BBC Question Time: Recap and Factcheck

If there’s one TV debate you can always rely on happening, it’s BBC Question Time. This week’s came from Bishop’s Stortford in Hertfordshire.

The topics covered this week were several questions around the government’s Brexit withdrawal agreement, climate change and the police tactic of knocking suspected criminals off mopeds during a pursuit.

On the panel this week were Conservative MP and Secretary of State for Housing, Communities and Local Government James Brokenshire, Labour’s shadow Attorney General Shami Chakrabarti, Leader of the Scottish National Party group in Westminster Ian Blackford MP, journalist Charles Moore, and Jill Rutter from the Institute for Government.

And before we go any further:

Obscure fact about Bishop’s Stortford tangentially related to politics: In 2011 Bishops Stortford council voted to no longer support the town being twinned with towns in France and Germany, after 46 years of being twinned. The Bishops Stortford Town Twinning Association continues to argue that the council should reverse its decision.

Honesty in public debate matters

You can help us take action – and get our regular free email

Questions 1, 2 and 3: Brexit

The show began with the dominant political story of this week: the debate that’s been happening in parliament over the government’s withdrawal agreement, which MPs are currently set to vote on next Tuesday.

The panel were asked if the deal will be rejected, and what would happen next if it were. They were also asked whether Labour and other opposition MPs should stop pushing for another deal and back the Prime Minister, and if the PM herself should resign if she loses Tuesday’s vote.

There was some talk of the government’s defeats in the House of Commons this week after its refusal to release the full legal advice it received on the withdrawal agreement, and on MPs’ ability to force the government to change course on Brexit. We explained what all these votes meant earlier this week.

The panellists were soon in disagreement over whether the “backstop” part of the withdrawal agreement was temporary or permanent.

To recap briefly: the Irish backstop is an insurance policy under the withdrawal agreement to avoid a hard border between Northern Ireland and Ireland. If the withdrawal agreement is approved by parliament, and a deal with the EU isn’t negotiated before the end of the transition period in December 2020 (or later if it’s extended), we will go into the backstop.

James Brokenshire insisted: “If you actually look at some of the legal base under which this has been created, that underlines the temporary nature of what it is … the agreement says that it is temporary”. But Ian Blackford disagreed, claiming “we know from the legal advice where it states the following: international protocol would endure indefinitely”.

Both the EU and UK say the Irish backstop is intended to be temporary, and it would be if an alternative agreement was reached to take its place. But the government’s legal advice says if this doesn’t happen, it would endure indefinitely. We’ve talked more about this here.

Shami Chakrabarti then contrasted this situation with Labour’s own policy, saying: “[Labour] wouldn’t have all this problem with the backstop etc because we want the whole of the United Kingdom to be in a permanent customs union with the EU.”

Ms Chakrabarti seems to be suggesting that Labour’s proposed future trade agreement with the EU would guarantee no hard border between Northern Ireland and the Republic of Ireland. The implication is that Labour’s proposal would remove the need for the Irish backstop trade arrangements (which are designed to avoid a hard border as a position of last resort).

Labour’s proposals may avoid a hard border in Ireland, but it seems extremely unlikely that the EU would accept those proposals alongside everything else Labour wants from Brexit. For example Labour wants the UK to have a say in the EU’s trade deals post-Brexit, which appears to fall foul of the EU’s red lines.

We’ve written more about this here.

After ten minutes of intense legalistic debate, David Dimbleby lamented: “I hate this word backstop. I wish we could call it a safety net or something different”. Jill Rutter then unexpectedly offered him some solace straight from her German dictionary “The Germans actually call it a safety net, that’s what the German word is for it”.

“Safety net” (or Sicherheitsnetz) does seem to be the typical German word for referring to the kind of legal mechanism that the Irish backstop is, although they also use the term “backstop” (in English). For example, back in August the German version of an article by Michel Barnier used both terms together: “brauchen wir ein Sicherheitsnetz, eine Art „Backstop“ im Austrittsabkommen”. In case your German is a tad rusty, that roughly translates as “we need a safety net, a kind of “Backstop” in the withdrawal agreement.”

So ubiquitous has the Irish backstop become in the Brexit negotiations, that the German press seem to regularly use the English “backstop”, in a more colloquial sense, when referring to that aspect of Brexit negotiations. (The actual German word for backstop, “rücklaufsperre”, does not get much love.)

Question 4: Climate change

In a break from Brexit, the show moved on to discuss this week’s United Nations talks on climate change, where Sir David Attenborough said climate change is our greatest threat in thousands of years.

In response to that, one audience member asked the panel: “why aren’t politicians doing enough?”

Jill Rutter, who used to work at the Department for Environment, Food and Rural Affairs, said she thought politicians didn’t always act because of concerns about public opinion, and pointed to the violence seen recently across France, initially in response to increases to fuel duties there.

She went on to say “Our government’s frozen fuel duty since 2010. That’s actually lost revenues of about £6-7 billion”.

This is too low—the latest estimate shows the cost is higher than that.

Fuel duties have been frozen in cash terms (or before inflation is accounted for) since April 2011. If these duties hadn’t been frozen, and had increased in line with inflation instead, the Institute for Fiscal Studies estimates that the government would have collected around £9 billion more in taxes by the end of 2018/19 than it actually will (it estimated around £6 billion the previous year).

The government announced in the October Budget that it planned to freeze them again in April 2019.

On the UK’s own record at cutting carbon emissions, James Brokenshire correctly said: “we have the strongest record in the G7, we’re actually getting economic growth but cutting our carbon emissions.”

From 1992 to 2014 UK GDP per person grew by 45% in real terms and carbon dioxide emissions per person fell by 33%, according to a report by the independent Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit.

More recent data from the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy shows that between 1990 and 2017 carbon dioxide emissions fell 38%, while greenhouse gas emissions in total fell 43%.

In 2008 parliament passed legislation committing the government to reduce carbon emissions 80% by 2050, compared to the 1990 baseline.

Mr Blackford added: “The Scottish government has led the way across Western Europe. We have cut our emissions by almost half since 1990 and we have a target by 2050 of being carbon neutral”.

That’s also correct. The Scottish government is trying to pass legislation to increase its carbon reduction target from 80% to 90% by 2050, and add a separate commitment to reduce carbon emissions by 100% “as soon as possible.”

Scotland has reduced greenhouse gas emissions faster than the rest of the UK (using a measure that doesn’t include any emissions from ‘offshore operations’). Between 1990 and 2016 Scotland’s carbon dioxide emissions fell by 52% and greenhouse gas emissions fell by 49%.

That ranks second among western EU countries and fifth among all EU countries.

Question 5: Moped crime

To round off the show, there was a short question asking whether the panel agreed with the police tactic of knocking suspected moped criminals off their vehicles during a pursuit.

Our host began: “tactical contact, they call it, and it has been used apparently 63 times since October last year.”

Tactical contact is “when a suitably trained police driver deliberately makes contact (with someone they are pursuing) using their vehicle”. The Metropolitan Police told us the tactic had been used more than 60 times this year by the “Operation Venice” team tackling moped crime, though it wouldn’t confirm the exact number of 63 mentioned by multiple media reports. They also recently released a video showing police using the tactic.

This method made headlines recently, after it was reported that a police officer has been put under criminal investigation for using the tactic last year to knock a 17-year old off their moped. The teenager wasn’t wearing a helmet and was admitted to hospital with “serious head injuries” but has since been discharged. This prompted the Independent Office for Police Conduct to launch an investigation.

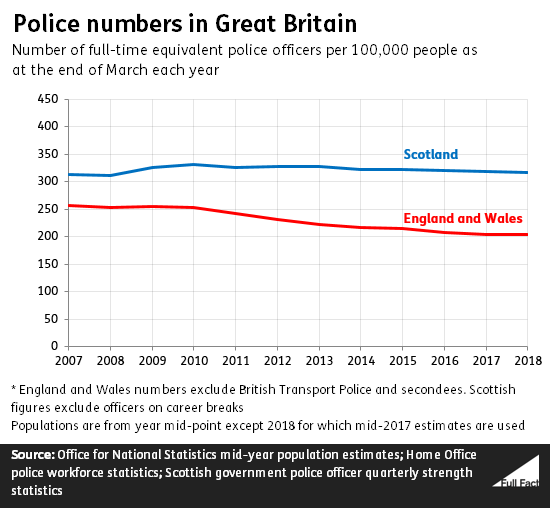

Ian Blackford went on to argue that the problem was under-resourced policing. He said: “Police numbers in England and Wales have gone down quite substantially while in Scotland they have actually increased.”

Since the SNP came to power in Scotland in 2007, the number of full-time equivalent police officers has increased by 6%, from over 16,000 to just over 17,000. However most of that increase came between 2007 and 2009, and since then police numbers have been fairly flat.

The number of full-time equivalent police officers in England and Wales (excluding British Transport Police and officers seconded out) decreased by 14% between March 2010 and March 2018. That’s from around 144,000 to 122,000. We’ve written more about this here.

Currently there are around 320 police officers for every 100,000 people in Scotland and 210 for every 100,000 people in England and Wales.

And so ended the programme. Today the BBC confirmed Fiona Bruce will take over as Question Time presenter from David Dimbleby, who has one show left next week. We’ll see you then.