"DIY justice" or vital reform - what do we know about legal aid?

A "Vote for Justice" rally organised by a group of criminal law solicitors is taking place today, aiming to put legal aid on the election agenda.

We've taken a closer look at some of the important claims referred to when the BBC's Panorama covered legal aid last month—they come up a lot in the debate.

Legal aid is aimed at providing legal advice and representation to people who need it but may not be able to afford it. The government has been trying to reduce the cost of the scheme, but lawyers complain that access to the justice system is under threat.

"By 2010, the annual bill for legal aid in England and Wales had risen to £2.1 billion."

That's correct. By 2013/14, this was down to £1.7 billion.

The £2.1 billion spend on legal aid in 2009/10 was divided between legal advice and representation for people facing criminal charges (£1.2 billion) and legal aid for civil—non-criminal—disputes (£0.9 billion). Around two-thirds of the civil legal aid bill went on family law—the kind of cases addressed in Panorama.

But the cost of civil legal aid peaked in 2010—it had been lower in the decade up to then—and there was a further decline after 2010, according to data collected by the National Audit Office (NAO) and adjusted for inflation.

This second drop in the civil legal aid bill came before the implementation of the Legal Aid, Sentencing and Punishment of Offenders Act, known as LASPO, which limited the type of cases that are eligible for legal aid funding and who qualifies for it. It only came into force in April 2013.

So while some of the reduction in civil legal aid spending will be as a result of LASPO, spending was falling anyway.

The NAO thinks that the government's changes will save around £300 million a year. The saving comes from a 10% reduction in fees towards the end of 2011, and from 385,000 fewer cases of advice, legal representation and mediation being funded than might otherwise have been the case.

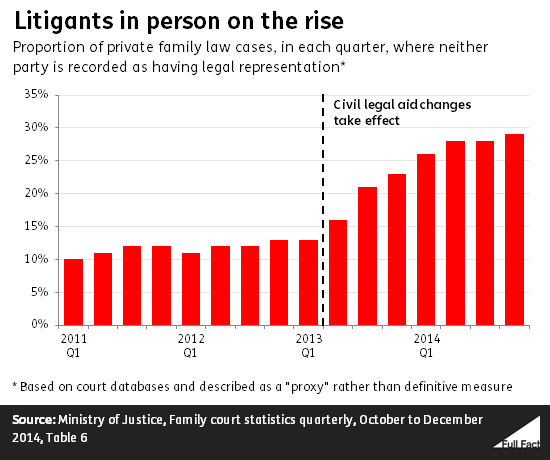

One result of this, in the family courts that are particularly affected, is a rise in "litigants in person", or LIPs—people in court without a lawyer.

The proportion of private family law cases—mainly disputes over finances or arrangements for children after divorce—in which both sides are recorded as having a lawyer has halved over the past two years.

Most people without a lawyer would have one, if they could afford it or if legal aid were available to pay for it.

"According to a recent government report, judges estimate that cases involving litigants in person can take 50% longer than those represented by a legal professional."

A recent report by the Public Accounts Committee of MPs did say that "Judges have estimated that cases involving LIPs can take 50% longer". But we need to be cautious about that figure, which was described by the NAO as "anecdotal".

Judges' perception is that hearings in private family law cases when both litigants have no lawyer take around 50% longer. This isn't the same as saying that all cases take 50% longer to get through the court system.

The Ministry of Justice has published experimental statistics on the length of hearings before and after LASPO, which don't show any evidence that they take longer. These are based on estimated rather than actual hearing durations.

The statistics on the progress of cases through the system are more robust, and do show an increase in the average length of a private family law case. But that's the case whether or not there are lawyers involved.

While it makes intuitive sense that, as judges say, litigants in person take more court time and make cases go on longer, there isn't conclusive evidence of this at present.

"In the last year 1,500 people applied for exceptional [case] funding, but just 69 were successful."

Exceptional case funding was intended as a safety net to try to ensure that people who really need it still get legal assistance in non-criminal cases. It can provide civil legal aid in cases that mightn't otherwise qualify, but where denying it would be a breach of someone's human or EU law rights.

It's true that only 69 people were granted such assistance in 2013/14 out of 1,500 who applied. That's under 5%.

But the rate of successful applications has been increasing in every quarter since the scheme began. Overall, 10% of exceptional case funding applications up to the end of 2014 have been approved.

"The government say that our legal aid system remains one of the most generous in the world, with a £1.5 billion budget."

The outgoing government's ultimate aim is to reduce legal aid spending to £1.5 billion by 2018/19.

Comparisons between this and other countries' budgets are tricky.

Spending in England and Wales appears high in a Council of Europe report published at the end of 2014. It uses 2012 data, and so reflects the situation before many of the recent changes took effect. But at that time, only Norway (and Northern Ireland) spent more per head on legal aid.

That's not quite the full picture, though. European countries generally have a different legal system to the "adversarial" model of England and Wales. Here, judges expect parties to a case (through their lawyers) to present the best possible evidence for their side, and attack the opposing evidence. Continental systems give judges greater responsibility for finding and testing evidence.

That difference means that international comparisons between legal systems can be misleading.

In 2012, over 40% of the total judicial system spending in England and Wales went on legal aid. Only Norway devoted more of the system's resources to this particular element.

So whereas England and Wales spend more than anyone else in Europe on legal aid in isolation, relative to the size of the economy, the proportion spent on the justice system as a whole is slightly below average.

A better comparison would take in countries with a similar, adversarial legal system. The MoJ commissioned a report to look at some of these in 2009. It found that expenditure per head was "much higher" in England and Wales than in the likes of Australia, New Zealand and Canada, but also noted that looking at "legal aid expenditure in isolation" could be misleading.

As that research is now dated, we can't be sure whether the legal aid system "remains" comparatively more generous under the new rules.

"The Labour Party say they plan to review the cuts if they get into office."

Labour doesn't say much about legal aid in its manifesto, apart from a specific pledge to widen access for victims of domestic violence.

The Shadow Justice Secretary, Sadiq Khan, said in January that "I don't have a magic wand to wave. I can't commit to reverse the £600m cuts to legal aid". So while he told Panorama that he would "review" the changes, a return to previous levels of spending appears unlikely.

Mr. Khan has indicated that Labour would scrap a new system of criminal legal aid contracts—the tendering process for which closes on 5 May, two days before the general election—and review the 8.75% reduction in fees paid for criminal legal aid due this summer.