Ed Miliband's energy price freeze: what's it all about?

It all happened in a few seconds, but the furore surrounding it looks set to go on for days. Ed Miliband this week unveiled what is likely to be one of the most eye-catching policy pledges of Labour's 2015 manifesto:

"If we win the election 2015 the next Labour government will freeze gas and electricity prices until the start of 2017."

It's been met with a furious reaction from the big energy companies. Centrica (which trades as British Gas) warned that price controls against a background of rising wholesale costs could force it out of operations in the UK. Npower said that price fixes could squeeze out investment needed to renew the UK's energy infrastructure.

But the promise of fixed energy bills may still play well with consumers. Even so, the announcement prompted many unanswered questions.

The price of energy

The first port of call in formulating a policy is (ideally) defining what the problem is. For Labour, it's the energy prices faced by consumers. Energy regulator Ofgem estimates the average yearly retail bill for dual fuel (gas and electricity) is currently £1,315. That's assuming someone is on a standard tariff, so obviously there'll be a range of bills around this average.

Back in May 2010 - at the time of the election - the same bill was estimated at £1,105, and was less than £1,000 before 2009.

Ofgem's own figures show what factors are playing their part in this:

And this isn't just a recent trend. The prices of gas and electricity have been rising in real terms for the past decade. As we've discussed before however, much of the rise in energy bills for consumers can be attributed to rising wholesale market prices for gas and electricity.

As for Labour's own figures, they've estimated the policy would save average households £120 a year. We've asked Labour for their sources, but they haven't yet been forthcoming.

We ran our own calculation, assuming that the average yearly rise in consumers' fuel bills seen since 2009 (roughly 5%) plays out till 2017, versus a scenario in which prices are frozen in 2015. It varies a lot on which time period you use to take the average rise, but our estimates suggested the difference to consumers' bills would be in the region of £130 a year - not far off Labour's estimate.

But the assumptions involved here are still quite stretched - bills won't necessarily continue to rise at the rate they've done recently. There are too many unpredictable variables - variations in the market costs of gas and electricity and even the behaviour of energy companies with the knowledge that their prices might be frozen. So it's difficult to be sure of any estimate surrounding consumers' savings.

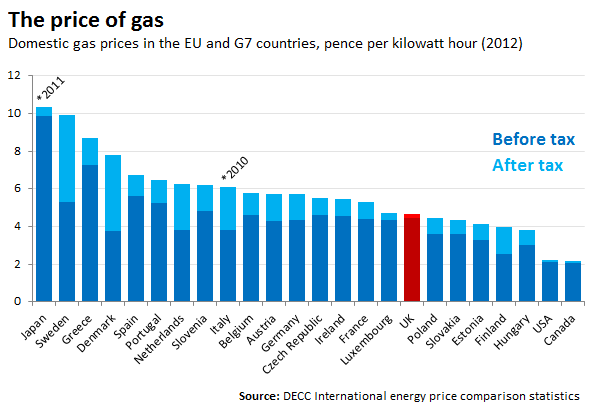

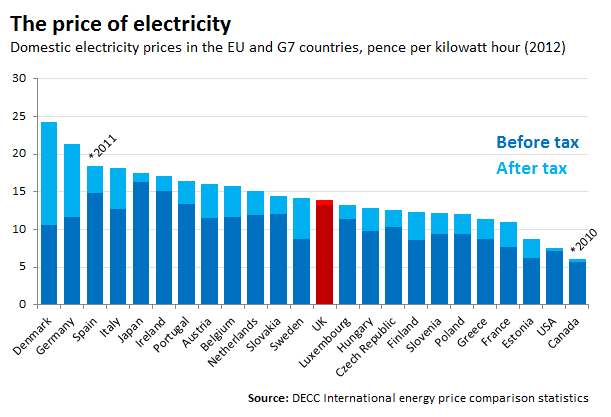

Compared to everyone else

Compared to the rest of the EU, UK energy prices are relatively cheap. Energy bill survey data from energy.eu shows the UK is currently the third cheapest EU country for gas (for which there's data) and average in the EU for electricity.

Figures are also readily available for the USA, Canada and Japan via the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC). They publish comparative figures covering 2012:

It's interesting that, while consumers in the UK do face relatively cheap prices compared to their neighbours in most other large economies, a lot of this is thanks to the tax system. Without factoring taxes in, the UK's energy prices are actually relatively expensive. It's the relatively generous tax regime that slides us down the league table.

Profits for energy firms

For some, increasing profits are evidence that energy firms are placing a disproportionate burden upon customers. For others, profits are a means of generating investment for improving the nation's energy infrastructure.

News outlets and commentators often mention profits for energy companies alongside prices for consumers in the same breath. But these need to be handled with care, as figures for the overall profits and costs of energy companies aren't readily available.

Instead, Ofgem's electricity and gas market indicators are quoted. In September 2013, it's estimated that energy companies make a margin of £65 - or 4.9% - on each energy bill (the portion that doesn't go towards directly supplying the energy to the customer). Margins have been rising since 2006.

But this isn't the same as profits, because companies will have other arms of their businesss with associated operating costs and profits. Ofgem provide links to these in one place.

A recipe for blackouts?

Energy Secretary Ed Davey hit out at the plans, claiming it risked the "lights going out", although some have also claimed that this kind of respopnse is little more than 'scaremongering'.

It's an impossible task to factcheck the future, but some have justified their concerns by appealing to the past. California's energy blackouts from the early noughties have been cited as an example of what goes wrong when prices are fixed.

The problem is that attributing California's energy supply woes solely to fixed pricing isn't that clear cut. One study from the Public Policy Insititute of California analysed the factors which may have played a part in causing the widespread and persistent blackouts faced by Californians.

But they, along with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission, don't point to a single-cause of the problem. They mention general factors surrounding peculiarities in California's market structure - including "regulatory missteps" - but don't lay all the blame on price fixing.

So, at the very least, the examples being cited aren't necessarily clear-cut cases of the consequences of price freezing policies. It's quite possible that several factors specific to California's market caused California's problem, and the state's suitability as a warning of the dangers of this policy to the UK market is an open question.

This article was updated on 26 September to add in Ofgem's breakdown of what contributes to an average energy bill.