen a “compelling reason” for such a reduction. The committee agreed that the size of constituencies should be equalised, but recommended they be within 10% of the electoral quota, describing the proposed 5% as “strict”.

Expert reviews have also noted that the changes would lead to a high level of disruption to boundaries, and prioritise “arithmetic gains” over other considerations including continuity and geography.

Concerns have been raised about the data used to calculate the new boundaries

The proposed new boundaries are based on the electoral register of 2015. That year there were 44.7 million registered voters. By June 2017, there were an estimated 46.8 million people on the register

The Labour party says that this means “the voice of more than 2 million voters will be ignored”. This isn’t strictly true—the boundary changes won’t affect a person’s right to vote—but had the new boundaries been based on the June 2017 data they might look slightly different due to changes in the overall spread of voters across the country.

In 2016 the House of Commons Library looked at what the increase in the number of registered voters between 2015 and 2016 (an increase of 1.75 million) could potentially mean for the way constituencies are distributed. It found if the 2016 figures were used rather than the 2015 ones then, for example, London would see a reduction of three seats rather than five, whereas Scotland would see a reduction of eight seats rather than six.

It should be noted that boundary changes take time to map, so it may not always be possible to base them on the most up-to-date register.

Others have previously argued that boundaries should be based on the national census, not the electoral register, as it’s more representative of the total population that MPs serve, rather than just those registered to vote. Those living in urban areas are more likely not to be included on the electoral register.

How will this affect the political parties?

Media attention has largely focused on who stands to lose the most from the proposed boundary changes. These are highly speculative questions, but a few trends can be picked out.

It has been estimated that although all the parties would have had fewer MPs than were actually elected at the last election, based on the new boundaries the Conservative government would have had a majority of 16. Colin Rallings and Michael Thrasher, the academics at the University of Plymouth who did this analysis, told us it’s based on a method they’ve used before, based on extrapolating voting patterns in different wards from local elections data.

The media has also focused on the possibility of internal party disputes over which MP will represent a constituency in cases where two have merged. For instance, 49 of 73 Greater London seats are currently held by Labour MPs, including many of its most prominent MPs. The reduction in the number of seats in London by five could therefore mean that some sitting MPs have to look for new seats to contest.

The reforms could strengthen the hand of government over parliament

Some MPs and other parliamentary and independent campaign groups have expressed concern that the reduced number of MPs without also reducing the size of the government heightens the power of government over parliament.

Government ministers are bound by the principle of collective responsibility to support government policy in parliament. If the number of MPs is reduced but there is no reduction in the number of government ministers, this means a smaller percentage of parliament will be able to hold the government to account.