Employment rights

The Prime Minister says that her party’s plans for employment laws amount to the “greatest expansion in workers’ rights by any Conservative government in history”. We can’t speak to that—the Conservative record on employment laws goes back to at least 1800 and the Combination Acts—but here’s a brief rundown of what’s happened to employment rights since 2010.

It’s a mixed picture so far. Workers gain from things like shared parental leave and the creation of the statutory ‘National Living Wage’. But broadly speaking, the trend has been to put fewer restrictions on employers and more on trade unions.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

October 2011 - default retirement age abolished

Before October 2011 employers could retire an employee at 65 years old even if they didn’t want to retire.

The compulsory retirement age was removed in order to allow people to work for longer if they wished, as “people are living longer, healthier lives.”

Employers can still have their own compulsory retirement age if there is good reason for it—for example, for physically or mentally taxing jobs such as being a police officer or air traffic controller.

November 2011 - public sector pay cap extended

In the 2011 Autumn Statement George Osborne announced that public sector pay increases would continue to be frozen at 1% for the next two years, continuing the pay cap policy introduced by the previous Labour government in 2009. This commitment carried on throughout the Coalition government and in the 2015 Summer Budget the newly elected Conservative government committed to the cap staying in place until 2020.

The cap means that all workers employed by state-funded bodies (including the police, teachers and social workers) will not have their pay go up in line with inflation but have it limited to increasing by 1% per year.

Employees can still get pay rises of more than 1% as they move up pay levels with promotion.

The continuing pay cap will see the gap between public and private sector wages fall to its lowest for 20 years, according to the Institute for Fiscal Studies.

March 2012 - unfair dismissal rules changed

Employees have the right not to be unfairly dismissed. They used to be able to invoke it after one year’s continuous employment. That’s been raised to two years, benefitting employers.

The length of the qualifying period for unfair dismissal has been kicking around for years. According to research by the House of Commons Library, it started out in 1971 at two years; went to one year in 1974; to six months in 1975; back up to one year in 1979; back to two years in 1985; and down to one year again in 1999.

April 2013 - protection from third-party harassment scrapped

The Equality Act 2010 protects employees from various kinds of harassment by their employers.

That used to include harassment by a third party (so if you work in a shop, that would include harassment by a customer) where the employer knew about it but did nothing.

In scrapping the liability of employers for third-party harassment, the government argued that the rules weren’t “serving a practical purpose”, and weren’t “an appropriate or proportionate manner of dealing with the type of conduct that they are intended to cover”.

April 2013 - Enterprise and Regulatory Reform Act passed

This was the law that removed the obligation for employers to protect employees from third-party harassment, as mentioned above. It made other changes to employment protection too.

These included a requirement to consult ACAS (an independent body which advises on employment disputes) before taking certain cases to an employment tribunal. The law also allowed those tribunals to fine employers (as well as award compensation), and made changes to how tribunals operate, designed to reduce their workload.

The legislation also made important changes to whistleblowing law—summarised here.

July 2013 - cap placed on compensation for unfair dismissal

Compensation for unfair dismissal was limited to one year’s pay, with an overall limit of £74,200 (since increased to £80,541).

The amount you could get had previously had an overall upper limit but a separate limit relating to a year’s pay was a new feature. This reduced the potential compensation for many employees.

July 2013 - fees for using employment tribunals introduced

The Coalition government introduced these fees in order to, “relieve pressure on the taxpayer and encourage parties to think through whether disputes might be settled earlier and faster by other means.” Before that, there was no fee to take a case.

A person looking for compensation for, say, unpaid wages or unfair dismissal, now has to pay between £400 and £1,200 to have the case heard. Other fees might have to be paid, depending on the case, and to appeal a decision costs £1,600.

Tribunal judges can order the employer to pay the fees if a case is successful, although it’s not automatic. There’s also a ‘fee remission scheme’ to exempt people on low incomes. Around 60% of those applying are successful in getting their fees waived in part or in full, according to official statistics.

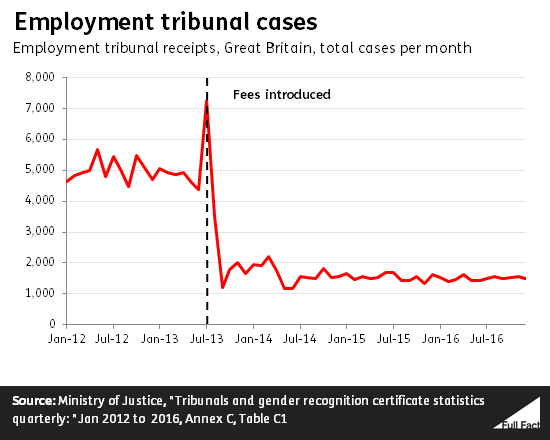

Nevertheless, the number of cases taken has fallen sharply since fees were introduced. The continuing low level of claims may also have been affected by a conciliation scheme introduced in May 2014, according to the House of Commons Library.

March 2014 - shared parental leave introduced

The right to 52 weeks’ maternity leave and 39 weeks’ maternity pay can now be split between parents. Blocks of leave that the mother hasn’t taken can be taken by either parent, rather than all in one go by one parent.

April 2014 - regulations to protect jobs when a business is sold

Transfer of Undertakings (Protection of Employment) regulations—known as TUPE—protect individual jobs when a business is sold or outsourced. The Coalition government said that it was updating the rules because they’d grown overly complex.

ACAS has a quick summary of the main changes. According to Reuters, they “ranged from major changes to the provisions on automatically unfair dismissal and post-transfer variations to terms and conditions, to more minor amendments to service provision changes, the time limit for providing employee liability information, and the employee consultation obligations owed by micro-businesses”.

May 2015 - exclusivity clauses in zero hours contracts banned

Exclusivity clauses forbid workers from working for another employer. They are seen as particularly unfair in zero hours contracts as they could stop workers from being able to take enough hours to earn enough to pay their living expenses.

The Small Business, Enterprise and Employment Act 2015 made such clauses unenforceable in zero hours contracts. Commentators criticised this as meaningless— there was no penalty for employees that withheld work if the worker ignored an exclusivity clause. So in January 2016 zero hours workers got the right not to be discriminated against by employers for failing to comply with an exclusivity clause.

April 2016 - National Living Wage created

The government has set a higher minimum wage for people aged over 25, under the official name of the National Living Wage. At the moment, it’s £7.50. The government wants it to rise to £9 an hour by 2020.

The National Living Wage is not be confused with the voluntary Living Wage that campaigners have been asking employers to pay for some years. It’s supposed to reflect the cost of “an acceptable standard of living” for people aged 18 or older; the recommended amount is £8.45 an hour (£9.75 in London).

May 2016 - Trade Union Act passed

The most significant bit of this law, according to the government itself, was the new requirement for a 50% turnout for strike ballots for a strike to have legal protection. Strikes in “important public services” need to be supported by 40% of workers eligible to vote—not just a majority of those who actually did vote.

Among other things, the law also made strike votes expire after six months; increased the notice to employers period from seven to 14 days; changed the rules on voting information; and made union political contributions opt-in rather than opt-out.

October 2016 - Taylor Review commissioned

The government asked former Labour advisor Matthew Taylor, Chief Executive of the Royal Society of the Arts, to investigate and report on the modern world of work. More specifically, the brief was to “consider how employment practices need to change in order to keep pace with modern business models”—in other words, how best to regulate the ‘gig economy’.

The report is reportedly due out in summer 2017.