The future of North Sea oil and gas

- Revenue from the North Sea oil and gas reserves would be an important source of income for an independent Scotland, if it wanted to continue spending at the current level.

- How these resources would be divided up in the event of independence would have to be negotiated with the UK government. A geographical share (rather than a share on the basis of population size) would be the most beneficial to Scotland.

- The amount of money Scotland could expect from future receipts is difficult to predict since prices can fluctuate massively year on year. Experts predict a long term decline in North Sea revenue as resources are expected to run out.

Scotland currently enjoys a higher level of spending per person than the rest of the UK. This happens regardless of the size of revenues from the North Sea - which go straight into the collective UK budget.

But if Scotland becomes independent, the size of what become its own North Sea revenues will have a big effect on whether it can keep up these spending levels. The size will depend on the share of resources allocated to Scotland and how fruitful offshore production continues to be in the future.

If the oil and gas fields (and so the revenues) had been divided geographically between Scotland and the rest of the UK over recent years, the Institute for Fiscal Studies (IFS) says Scotland's higher level of spending would have been roughly accounted for by additional revenues from the North Sea.

Revenues depend on how resources from the North Sea are divided

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="329"]

Having a geographical share, based on the "median line" (the fishing boundary between Scotland and the rest of the UK) would be the most beneficial decision for Scotland - as opposed to a share based on population size.

Based on their estimates of the geographical share, academics from the University of Aberdeen estimated oil production in Scottish waters represented about 96% of total North Sea production in 2012, while Scottish gas production represented about 47%.

This share can change in any given year - while the number of fields in 'Scottish waters' may not change, the amount of oil or gas extracted from them (production level) or the amount of profit they generate could change and so affect the overall Scottish share of total production or revenues.

Oil fields are relatively more profitable than gas. So given that Scottish waters are thought to generate the majority of the North Sea oil, but only half of the North Sea gas, Scotland still ends up with an estimated majority share of UK revenues generated from the North Sea.

There is some divergence between estimates though: in the five year period from 2008/09, Scottish government statistics estimate Scotland's share of North Sea resources generated between 84% and 95% of total UK oil and gas revenues each year, while HMRC's experimental statistics found it was between 73% and 88%.

The Centre for Public Policy for Regions has said the reason for the slight differences is because of different assumptions on costs in individual fields and tax reductions given to companies by the government. Both estimates use the same boundary line and production data.

A population share of revenues would give Scotland just 8%. Taking the Scottish government's statistics, this would have resulted in receipts to Scotland of £550 million in 2012/13, while its estimate of the geographical share for the same year (84%) find Scotland would have received £5.6 billion.

The UK government has said it would negotiate the share if Scotland votes yes. Its projections of Scotland's possible financial future under independence assume Scotland ends up with a geographical share.

Oil prices are extremely volatile

"Oil prices seem historically to have followed something closer to a random walk rather than oscillating around a well-defined trend". Institute for Fiscal Studies.

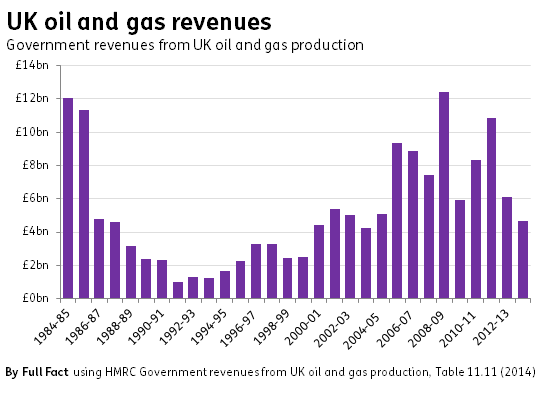

Recent years have been particularly unpredictable for the taxman when it comes to oil and gas: the annual amount raised more than halved between 2008/09 and 2009/10, before almost doubling again over the subsequent two years.

Since 2002, oil and gas revenues have on average increased or decreased by nearly 35% each year, according to the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR). In contrast, income tax receipts go up or down by an average of just 5% each year.

Part of this volatility has been driven by sharp fluctuations in the wholesale cost of oil and gas.

Future revenues will depend on continued changes to the price of oil and gas as well as how much gets extracted, how much companies choose to invest in the area, and the costs associated with expanding production (such as finding more oil).

The size of the swings Scotland would have to absorb would be proportionate to the share of the revenues it eventually received in any post-referendum settlement.

The next five years could see revenues fall by £100 million or increase by £2.4 billion

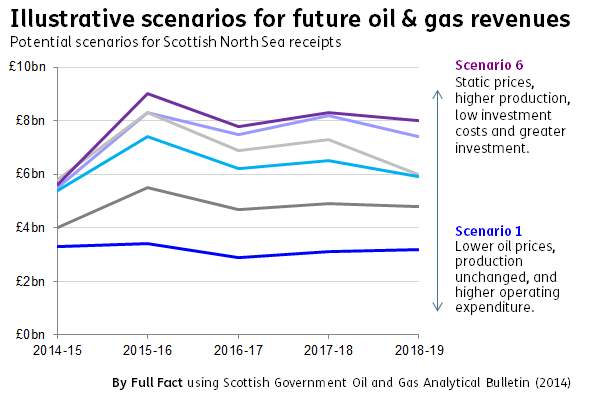

The Scottish government has forecast a range of possible outcomes for Scottish revenue from the North Sea over the five year period to 2018/19, based on Scotland having a geographical share of revenues. Its most rewarding projection estimates revenues will increase by £2.4 billion - predicting high prices and production levels, and lower costs for exploration, appraisal and investment.

Its least rewarding scenario finds Scottish revenues would fall by £100 million - based on revenues predicted by the OBR for UK oil and gas over the same five years. The OBR's forecasts don't strictly refer just to North Sea production - it incorporates all UK oil and gas fields, but the North Sea accounts for the vast majority of these.

The OBR's forecasts actually cover a six year period, starting from 2013/14, rather than 2014/15 like the Scottish government's. Over this longer time frame it shows its predictions of the losses could be far greater - with a possible £1 billion fall in UK wide revenues from 2013/14 to 2014/15, before the Scottish government's projection period begins.

Although the OBR's forecasts appear to be the most 'pessimistic', previous OBR forecasts have ended up being too optimistic. For example, in 2010/11 and 2011/12 receipts grew by less than expected by the OBR and, in 2012/13 and 2013/14, the money coming in was less than half the OBR's predictions. So all forecasts are hugely sensitive and subject to change.

Reserves may start to run out over the next 25-35 years

The OBR has said that all its scenarios to 2040/41 predict a long-term decline in revenues from the North Sea as the resources diminish.

Experts disagree on how much oil and gas is left in the area. Oil and Gas UK, the industry body, has predicted the industry will remain active beyond 2050 and that amount of unextracted oil and gas would fill the equivalent of an estimated 15 to 24 billion barrels of oil - while the UK government has made a lower estimate of 11 to 21 billion barrels.

Business organisation N-56 has suggested the remaining reserves could be bolstered by extraction of shale oil and gas, predicting this could add an additional 21 billion barrels. Like many of the predictions, the claim has been reportedly criticised by some well-known oil experts and welcomed by others.

Estimates of the value of the remaining reserves are contentious too. On the basis of there being the equivalent of 24 billion barrels of oil left, the Scottish government has said the remaining resources could have a wholesale value of up to £1,500 billion (in 2012 prices). The UK government has criticised this estimate for using the most optimistic prediction of remaining resources, as well as its use of a wholesale value since it doesn't include the cost of extraction - which alone it estimates as more than £1,000 billion (in today's prices). Instead, it estimates the value of the remaining reserves is 12 times lower, at £120 billion (as of December 2011).

Extracting these resources will also depend on future investment - the Wood Review of the the UK oil and gas industry concluded that UK production is:

"facing stiff and growing competition from many international offshore regions and we need to step up our game to attract more investment".

Reserve fund could be possible, but not at the same scale as Norway's

Scottish First Minister Alex Salmond has disputed (£) the idea that the size of the swings in oil and gas tax receipts would be crucial to an independent Scotland's financial future, arguing that the country could establish a reserve fund to smooth out the volatility in the market - as exists in Norway. There's potential for both a short term Stabilisation Fund - to smooth out volatility - and a longer term Savings Fund.

But the Centre for Public Policy for Regions (CPPR) has said that while a Savings Fund could be possible if spending was cut:

"the annual input into such a fund is likely to be relatively small and not on anything like the scale seen in Norway".

The IFS has also said the option of saving oil revenues, by not counting them in short-term budgets and building up a fund (or being used to lower debt) "does not seem to be an option in current fiscal circumstances".