BBC Question Time: Recap and Factcheck

Topics covered included Universal Credit, the potential for another independence referendum, the Scottish education system, the usual smattering of Brexit, and whether it’s quicker to get a home delivery of pizza or cocaine.

On the panel this week were the SNP’s Mike Russell, former Scottish Labour leader Kezia Dugdale MSP, and Conservative MP for Aberdeen South Ross Thomson. Also appearing was editor of The Spectator, Fraser Nelson, and veteran crime writer Val McDermid.

The first factcheck of the night came hours before the programme even began, when McDermid corrected the Question Time Twitter account on how many novels she’s written—it’s 32, by the way, not 27.

Your fact from the location this week is a good’un. Edinburgh is home to Sir Nils Olav, whose knighthood was approved by the King of Norway in 2008.

Sir Nils Olav is a penguin at Edinburgh zoo.

Anyway, onto the show.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Question 1: Universal Credit

The first question of the night came from an audience member, who asked why the UK government was going ahead with the rollout of Universal Credit when the new system had been criticised by people from all sides of the political spectrum.

Two former prime ministers—Sir John Major and Gordon Brown—this week warned that the government could face backlash akin to that against Margaret Thatcher’s poll tax.

Kezia Dugdale claimed that “As I understand it, and Esther McVey, the Secretary of State has admitted herself, half of all lone parent families are going to lose over £2000 a year and two thirds of working families [are too].”

This was reported by the Times earlier this week. The paper said that the Work and Pensions Secretary had “confirmed privately to colleagues” that “half of lone parents and about two thirds of working-age couples with children would lose the equivalent of £2,400 a year.”

The Department for Work and Pensions did not comment on the Times’ report. We’ve written more about what changes to Universal Credit could mean for lone parents here.

We’re aiming to look at this in more depth soon.

Ross Thomson MP outlined why he thought Universal Credit was important: “When Universal Credit is rolled out fully, 200,000 more people will be in work”.

This is what the government estimates will be the case by 2024/25. It’s compared to what the government expects would have happened if Universal Credit had never been introduced.

There are big doubts over this estimate. For a start, there’s no way for Mr Thomson or the government to know if this will ever be true. According to the National Audit Office (NAO), “The Department will never be able to measure whether Universal Credit actually leads to 200,000 more people in work, because it cannot isolate the effect of Universal Credit from other economic factors in increasing employment.”

The NAO has also raised concerns that the figure is based on early evaluations which focus on claimants with relatively simple needs, so we don’t know if the evidence already gathered will be representative of Universal Credit’s impact on future claimants. We’ve got more on this in our factcheck.

Question 2: Brexit and a second Scottish referendum

The panellists and the audience then moved onto a discussion of how Scotland voted on Brexit and the possibility of a second independence referendum.

Mike Russell said “The people of Scotland voted against Brexit.” Ross Thomson then said “I voted to leave the European Union alongside a million other Scots.”

Both are correct. Just under 1.7 million Scots—62% of those voting—voted in favour of Remain during the EU Referendum of 2016. Just over 1 million—38%—voted in favour of Leave.

It all got a bit personal when Ross Thomson said the SNP were the “world’s worst losers”. Ouch.

After some discussion of the viability of a second Scottish independence referendum, an audience member asked the panel “What do you say about the new poll that came out today that showed that over 80% of English Brexiteers would be happy to pay the price of a second Scottish independence referendum and then leaving to have Brexit?”

This comes from polling done by YouGov and LucidTalk, on behalf of the Centre on Constitutional Change based at the University of Edinburgh.

The poll effectively asked respondents to decide whether or not they thought Scotland voting to leave the UK in a second independence referendum would be worth it for the sake of achieving Brexit. The question was as follows:

“Some have suggested that leaving the European Union might present challenges to the UK. One of these includes a second independence referendum in which a majority of Scots vote to leave the UK. If this happens would you say that:

- It was worth it to take back control (or)

- Leaving the EU was not worth risking a Yes vote in a second referendum”

Among respondents from England who voted to leave in the 2016 EU referendum, 88% answered that Scotland leaving the UK was worth it to “take back control”. A similar proportion of leave voters agreed in Northern Ireland (88%) and Wales (86%). It was slightly lower in Scotland (71%). Among all respondents (including leave voters, remain voters and those who did not vote), 52% in England agreed that Scotland leaving was worth it, 51% agreed in Wales, 46% agreed in Northern Ireland, and 43% agreed in Scotland.

The research was conducted between 30 May and 6 June this year, so it doesn’t give quite the latest picture. We don’t know if events in the intervening period—the Chequers agreement, the Salzburg summit, debates about what the final deal will look like—will have changed people’s attitudes in any way.

Financial sector jobs in Edinburgh

Kezia Dugdale said: “The first thing that will go when we leave the EU are the jobs, which support so many Scots, not least in this city, where 25% of people work in the financial sector.” We’re looking into this claim.

Question 3: Will Theresa May survive until Christmas?

A member of the audience asked whether, with the DUP reportedly threatening to vote against the budget, Theresa May would still be Prime Minister by Christmas.

Fraser Nelson said if Theresa May couldn’t get her budget through, it wouldn’t bring down the government, but might well trigger a leadership crisis. We’ve written more about how leadership contests works in the Conservative party here.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Ross Thomson said he didn’t think the Prime Minister would go.

“I support the Prime Minister because I believe she is the best person to deliver the Brexit deal,” he said.

“That's why I have been critical of Chequers,” he said, “because I want to help her to have the best possible deal to get through.”

He also mentioned the potential of having some kind of Canada-style deal, which we’ve covered before.

Question 4: Drugs and Scotland

Claims went flying during this part of the show—after an audience member asked what the panel would do to combat Scottish drug deaths.

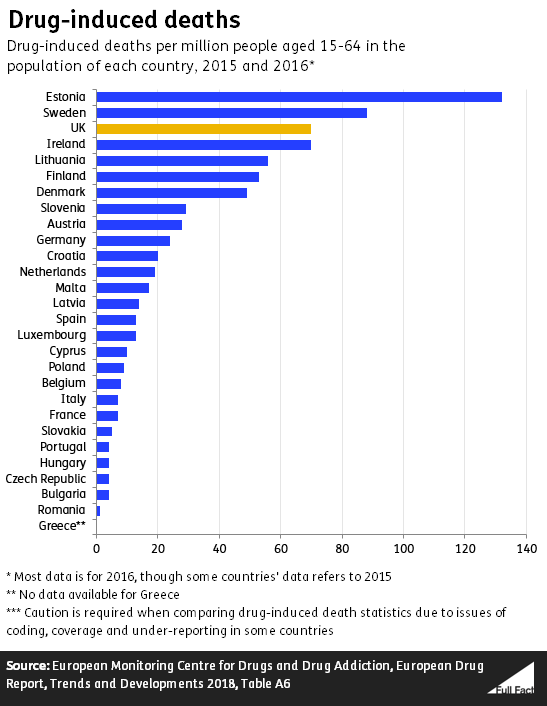

Before going to the panellists for their reaction to the question, Dimbleby provided some figures on the issue. “The figures incidentally are nearly 1,000 drug-related deaths in Scotland last year, and 3,700 in England and Wales, and the UK [has] the highest death rate in the EU from drugs.”

His figures on the number of deaths are roughly correct for those registered in 2017. Estonia had the highest rate of drug-related deaths in the EU, per million people aged 15 to 64 in each country, based on research using data from 2015 and 2016. The UK placed joint-fourth alongside Ireland. The National Records of Scotland calculated that if Scotland was added to this league table, it would have the highest drug-related death rate in the EU. We’ve written about this in more detail here.

Kezia Dugdale spoke about proposals for safe injection facilities for addicts, which she said the Home Office had blocked.

The show took an unexpected turn, when Ross Thomson said “What is deeply worrying about what is happening in Scotland [is] that it is quicker online, using an app, to order cocaine to your house than it is a pizza. If you are in Glasgow you can get that delivered to your door quicker than a Domino's.”

Surprisingly, we were actually able to factcheck this. The 2018 Global Drugs Survey asked 15,000 cocaine users around the world whether they could get a) cocaine and b) a pizza delivered in under 30 minutes. Around the world, 30% of users said they could get cocaine delivered in under 30 minutes, while only 17% said they could get a pizza in that time. (It’s worth noting that the GDS is an opt-in online survey, so will not be a representative sample of all drug users, although academics involved with the survey have done some work that suggests it is broadly representative.)

Looking specifically at Scotland, 37% of cocaine users in the survey said they could get cocaine delivered within 30 minutes, which is above the global average (the figure for England is marginally lower, while Brazil, the Netherlands, Denmark and Colombia are higher). And Scotland leads the world for same-day delivery of cocaine, with 86% of respondents saying they could get it delivered on the same day. But the GDS report doesn’t break down pizza delivery times among their sample by country, so we can’t rule out the possibility that while Scotland—a nation already noted for its innovation in the takeaway fast-food market—does have relatively wide availability of rapid cocaine delivery, they might be even faster at getting you a pizza.

Question 5: Should Scotland be testing five-year-olds?

The final audience question centred around the Scottish National Standardised Assessments—and whether the age they’re first taken, in school year P1 (which starts when children are aged 4 or 5), is appropriate.

As the programme drew to a close, David Dimbleby decided to muddy his paws and start making some claims of his own: stating that Scotland had its “Worst ever results in the PISA international tests in 2016”.

To which Russell responded: “on a level, broadly, with Wales, Northern Ireland, and England. If you knew about Pisa in detail you would know that what has happened in Pisa over many years is that that testing has moved into a way that benefits some countries and not others.”

The Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) is a survey run by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) which tests the skills and knowledge of 15 year olds in different countries. It specifically seeks to test children’s “functional ability”: so how well they can use their science, maths, and reading skills in “real life” situations.

In the latest results, for 2015, Scotland generally performed worse than England and Northern Ireland, but better than Wales.

Scotland was comparable to the OECD average performance in each of reading, maths, and science. England was above average in science and reading, and Northern Ireland was above average in science (both were average in all other areas), while Wales was below average in all three.

Scotland’s performance dropped in each of the three subjects, compared to its previous set of results from 2012. Scotland had previously been above the OECD average in reading (from 2009 to 2012) and science (2006 to 2012).

The findings from PISA league tables need to be interpreted with some caution. We’ve looked in the past and what they do and don’t tell us about a country’s performance.

And with that, David Dimbleby rounded up proceedings.

“We get told off if we don’t finish in an hour, that is the way of the world.”

We can’t argue with that.