AV Referendum: did AV cause turnout to fall in Australian elections?

"[Australia] even had to make voting compulsory because so many were put off by the prospect of AV."

David Gower, The Sun, 14 April 2011

The experience of Australia's electorate with AV, as one of the four in the world that uses the voting system for national elections, has provided a focus for both 'Yes' and 'No' camps ahead of next month's referendum.

Today a man who knows a thing or two about Australians, former England cricket captain David Gower, came out to bat for No2AV, claiming that his erstwhile Ashes opponents had to introduce compulsory voting because Australians were so disenchanted by the Alternative Vote.

This is at odds with the claims of some advocates of a change in the electoral system, who have suggested that AV would "increase voter turnout."

So is Mr Gower putting a spin on the Australian example?

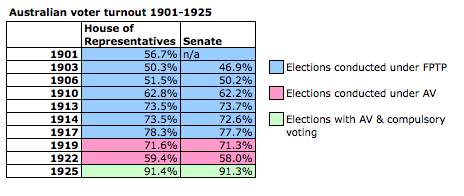

A look at Australian voter turnout figures in the two elections conducted on a voluntary basis with preferential voting would suggest that Mr Gower has a point. The 1917 Federal election, which was the last to be held under First Past The Post, saw a 77.7 per cent turnout for the senate ballot. After the switch was made to a form of AV in 1918, turnout fell slightly to 71.3 per cent in 1919, and more significantly to 58 per cent in 1922.

Similarly the link between declining turnouts and the introduction of compulsory voting is a fair one. The Australian Electoral Commission has noted that: "The significant impetus for compulsory voting at federal elections appears to have been a decline in turnout from more than 71 per cent at the 1919 election to less than 60 per cent at the 1922 election."

But was this fall in turnout a consequence of the introduction of preferential voting, or is it mere coincidence?

The first point worth making is that in the first four Commonwealth elections held in Australia between 1901 and 1910 under FPTP saw average turnout of 54.4 per cent, which then jumped sharply in the years around World War I, where average turnout was around 74 per cent between 1913 and 1919. Which of these makes the fairer benchmark for turnout, given the exceptional political circumstances which encompass the creation of Australia as a sovereign nation in 1901 and WWI between 1914 and 1918, is therefore unclear.

Certainly there is evidence to suggest that the fall in turnout in 1922 had more to do with voter apathy in a period of less political turmoil than the preceding years. Prime Minister of the time Billy Hughes reportedly told the Sydney Morning Herald on 22 December 1922 that "people are too well off and contented to worry about elections."

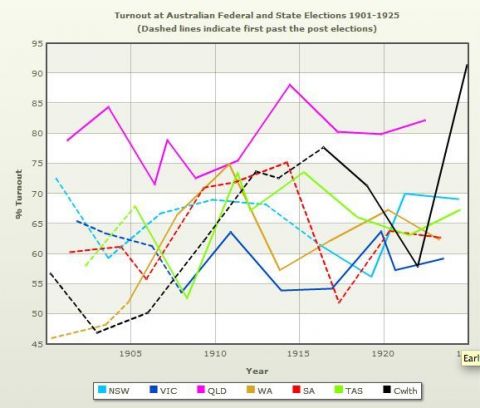

Furthermore, preferential voting was introduced for Australian state elections in many places before it was introduced on a national level in 1918, and had no clear effect on voter turnout. Analysis by Australian academic Colin Hughes for the Australian Journal of Political Science, reproduced by the Australian Broadcasting Corporation's election commentator Antony Green showed that in some states, such as Victoria and Western Australia, turnout rose immediately after the introduction of preferential voting, but in others, such as New South Wales and Tasmania, turnout dipped. It also highlights that the biggest fall in turnout in the first quarter of the twentieth century was in Southern Australia, which kept FPTP until 1929.

(For the graph above, a dashed line indicates elections under FPTP, whilst a solid line indicates elections conducted under preferential voting.)

This more nuanced picture is supported by evidence from other international adopters of AV, such as certain Canadian provinces between the 1920s and 1950s. Studies of these elections found that there was little or no evidence that either the introduction or abolition of AV had any direct impact upon turnout.

So whilst turnout did fall after Australia adopted AV in 1918, it is difficult to establish a sound causal link between the two. Whilst it is difficult to disentangle the change in the voting system from other contemporary social phenomena, what evidence there is gives a mixed picture, suggesting that any impact is limited.

It is also true that the voting system adopted by Australia in 1918 is different to that which is being put before UK voters on May 5th. Whilst our antipodean cousins were required to use all their voting preferences in the 1919 and 1922 elections if their ballot were to be considered valid (known as "full preferential voting"), in the UK AV would take the form of "optional" preferential voting, under which voters are free to express a preference for as many or as few candidates as they choose. This makes it even more difficult to apply the lessons learned in Australia, such as they are, to the UK.

As far as David Gower is concerned therefore, this particular claim might be best left in the pavilion.